How Chinese artist Xu Bing made an entire film out of surveillance camera footage

Dragonfly Eyes, ostensibly a love story told through publicly accessible footage compiled from surveillance cameras, is yet another example of Xu having to wait for reality to catch up with his initial concept

Xu Bing has visited Hong Kong many times as one of China’s leading conceptual artists of the past few decades. Here on this occasion for the 42nd Hong Kong International Film Festival, however, it is the first time he has come to the city to promote a movie rather than install an exhibition.

“It’s surely more convenient this way,” says Xu with a smile. “But there is little convenience about the way we made this movie.”

Two Chinese movies at Locarno Film Festival offer subtle commentary on the state of the nation

Since its world premiere at the Locarno Festival last August, Dragonfly Eyes, Xu’s debut feature, has been touring an international film festival circuit that was previously alien territory for the first-time director who is much better known as an artist than a filmmaker.

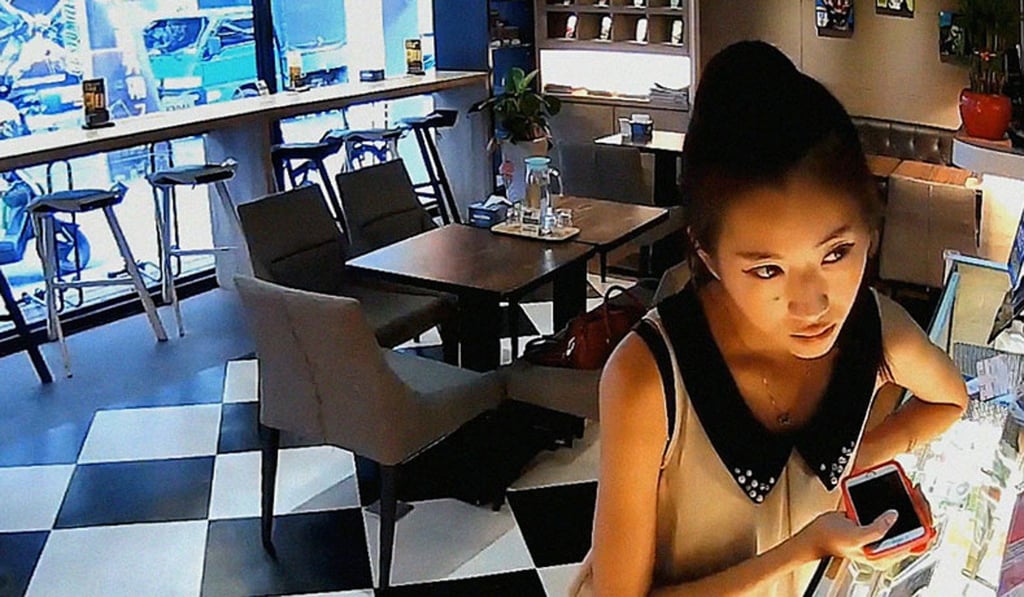

The idea for Dragonfly Eyes, which ostensibly tells a love story between a man and a woman through images compiled from publicly accessible surveillance camera footage, came about when Xu saw some security camera recordings on television back in 2013.

“I had the feeling then that these images hold a special kind of attraction to me,” he recalls. “They are ultra-realistic in the way they manage to reflect the relaxed state of people going about their daily life. I thought it would be really meaningful if I could turn these images into a narrative film. Why? Because all the existing fiction films that we watch are made with acting.”

When Xu got his hands on his first batch of surveillance video through a friend, footage of a hospital car park immediately had his imagination running wild. “In the video, a woman takes a meal box into the hospital hurriedly. A man comes out of his car. They then speak to each other, and go their separate ways. When I started to make up stories about them, I knew that this idea should work.”