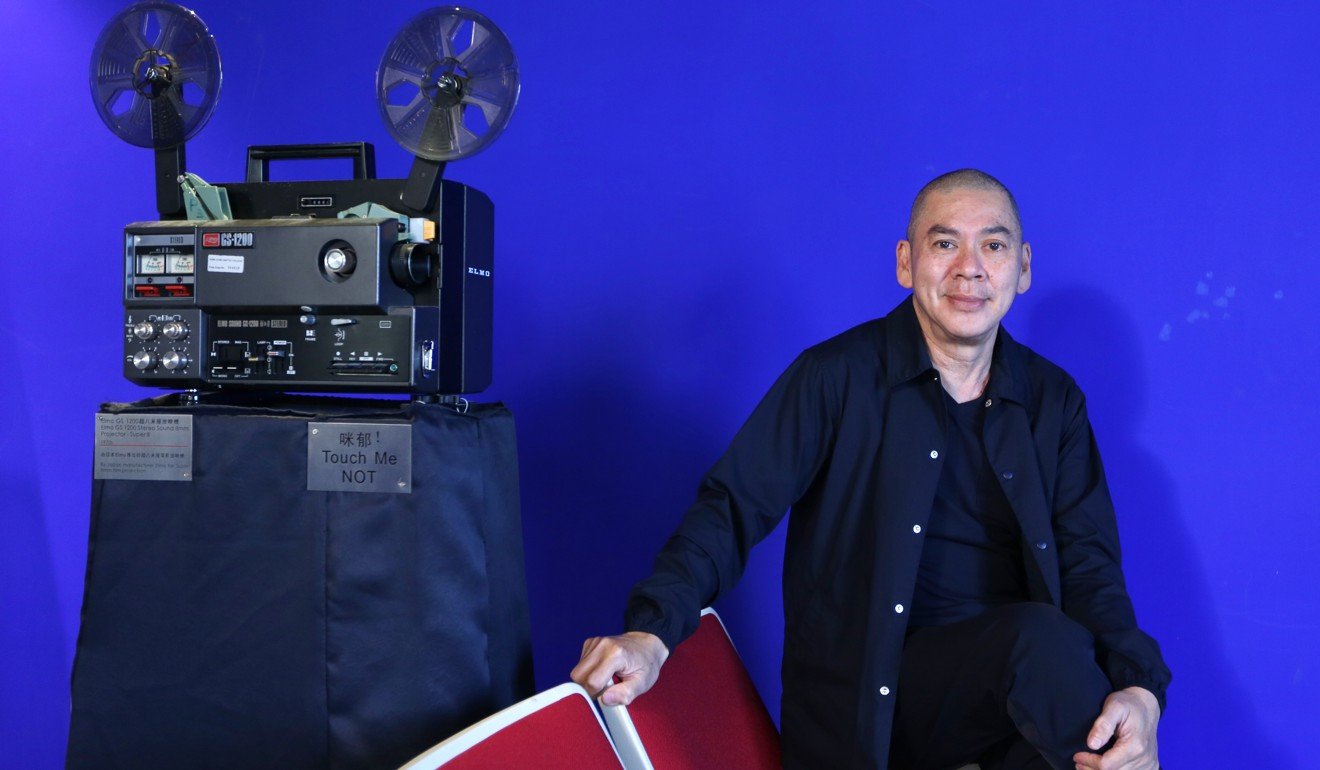

Taiwanese filmmaker Tsai Ming-liang on VR work The Deserted, showing in museums, and the film that fuelled his fish fantasy

He may be 60, but Tsai has branched out into the world of virtual reality, embracing 360-degree cinema in his latest work. The immersive story, with no dialogue, wowed crowds at the recent Hong Kong International Film Festival

While he remains one of the best-known art-house directors in Chinese-language cinema, the Malaysian-born, Taiwanese filmmaker Tsai Ming-liang has quietly moved away from traditional film distribution. Since his 2013 film Stray Dogs, Tsai has experimented with a variety of storytelling formats, from short films and documentaries to videos for performing arts projects.

His latest work The Deserted, which premiered at the Venice Film Festival in September and screened to a number of very lucky crowds at the recent Hong Kong International Film Festival, sees the 60-year-old filmmaker venture into the burgeoning field of virtual reality (VR) filmmaking.

Shot in an abandoned house in rural Taipei, The Deserted observes a sick man (Lee Kang-sheng, who is a fixture in Tsai films) as he passes his days in the company of his mother’s spirit (Lu Yi-ching, another regular), a fish he keeps in his bath, and one, or maybe, two female ghosts. Tsai’s signature use of static long takes appears to have found new life in the 360-degree cinema offered by the medium.

Tsai sat down with the Postduring his Hong Kong visit.

VR film technology is not suitable for close-up shots, and your films are sometimes notable for the absence of them. Does this make the two of you a great match?

I don’t know. Everything suits me. [Laughs] Maybe because I’m quite a self-centred person when I make films, I only think in my own way and not in any other people’s ways. I don’t think for the audience, either, because I’m the first audience of my film.

Filmmaker Tsai Ming-liang on sexuality and being touched by a goddess

Does VR suit me? Perhaps it does. But when people said [of The Deserted], “Oh, your scenes are getting shorter now,” I disagree. I think people may have that impression because they’re looking around. But I don’t think I’m doing shorter takes.

Does it bother you that your picture composition might be ruined because the audience can turn and look at the 360-degree space around them?

It’s true that the 360-degree visual offers a great deal of anticipation. But [my film] has only one focus, one direction. While VR tells you that you can look at all four directions, we [as filmmakers] just don’t tell you to do that. So you must allow them to look around, but you also hope that they don’t. I actually don’t want them to look around. My film doesn’t have that many things for them to look at.

Will you release a 2D version of this film so that more people can see it?

No. I don’t think it would look good. [For example], theatre wouldn’t look good if you watched it on tape. And if you adapt it into a film, then it’s no longer theatre. When I was in Beijing and Lee Kang-sheng asked me to buy him a [famous] roast duck leg, I found him a pre-packaged one. Back home, we cooked it according to the instructions, and it tasted awful. That’s just what films are like when you’re watching them on tape.

Film appreciation: Tsai Ming-liang's Rebels of the Neon God (1992)

When it comes to my films, you must see them on the big screen. It’s okay if you watch at home – my fans do that, too – but the casual audiences will have no idea what is going on. You lose a lot from that.

Most of the protagonists you create feature in a number of your films. Is this VR film a continuation of that?

It is. This film is mainly about Lee Kang-sheng’s character. From Rebels of the Neon God (1992) and The River (1997) to What Time Is It There? (2001) and Stray Dogs (2013), his character has gone through many different stages – just like a real person does. The fish he kept at home [in the earlier films], or his mother you saw in What Time Is It There? – they have both returned in this film.

Can you tell us more about the fish?

I haven’t mentioned this before, but the fish is related to my own film-watching experience. When I was three, the film I liked best was a 1959 Yue opera film called Zhui Yu [meaning Chasing Fish]. It was a Shanghai film that was very popular in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia. It tells the story of a female fish [spirit] who runs away. Its images have stayed with me. That’s why in my film, the protagonist is living with a fish.

Throughout your body of work, we’ve seen Lee’s character lose his parents, then his house in the city, and he’s now living in the middle of nowhere and talking to no one. What’s next for him?

I haven’t thought that far. But if someone approaches me to shoot something, then I’ll have something ready because I’m still living, and so is Lee. And even if I keep shooting him, it doesn’t mean that I have to keep developing this character. But Lee’s state of being [in the films] is something that I really want to hold on to. I think it’s interesting every time we revisit his character.

The Deserted is sometimes billed as the first VR film in Chinese-language cinema, but it’s ironic that there isn’t a single line of dialogue – Chinese or otherwise – spoken in it.

That’s just the way my films are. I hate dialogue. I’m not [like filmmaker] Wong Kar-wai. Lee has no one to talk to in this film, and that feels very natural to me.

Why do you think that you were invited by the Taiwanese tech company HTC to make this film?

I’d say that VR films may go into art museums soon, because it’s a form of artistic expression. [Video] games don’t go into museums, my work does, and that might be why they made this unusual decision [to invite me to make a film]. I’ve been making films for two or three decades, and my films don’t look like they’re making any money, but they do have their influences. They give people new ideas.

As you said, your films used to be screened primarily in cinemas, but in recent years they have been more frequently displayed in museums as video art projects. Do you see this as your new direction?

I need to clarify one point: whenever they invite me, I’ve always asked them not to describe my work as “video art”. It’s always been “film”. My work enters museums as film. I want the audience to see the films in the way that the director decides – and not that the cinema exhibitors decide.

Review: GayBird and Tsai Ming-liang make audience part of their show

My work is not video art. I’m a film director and I apply the artistic concept of films on my work. I may not always be able to show my films in cinemas, but I can show them in other places now.

Want more articles like this? Follow SCMP Film on Facebook