How No. 1 Chung Ying Street director Derek Chiu struggled with key moments in Hong Kong history – from 1967 riots to 2014 protests

Veteran filmmaker Derek Chiu saw promises of funding broken and constant production hassles, but at last his award-winning take on political protest in Hong Kong is to be screened in the city

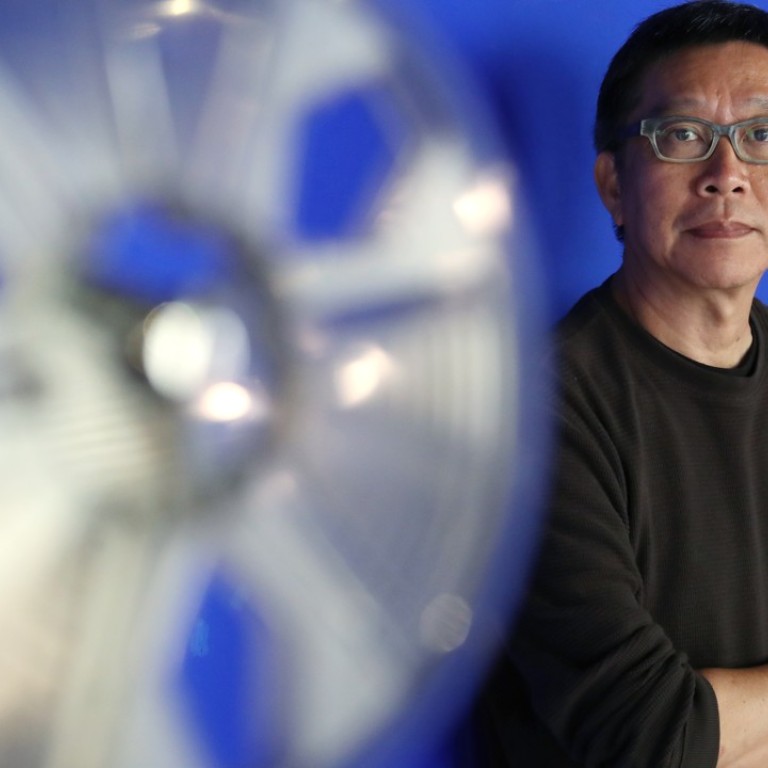

Veteran Hong Kong filmmaker Derek Chiu Sung-kee’s No. 1 Chung Ying Street won best picture at the 13th Osaka Asian Film Festival in March, but there was a time when he doubted whether the film would ever be screened.

Part of its focus is the deadly anti-British riots of 1967 in Hong Kong, an episode Chiu was prompted to research by someone who took part in them, and who approached him to make a film about the politically charged events, which were both a spillover from China’s Cultural Revolution and a radical response to colonial misrule.

The film’s story involves three young adults – Chun-man (played by Yau Hawk-sau), who attends a left-wing, pro-Beijing school, his childhood friend Lai-wah (Fish Liew Ziyu) and her rich classmate Chi-ho, (Lo Chun-yip) – who were caught up in the eight months of riots and bombings that left more than 50 people dead and more than 800 injured and only ended when then-Chinese premier Zhou Enlai called a halt.

Brother and sister tale depicts the torn Hong Kong society left behind by 2014 Occupy protests

To give the film added relevance for Chiu’s target audience – today’s young generation – he incorporated a second storyline about contemporary protest movements.

“We study history because it is a mirror to the future. The more I research, the more I realise how history is repeating itself,” says Chiu, noting the similarities between photos taken during the “umbrella movement” protests in 2014, also called Occupy Central, and those during the 1967 riots, especially those showing clashes between police and protesters.

I was constantly in fear each day, worrying if the production team would show up the next day

So the second part of No. 1 Chung Ying Street is set in 2019 and follows the lives of another three young adults – played by the same trio of actors. It shows them facing the consequences of their participation in the 79-day occupation of key roads in the city five years earlier to demand full democracy for Hong Kong, and at the same time defending a piece of farmland in Sha Tau Kok on the border with China, from property developers.

After the film was screened in Japan, audience members came up to Chiu in tears. “Because they do not have any presumptions and political stances, they [were] able to appreciate purely the work itself,” the director says.

Hong Kong cinemas won’t show Occupy documentary, Raise The Umbrellas filmmaker fears

In Hong Kong, though, the movie has polarised opinions. Some feel encouraged by it. “I see the universal longing for freedom and democracy,” said one audience member at a preview screening. Others see the film as biased and historically inaccurate.

“Hong Kong used to be an open-minded society that accepts different opinions. But now it’s not,” says Chiu, who says he felt the shrinking space for freedom of expression in the city while making the film.

With No. 1 Chung Ying Street featuring a controversial political incident, Chiu faced constant hurdles throughout its production.

He was urged by someone he knew who worked for the government’s Film Development Fund to apply for funding to make the film, but his application was ultimately turned down. The rejection came at a time when Ten Years, a film imagining a dystopian near future in Hong Kong, had stirred controversy. Chiu couldn’t help but wonder if the decision was political.

His suspicions were fuelled by what happened next.

He was denied permission to film in Sha Tau Kok, which is in a restricted frontier area.

Film review: Weeds on Fire – historic Hong Kong baseball team revived in coming-of-age drama

Even casting was a challenge. Actors turned down roles in the film without reading the script.

An actress who had agreed to play a supporting role as a housewife pulled out, telling Chiu she would rather not be involved in politics. Another actor, a Christian, claimed he could not take on a role because the Bible teaches him to obey those in authority.

“The society’s ignorance is creating this atmosphere of white terror,” says the director.

Casting for No. 1 Chung Ying Street did not involve any auditions. Instead, Chiu chatted with the actors to understand their views on social issues.

“I knew how well they can act from watching their previous films,” says Chiu. “Whether they truly understand the issue at hand, such as how a hot-blooded young man thinks, is more important.”

Take Fish Liew, for example. Though from Malaysia, she has seen similar democratic movements there.

Punched by police and shunned by cinemas, Occupy documentary maker still a believer

Without funding from the government, two other investors who had each pledged HK$3 million (US$383,000) also wanted to withdraw support. Chiu eventually convinced them to each invest half of the amount.

One investor suggested it might be God’s will not to make the film. “But I am a very stubborn person. I told him if this is God’s will, I will go against God,” says Chiu.

With only HK$3 million to work with – a third of the initial budget – Chiu relied on his friends, student volunteers, and industry professionals who offered their help for free.

“I was constantly in fear each day, worrying if the production team would show up the next day,” the director says.

Chiu has directed many movies and television shows during a 26-year career, including commercial films such as 2007’s Brothers, but this project is the one he cares about most, he says.

Joshua Wong on Hong Kong human rights, those CIA rumours, and his Sundance winner Teenager vs Superpower

The award in Japan, and screenings at the Far East Film Festival in Udine, Italy, in late April, have drawn attention to the film, and Chiu is optimistic it can secure a cinematic release despite its politically sensitive content.

The second half of the film addresses the sense of powerlessness that spread following the failure of the 2014 protests to deliver any concessions on democratic development in Hong Kong. Chiu is pessimistic about Hong Kong’s future, but believes that the key to resistance is action.

“And action is not limited to protesting on the streets. It can be articulating your views in an article,” says Chiu. “Or making a great movie.”

No. 1 Chung Ying Street will be screened on May 4 at Broadway Cinematheque, in Yau Ma Tei, and is tentatively scheduled for general release on May 31

Want more articles like this? Follow SCMP Film on Facebook