Their horror film was banned as a national security threat, so this Thai couple opened their own cinema

- Cinema Oasis was opened on family land in Sukhumvit in the heart of Bangkok

- The cinema shows films that don’t normally make it to festivals

What would you do if the government banned your films? In Thailand, a husband and wife team responded by building their own cinema.

Manit Sriwanichpoom and Ing Kanjanavanit (who goes by Ing K) had made a horror film in 2011 called Shakespeare Must Die, based on the Thai translation of Macbeth. A theatre troupe staged the Scottish Play in the film and they all came to a gruesome end because their vengeful government was sensitive to certain similarities between Shakespeare’s bloody tyrant and the ruler, Mekhdeth.

Horror master Stephen King sells movie rights to teenagers for US$1

Thailand’s real life censors under the Yingluck Shinawatra government banned the film as a national security threat because there were visual references to the paramilitary’s brutal crackdown of student protesters at Thammasat University on October 6, 1976.

As a provocative comeback, Ing and Manit made a film in 2013 using footage they recorded during their fruitless negotiations with the officials and called it Censor Must Die. The film censors gave it the green light, to their surprise. “Apparently, films recording events that really happened do not have to go through the censorship process,” Ing says.

But there was a catch. No cinema has dared show it because the government says it never gave the filmmakers permission to shoot in the Ministry of Culture office.

Having a cinema wasn’t a long-held dream, or even a thought-out plan to beat the censors. After all, having your own cinema doesn’t allow you to show banned films. But their anger, somehow, crystallised into a spontaneous idea that was triggered by a sudden windfall.

Ing’s eldest brother had sold a family plot around four years ago and split the proceeds between the four siblings. “He said to us, ‘What are you all going to do with this all this money?’ Nobody said anything. Then, these words just came out of my mouth: ‘I am going to build a cinema’. I didn’t know I was going to say that. The other three, instead of saying I was crazy, said that’s great!” Ing recalls.

It is important to have physical cinemas. People are always hunched over their phones. Their posture is horrible and the habit breeds an awful loneliness

The six-storey Cinema Oasis now sits on a plot of land that Ing’s great grandmother had bought in the heart of Bangkok’s thronging Sukhumvit area. (As an aside, Ing gleefully tells of how she once told Chow Yun-fat that the same great grandmother, and thus herself, were descendants of King Rama IV that Chow played in that infamous 1999 Hollywood version of Anna and the King.)

The cinema opened in March this year and has a 48-seat screening room with a five-metre screen and Dolby 5.1 surround sound system.

Designed by local architect Somchai Jonsaeng, the entire building is as full of character as the irrepressible duo: she, a feisty, razor-sharp former environmental journalist-turned filmmaker who exorcises her anger over politics and the abuse of women by painting violent, bloody scenes on canvas; he, a quiet and thoughtful activist/artist who started his Pink Man photographic series in 1997 as a critique of the economic and value system that plunged Thailand, and later the whole of Asia, into financial crisis.

A giant model of a pink flamingo stands by the entrance – a tribute to John Waters’ outrageous Pink Flamingos (1972). A wheelchair friendly ramp leads up to the foyer and a granny annex where friends can stay, surrounded by a lush, sunken garden.

The main section of the building is clad in an outer wall perforated with geometric shapes – a common feature in older low-rise Bangkok buildings that keeps the interior naturally cool. Inside, it is mainly raw concrete with numerous vintage wooden bookcases waiting to be filled with books about films.

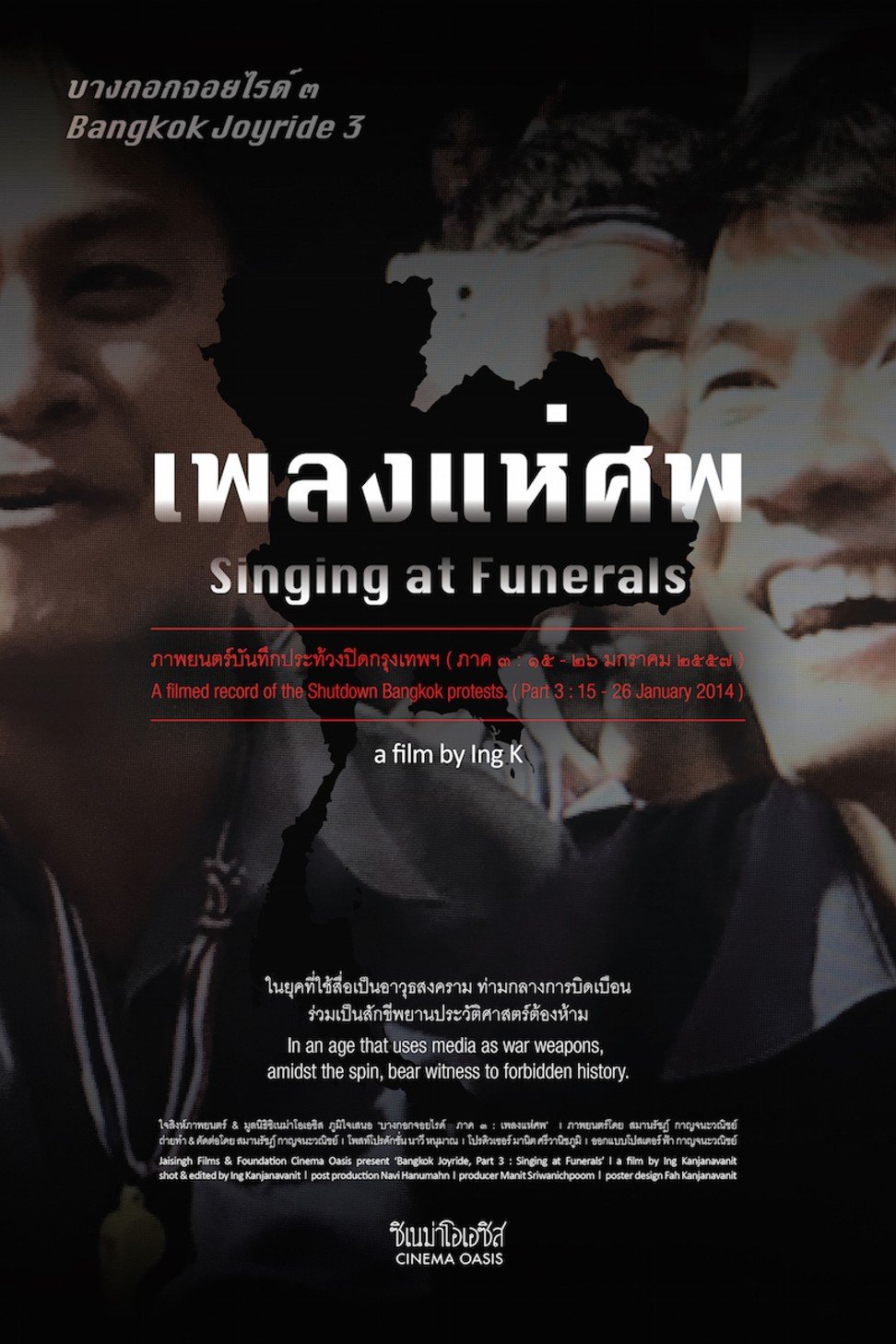

A gallery space on an upper floor is showing Ing’s agonised, violent and spiritual paintings and there are posters everywhere advertising southeast Asian gems that guest curators have picked out as having just missed selections for film festivals, independent works that are submitted on spec, as well as Ing and Manit’s unbanned works such as the three-part Bangkok Joyride that documented the 2013/2014 “Shut Down Bangkok” mass protests.

The ‘better angels’ of China-US relations are focus of Oscar winner’s new film

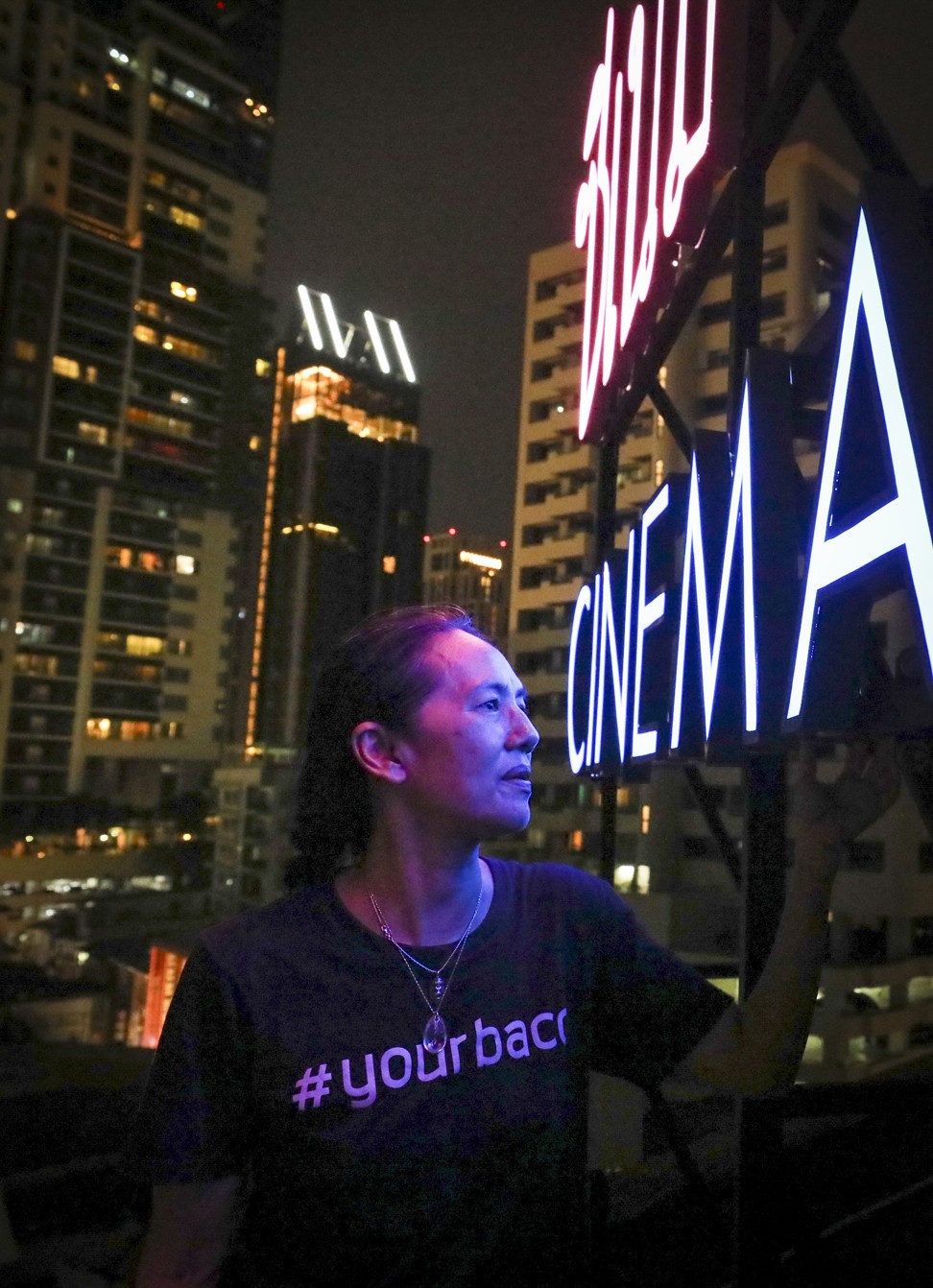

A giant neon sign bearing the name of the cinema glows defiantly on the roof, as the neighbourhood gets filled with more tower blocks and mega malls.

Manit says while the initial urge to build the cinema was fuelled by the outrage over the banning of their films, the main mission is to introduce people to films they don’t get to see normally and for independent filmmakers to get an alternative platform apart from commercial cineplexes and film festivals.”

“Our first programme was a series called ‘Beyond Pad Thai’, Thai films that are underrated and little known,” he says.

They won’t say how much they have spent on the building, which they rent out for private functions and screenings to subsidise the operating costs. It’s worth every cent, they say, even if bricks-and-mortar cinemas are anachronistic in this era of on-demand streaming.

Ing says they decided to hire an architect to build a “really nice building” because she hopes her nephews and nieces will be tempted to hang on to it rather than sell the land for yet another luxury commercial development. “The land is really valuable now that this has become shopping centre country. The building is also a way of honouring the films,” she says.

Before the love: when Twilight fans hated Robert Pattinson as vampire Cullen

“It is important to have physical cinemas. People are always hunched over their phones. Their posture is horrible and the habit breeds an awful loneliness. I just want to get people to put that thing down, lean back, look up to the big screen and have a communal dreaming session with other people. This is war against human devolution,” she says.

“We want to compete with technology. Technology makes us forget our physical reality. If everyone surrenders to their phones then we are finished,” Manit says.

At the end of the day, they concede that cinemas are going out of fashion. “Even multiplexes are struggling to get audiences. But we are still opening a cinema at this time. It is an act of defiance,” says Ing.

To learn more about Cinema Oasis, visit cinemaoasis.com.

Want more articles like this? Follow SCMP Film on Facebook