Jailed for life in California, denied parole 12 times: how Chinese-American found redemption after prison

- A Chinese immigrant arrested at 16 and tried as an adult for kidnapping and robbery, Eddy Zheng spent 21 years behind bars

- A model prisoner who, since his release, has helped inmates and at-risk youth, he is the subject of an award-winning documentary about his life

Eddy Zheng Xiaofei, 49, is personable, talkative, and optimistic as he eagerly lists his achievements of the past few years. It’s hard to imagine that he spent 19 years in a California prison, where he was denied parole 12 times.

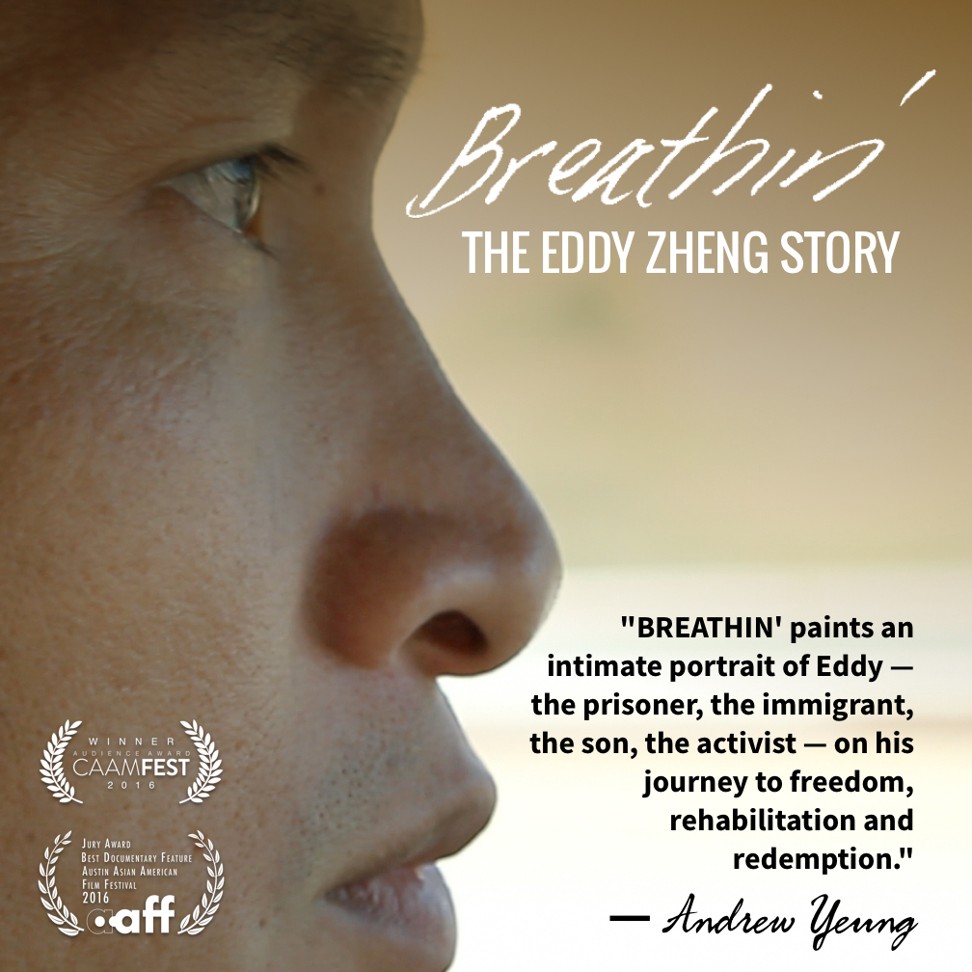

The Chinese-American does not shy away from talking about his time in jail; he recounts his story in a 2016 documentary called Breathin’: The Eddy Zheng Story, which will be screened at Asia Society Hong Kong tomorrow night.

California police investigate ‘possible hate crime’ against Chinese-American

The 60-minute film documents a crime committed by Zheng 30 years ago, and how he managed to turn his life around during his time in jail. It also highlights how the US justice system can deny a model prisoner his freedom.

Zheng was born and raised in the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou. His father was a People’s Liberation Army officer and his mother a government accountant. They met playing basketball, and he recalls proudly watching his mother on the court when he was a child.

“My older brother, sister and I went to school; our aunt took care of us. We had a structured life where we ate meals together. I didn’t need to do chores. I had whatever I wanted,” he recalls.

His maternal grandparents had immigrated to the United States and Zheng didn’t meet them until he was 10 years old, in 1980, when they returned to China for a visit. His parents decided to follow on, sacrificing their careers in the hope that their three children would have a brighter future.

However, when he arrived in Oakland, California, in 1982, the adolescent Zheng was lost – in a new country, facing culture shock and knowing no English.

Seven family members were crammed into his grandparents’ two-bedroom flat, the children sleeping on sofas for seven months before they found another flat. Zheng’s father and older brother started working at Burger King, while his mother became a live-in nanny for another family, returning home only one night at weekends. As a result, Zheng had little money and was largely unsupervised.

At school he was mocked, taunted and bullied, and could not comprehend what his teachers were saying. Although he had been an average student in Guangzhou, here he was lumped into a class with other immigrants – Mexicans, Southeast Asians and other Chinese – with varying language abilities.

Unhappy, he began bunking off school, and intercepting students who were tasked with delivering letters to his parents detailing his absences. Before long, he found himself hanging out with other wayward Chinese youths who dabbled in petty crime.

“We would go shoplifting and take a jacket, or burgle cars to get stereos to sell them for money,” he recalls. In the documentary, he mentions he worked as an armed guard for a prostitution ring, protecting a brothel.

On the night of January 6, 1986 – a date forever emblazoned into Zheng’s memory – his life took a dramatic twist. The 16-year-old and two friends armed with guns broke into the home of a relatively wealthy Chinese family. They shut the two children in the bathroom, and tied up the father and mother with a telephone cord.

Zheng stripped the mother naked and pretended to take photos of her with a camera that had no film in it, to intimidate her into reveal where their valuables were kept.

Ransacking the home, they found little other than keys to the victims’ business. So Zheng and a friend forced the woman to drive them to the address, where they got away with US$34,000 in cash, jewellery and merchandise.

When I first arrived in prison I didn’t have any skills and didn’t know much English, so my first job was washing soiled laundry that paid 19 cents an hour

Fatefully, while driving the woman home, Zheng forgot to turn on the car’s headlights and they were stopped by police officers, who arrested them for robbery and kidnapping.

“I didn’t understand the seriousness of the crimes. I thought I would get out,” says Zheng, who had been arrested previously for shoplifting and attempted burglary.

Being unfamiliar with the justice system, and unable to afford a lawyer, Zheng’s family believed the best option for him would be to plead guilty and face punishment.

They didn’t foresee that he would be charged as an adult for robbery, burglary, possession of a firearm, unlawfully entering a residence, and one count of kidnapping – earning him a life sentence in prison.

Zheng was the youngest prisoner at California’s San Quentin State Prison, and was terrified, but tried not to show it. “I had to learn how to survive and try not to get bullied or raped,” he says. So Zheng hunkered down to focus on learning English, one word at a time with a Chinese-English dictionary. This enabled him to eventually pass the General Education Development (GED) test – the equivalent of graduating from high school – at his first attempt.

“When I first arrived in prison I didn’t have any skills and didn’t know much English, so my first job was washing soiled laundry that paid 19 cents an hour,” he recalls.

“But when I passed the GED, I immediately felt confident and wanted to read more. I learned how to type … and then I became a clerk who takes down the inventory of prisoners who come in and leave. That paid 30 cents an hour.”

How Chinese investors are pumping billions into the US West Coast

He later learned how to repair air conditioners and refrigerators, and continued academic classes in the evenings. To make contacts on the outside, Zheng also began sending letters to local community leaders and activists.

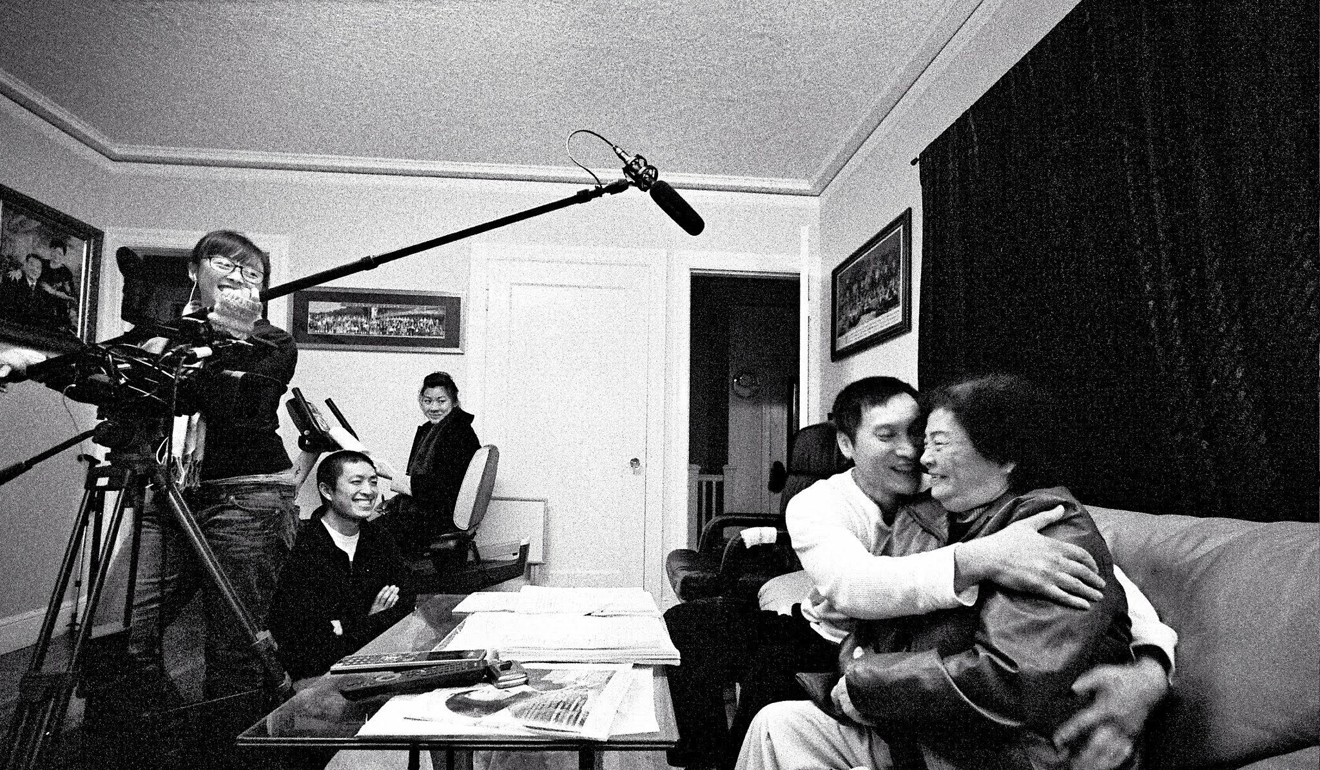

One of them was Ben Wang, who directed and produced Breathin’. At the time Wang, now 36, was a student sitting Asian-American studies at University of California, Davis. He began corresponding with Zheng and visited him frequently in prison, and encouraged other students to visit prisoners.

Wang later became one of many vocal advocates for Zheng, who’d had a difficult start as an immigrant in the US, strayed into crime, then turned his life around and become a model prisoner, only to be denied parole 12 times.

The subsequent publicity about Zheng’s situation led to growing calls from the Chinese-American community for him to be released. Prison authorities, however, continued to insist that he was a “danger to society”.

On March 8, 2005, after 19 years in prison, he was released, only to end up in an immigration jail for a further two years. While he had been serving his original sentence, a change in the law meant immigrants who had been convicted of a crime faced deportation.

However, because many community leaders had written to the authorities that Zheng would be a benefit to society, he was finally freed on February 27, 2007.

After his release, Wang persistently urged Zheng to collaborate on a documentary and, after he agreed, filming began in 2010. It was a four-year process, during which Wang revisits Zheng’s crime, his protracted parole hearings, and how he has become a community leader working with at-risk youth and inspiring prison inmates.

One of Wang’s toughest tasks in making Breathin’ was finding archival footage of Zheng.

“Eddy told me about this woman who had shot film of the parole hearings and had family footage in a storage shed in her father’s home … I got in contact with her and eventually we went to the shed and it was like a scavenger hunt. We went through all the boxes until we found the tapes. We were so lucky they weren’t damaged by the weather and from being in the shed for years,” Wang recalls.

In a pivotal moment in the film, Zheng writes a letter in Chinese to the woman he victimised more than two decades earlier. He apologises for the trauma he caused her and her family, and says he is trying to right his wrongs by helping the community.

The independently made film had its premiere in San Quentin State Prison in 2016. Wang says this was a deliberate choice, as the prison allowed them in to film and they wanted Zheng’s friends there to see the documentary.

Soon afterwards, it was shown at the Center for Asian American Media Film Festival, where it won the Audience Choice award. Breathin’ has since been screened at a few US film festivals, and aired on public television last year.

“It’s really rewarding. People are really responsive to the film,” Wang says.

Zheng recently set up a foundation called New Breath, which helps Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders who have been impacted by incarceration and deportation.

In 2012 Zheng got married, and he and his wife have a five-year-old daughter. Will she eventually get to learn the Eddy Zheng story?

“She will. I don’t know how she will react,” he says. “But she’s smart and curious, a very kind person. Hopefully she will be proud of me.”

Eddy Zheng and director/producer Ben Wang will attend the screening of Breathin’: The Eddy Zheng Story on December 4 at 6.15pm at Asia Society Hong Kong, 9 Justice Drive, Admiralty. For more information visit asiasociety.org.hk.