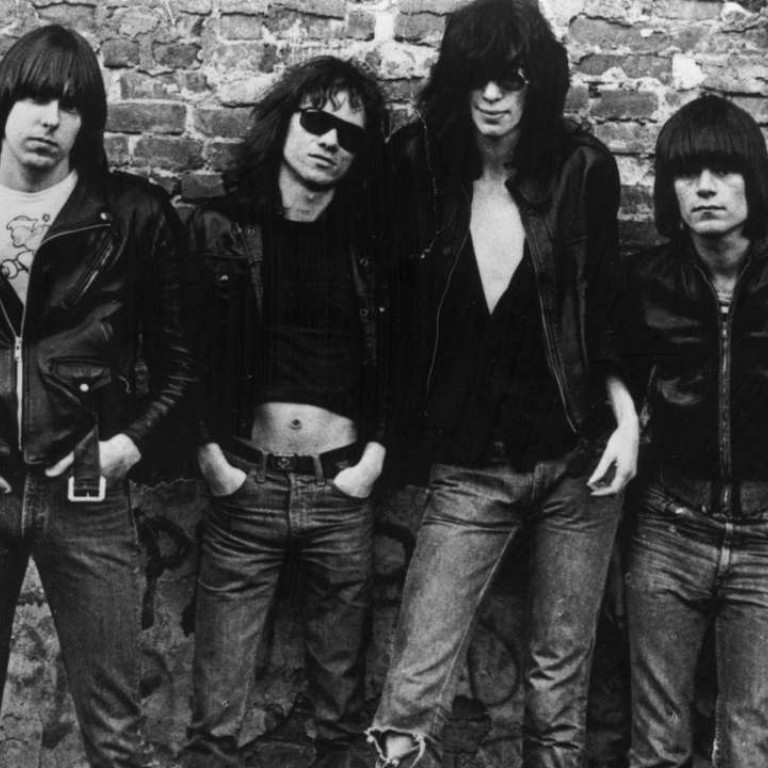

Play looks inside punk legend The Ramones’ notorious partnership with Phil Spector

Written by actor and playwright John Ross Bowie, Four Chords and a Gun focuses on the tumultuous production of the band’s fifth album, End Of The Century

“I think punk rock needs an Amadeus,” says actor-turned playwright John Ross Bowie, referring to Peter Shaffer’s 1979 drama chronicling the tension between Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Antonio Salieri.

Punk rock gets a tragic reading in Bowie’s play, which zeroes in on the balance between the group’s staunch anti-establishment tendencies and its desperate desire for more fame. Tracking the behind-the-scenes construction of 1980s End of the Century, an album the Ramones recorded with the eccentric Phil Spector, Bowie aims to articulate how the varying expectations of the members of a rock ’n’ roll group clash to form something rather combustible.

Did End of the Century give the Ramones the breakout hit they desired? Students of rock ’n’ roll history know the answer is no, but Bowie’s work attempts to show the effects of ego and compromise on the band dynamic.

“There’s a lot of push-pull,” Bowie says of the Ramones captured in the production, directed by Jessica Hanna, Bootleg’s producing and managing director. “Yes, the band all wants to be rock stars, but they all have very different visions in how that will be accomplished and what that will look like once they’re there.”

This is what fascinated Bowie, who is perhaps best known for his recurring role as Barry Kripke on hit US TV show The Big Bang Theory.

“I saw that as interesting and not a very binary conflict,” he says. “It’s not just, ‘This person wants this thing, and there’s something standing in his way.’ They’re in each other’s way. They’re in their own way.”

For Ramones fans, the recording sessions for End of the Century are the thing of myth. The band were accustomed to a no-fuss, no-frills approach in the studio, while Spector would obsess over a singular guitar part for days. Depending on which tale you believe, Spector even pulled a gun on the band.

Bowie toys with this unknown history, using the violent sessions to show the discord in the already dysfunctional relationship between what’s shown as an earnest Joey Ramone, portrayed by Matthew Patrick Davis, and a more bullish Johnny Ramone, captured by Johnathan McClain.

In real life, the two supposedly didn’t speak much for the bulk of the career of the band, and Bowie attempts to get to the heart of the rift.

“I always loved the fact that there were so many conflicting stories about how all the stuff went down with Phil Spector,” Bowie says. “There’s versions where he’s drawing a gun on them constantly. There’s a version where he just puts the gun on the mixing board to threaten them. There’s a version where he keeps them hostage in his house until late the following day. I love that this incredibly recent history is as disputed as the Crusades.”

Still, Bowie tried to ground as much of the story as possible in fact, reading every Ramones book he could find. A key source, he says, was I Slept With Joey Ramone: A Punk Rock Family Memoir, written by Joey’s brother Mickey Leigh, with Legs McNeil.

The play, which runs until July 31, opens to the tune of the Ramones’ We’re a Happy Family, the irony of the song soon playing out onstage. Johnny in the play serves as a sort of de facto leader, keeping tabs on money and bookings, while Joey grapples with his OCD tendencies and his own dreams of wanting to be a rock star.

There are women troubles, but producer Brian Nitzkin says he was drawn to the production because it avoids many of the cliches seen in rock ’n’ roll narratives.

“What I was really taken with is that it wasn’t your stereotypical rock ’n’ roll story with trashed hotel rooms and 24-hour debauchery,” he says. “It was about these guys who looked at it like a job.”

With a mix of independent financing and more than US$20,000 raised via crowd-funding site Indieagogo, Four Chords and a Gun began rehearsals on May 31.

Since today’s audiences are familiar with Spector’s ultimate fate, knowing that the artist was convicted of the 2003 murder of actress Lana Clarkson, Bowie says he was nervous that the character would become a caricature. Onstage, he’s certainly outlandish. Audience will first see Spector (portrayed by Josh Brener) brandishing a cape.

But Spector is just one of many elements of contention among bandmates.

“I was very careful to make sure that there isn’t one steadfast villain in the piece, and to make sure that there isn’t one steadfast golden boy,” Bowie says. “I think it’s very easy to see what the play is about and be like, ‘Either Johnny, who was a notorious [jerk], or Phil, who is a convicted murderer, those are going to be the bad guys.’ I worked really hard to make sure it was never that simple and that there was enough ambiguity in the characters as there is in real people.”

One thing that does not happen in the production: The fictional Ramones never play a song. Bowie focuses tightly on the off-stage theatrics. “This isn’t Jersey Boys,” he jokes.

As to whether such a rebellious form of music belongs on the more refined stage of the theatre, Bowie has a quick and ready answer.

“The bottom line is we go to theatre to vicariously spend time with really intense characters,” he says. “The six characters in this play are pretty intense. I tried to, for the moment, bottle that.

“There’s something tragic about the show. These guys’ tragic flaw, if you want to put it in grand and mythical terms, was the need to be famous or be loved. They went to great, crazy lengths to do that, and it didn’t quite work in their lifetimes. Tragedy is the oldest form of theatre.”