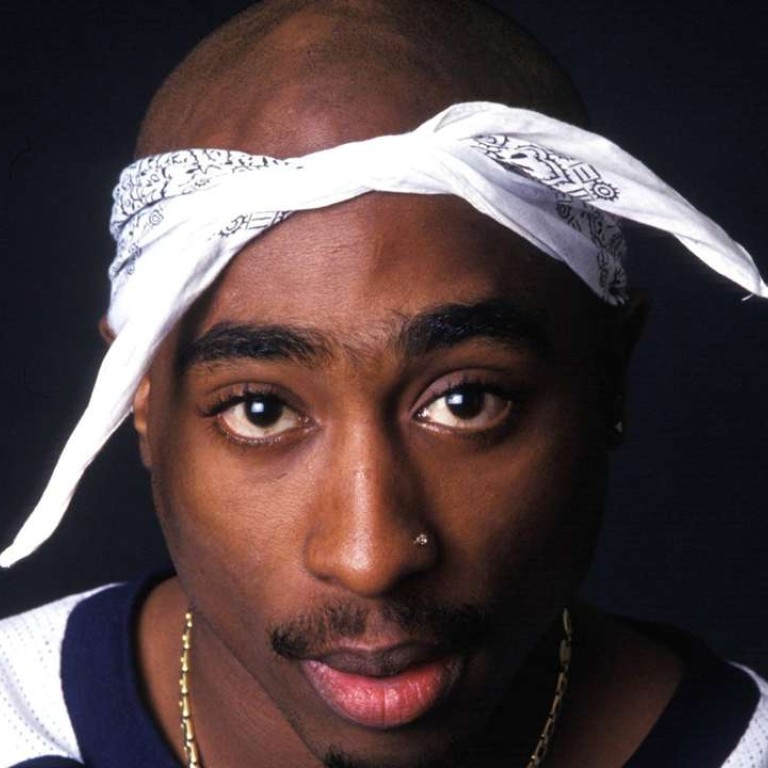

Why Tupac still reigns in hip hop 20 years after his death, and why his legacy is at risk

From hologram performances at Coachella to seven posthumous albums, rapper Tupac Shakur has stayed relevant. But the death of his mother – who controlled the Tupac brand – may change everything

Two of the most awaited (and most acclaimed) recent hip hop albums came from Kendrick Lamar and Frank Ocean. On the final tracks, each album hit a familiar note – the rappers invoked Tupac Shakur.

When rapper Khaled M. visited his ancestral Libya after the fall of dictator Muammar Gaddafi, he was startled to see likenesses of Tupac and another late music legend, Bob Marley – plastered on the walls in a country far removed from English-language pop culture.

Twenty years after his death, Tupac still reigns. Other rappers have eclipsed his stardom, and the promotion of Tupac has been haphazard, but the artist, who died at age 25 on September 13, 1996, maintains a hold that is among the most enduring in recent times.

“He represented, more than anything, just that angst for people who felt oppression and poverty or who felt marginalised,” says Khaled M., the US-raised son of Libyan dissidents who has gone on to a rap career. “He was the voice of the voiceless. Up until this day, I don’t think we have a hip hop artist being able to replicate all of his voice, or his depth and passion.”

His emotional directness and range – from prophetic warnings of his violent death to making maternal affection acceptable for a gangsta rapper – helped Tupac’s music transcend borders.

Global artists who have cited his influence include DAM, the pioneering political Palestinian hip-hop group, and rappers in Iran, sub-Saharan Africa and eastern Europe. His influence was not always a positive one; during the brutal civil war in Sierra Leone, West Africa, guerillas donned Tupac T-shirts as fatigues and took his aggressive Hit ’Em Up as an anthem.

Tupac was shot on September 7, 1996, in Las Vegas, and died of his injuries six days later. His murder officially remains unsolved and his fate has fascinated conspiracy-minded fans, with a photo going viral just last month of a man in South Africa who internet users insisted was the long-lost rap messiah.

The Los Angeles Times, in a lengthy but controversial investigation in 2002, tied Tupac’s killing to the Crips gang. His death came at the height of a vaunted rivalry in the US, egged on by promoters, between east coast and west coast hip hop, with leading New York rapper The Notorious B.I.G. slain six months later in Los Angeles.

Tupac was born in New York and raised in Baltimore, but became one of the most identifiable figures in the west coast scene centred around Suge Knight’s Death Row Records.

He had repeated brushes with violence and went to prison in 1995 on sexual assault charges, with his Me Against the World becoming the first No 1 US album by a serving inmate.

Yet Tupac’s identification as a gangsta rapper came late in life. The future icon entered the hip hop world not as a tough guy but as a cheery backup dancer for the sensual Digital Underground and, despite the assault allegations, was one of those rare rappers to condemn violence against women.

As his career boomed in the 1990s he became a successful actor, starring across Janet Jackson in Poetic Justice and playing a conflicted gang member in Juice. He also gave long, introspective interviews, one of which was sampled at the end of Lamar’s acclaimed 2015 album To Pimp a Butterfly.

Tupac – whose mother, Afeni, was active in the Black Panther movement and named him after Tupac Amaru, the 18th-century indigenous revolutionary in Peru – also raised issues facing African-Americans, from police brutality to mass incarceration.

The message was not in itself groundbreaking – since the 1980s, artists such as Public Enemy, N.W.A. and KRS-One have brought politics into hip hop. But Michael Jeffries, an associate professor of American Studies at Wellesley College, in the US state of Massachusetts, says Tupac possessed a dramatic flair and emotional energy like few other rappers in history. “You don’t have to speak the language fluently to understand the narrative,” he says.

Tupac also emerged at a propitious moment, Jeffries said. Hip hop had just gone mainstream and, with the music industry’s downturn still several years away, record labels were investing heavily in artists.

“He is uniquely positioned to capitalise on it, not only because he’s a talented rapper but because he’s a gifted actor as well. He becomes a true crossover celebrity precisely at the time that money is flowing into the business,” he says.

Tupac was “resurrected” in 2012 at Coachella, one of the world’s pre-eminent music festivals, where he performed as one of the first concert holograms alongside former associates Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre. Yet despite his global persona, few formal tributes exist for Tupac, whose mother said she spread his ashes on her North Carolina farm.

His mother had sought to direct his legacy through a youth art school near Atlanta in the southern United States, funded through the seven Tupac albums released posthumously. But the school – with its bronze statue of Tupac – has closed and Afeni died in May this year.

Travis Gosa, an assistant professor of Africana Studies at Cornell University in New York, voiced concern for the future of the defiant rapper’s legacy in an era when tickets for the hip hop musical Hamilton fetch hundreds of dollars.

“One thing that is ironic about Tupac 20 years after his death is that you can go to a Starbucks coffee shop and hear Tupac playing on the speakers,” he says.

He said that Marley’s example showed the need for caution. Since his death in 1981, Marley, whose music was driven by messages of uplift and pan-African resistance, has been relentlessly commodified in T-shirts, posters and even marijuana brands with little connection to his causes.

His mother “did the best while she was alive to really use the branding cachet of Tupac’s name to do something that goes beyond just generating money. Now that she’s gone, I’m not sure what’s going to happen,” Gosa says.

“People are able to rent out their own Tupac hologram now. I think we need to be vigilant about what the Tupac brand is going to be 10, 20 years from now.”

Agence France-Presse

.png?itok=arIb17P0)