China’s hip-hop culture ban: authorities send mixed messages

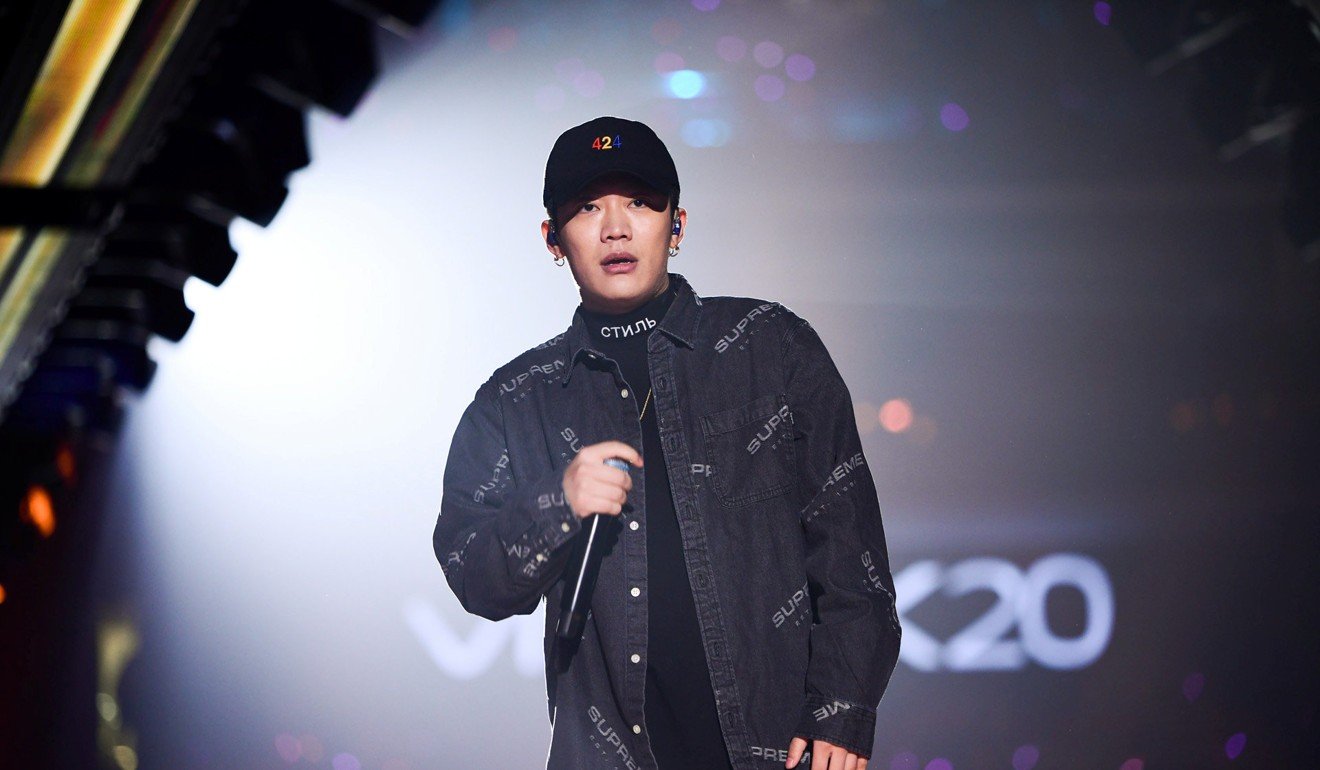

A recent televised rap competition drew three billion viewers in its three-month run, but some rappers, and hip hop as a whole, have faced official scrutiny. New shows are still being released, though, with apparent approval

Although rules specifically targeting hip hop were not available on official platforms, Chinese news site Sina Entertainment reported in January that regulators had requested that television programmes avoided guests associated with the genre.

Hip hop in China bounces back as new show gives next-gen rappers mainstream appeal, despite censorship

Still, Hot Blood Dance Crew, a dance competition which shows the influence of hip-hop culture, premiered on online video platform iQIYI in March. That came just weeks after Street Dance of China – a similarly themed programme – began screening on Youku, another Chinese video site.

At first glance, both programmes appear to have much in common with last year’s breakout rap competition The Rap of China, which drew nearly three billion views during its June to September run, but has since seen its stars come under scrutiny.

Chinese American rapper and hip hop star on his rise and why he turned down The Rap of China – twice

The newer programmes, however, were released months after authorities began suppressing some aspects of hip-hop culture.

PG One, one of the winners of The Rap of China, made a public apology in January after accusations that lyrics in one of his older tracks encouraged drug use and misogyny. The rapper’s other tracks were subsequently pulled from various music-streaming platforms in China, online news site Quartz reported.

Despite all that, there hasn’t been any official pronouncement from Beijing explaining the apparent suppression. Emailed requests for clarification on the government’s position to China’s media regulator and its Ministry of Foreign Affairs were not immediately returned.

Seven Chinese hip-hop acts who’ve leapt the Great Firewall to make China look cool

“Generally, restrictions tend to be unclear. It’s quite a deliberate approach,” says Merriden Varrall, director of the East Asia Programme at Australian think tank the Lowy Institute. That allowed regulators to selectively come down on some hip hop-related programmes, but not others.

The use of “strategic ambiguity” by authorities meant that hip-hop practitioners would likely self-censor, says Varrall. If regulators had been absolutely clear on where they were drawing the line, that would have given people the confidence to go up to the edge of what’s allowed, she added.

Against that backdrop, participants in the industry told Billboard earlier this year that the so-called hip hop ban was not an absolute crackdown, but a targeted move aimed at filtering out specific elements.

For China, that raises questions about the development of hip hop, a genre that’s steeped in rebellion.