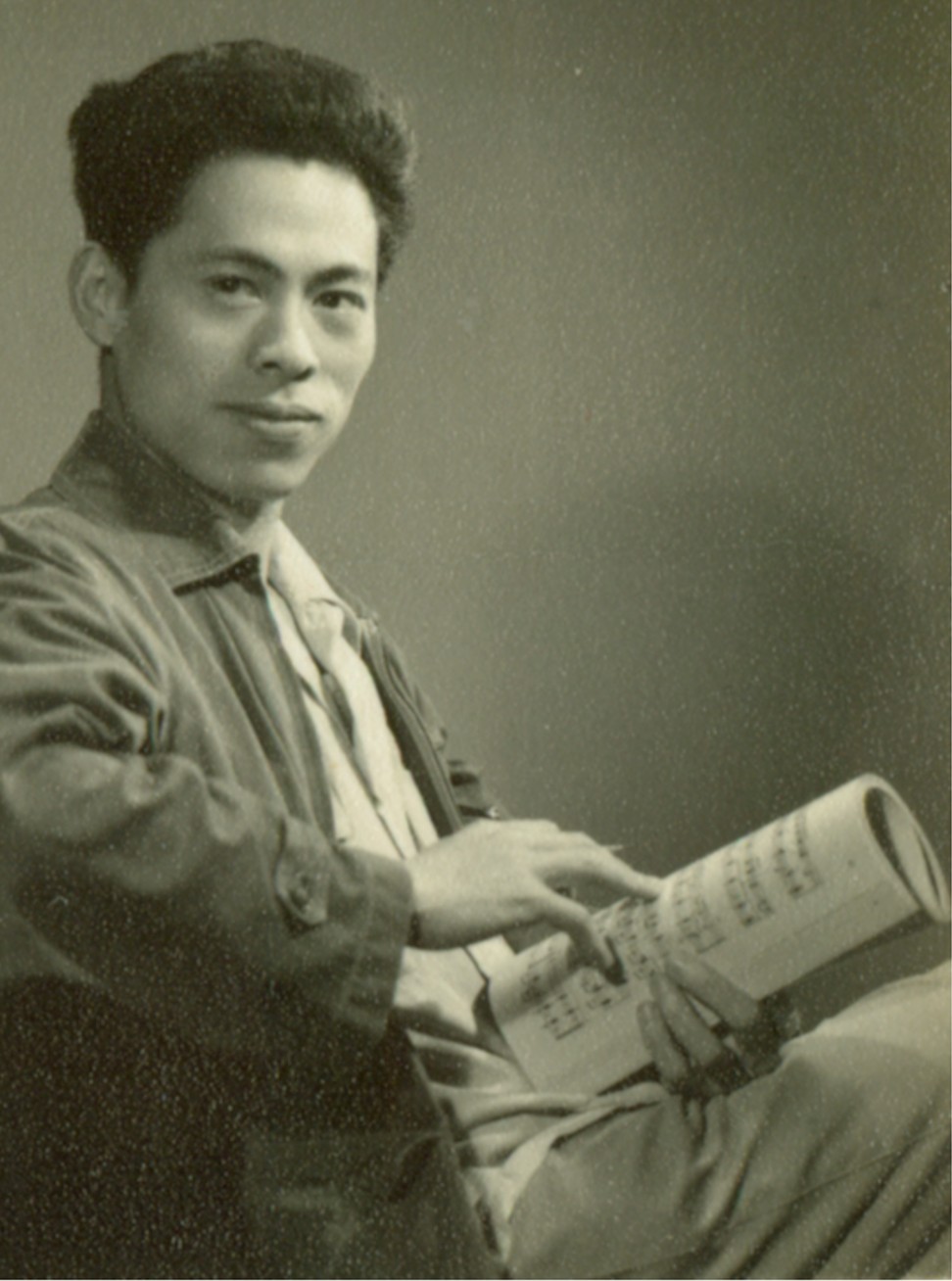

Chinese composer recalls birth of The Butterfly Lovers violin concerto 60 years ago

He Zhanhao was a first-year student when he co-wrote his most famous work with classmate Chen Gang. Now 85, he will conduct a performance of it in Hong Kong today

He Zhanhao was a first-year student at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music when was ordered to write a concerto. The then 24-year-old did so with great reluctance, feeling unqualified for the task.

Little did He know then that the piece, The Butterfly Lovers violin concerto, which he co-wrote with classmate Chen Gang, would become one of the most well-known Chinese classical music works.

HK Phil on top of their game in pulsating Rachmaninov

That was 1958. The piece premiered a year later in a concert celebrating the 10th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China, with 18-year-old Yu Lina on the violin.

“It is a pioneering piece, the first classical violin concerto to be written by Chinese,” says Huang Mengla, a student of Yu who has performed the concerto with various orchestras, including the Staatskapelle Dresden in 2012. “Though from the perspective of Western composition the piece is not perfect, its unique historical background and the influence it had on the generations that followed enabled it to leave its mark in musical history.”

This year marks the 60th anniversary of its composition, and to celebrate it the Nanjing Philharmonic Orchestra will perform the piece in an outdoor concert in Hong Kong on Thursday evening. He will conduct the performance on the Victoria Harbour waterfront in Tsim Sha Tsui.

The story of the violin concerto begins a little before He was given his fateful assignment at the Shanghai conservatory.

“We were taught that art performers serve the people and not ourselves,” recalls He, now 85, echoing a Mao Zedong slogan. At the time, there was a disconnect between classical musicians and their audiences. “What they wanted to hear, we didn’t know how to play. And what we played, they didn’t understand.”

He recalls one particular concert, where they were performing music by Beethoven and Bach. The crowd left one by one to a point where there were more performers on the stage than audience members sitting in front.

“One old woman stayed till the end, so we were very touched and asked her why she enjoyed our music,” He says. “I am waiting to collect the chairs you were sitting on,” came the unexpected answer.

Realising the need to create music for the local audience, he and some classmates formed an experimental group and tried adapting Chinese traditional folk music. As the son of a Shaoxing opera singer and having played in the Yueju Opera Troupe in his hometown of Zhejiang, He was well versed in folk music.

Drawing from the legendary love story of Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai, and the Chinese opera relating to it, He wrote his first string quartet, or what he likes to call “the little Butterfly Lovers”.

It was only a draft and he did not intend for it to be played.

What they wanted to hear, we didn’t know how to play. And what we played, they didn’t understand

But when a visiting Czechoslovak string quartet asked if there was a Chinese musical piece that they could play, a classmate said He had written one. Pressed by his superiors, he hesitantly produced two crumpled pieces of paper – the original scores of the little Butterfly Lovers. Unfortunately the string quartet could not interpret what was written down.

The next day, he was summoned by the director of the conservatory, demanding to know what he had written and why the visiting ensemble could not interpret the score. It was because He incorporated a lot of glissandos in his piece, a common technique in Chinese music where the musician glides from one note to another. And he invented his own ways to notate the glissandos – a wiggle here, an arrow there and some dots.

He was told to rewrite the piece, which he did with the help of a cellist, who was enthralled by the task. “For 10 years, I have learnt to play the cello. And all the bowing and fingering are notated by people with blue eyes and long noses. For once, it is vice versa and done by people with yellow skin and black eyes,” he joked to He and added: “Let’s make it more difficult so they can’t play it.”

“The cellist pointed out the complicated emotions of our generation – the first generation of youth since the new China was established,” He says. “On one hand, we were ashamed because we were such a large country yet we did not have a single piece of music for a string quartet. On the other hand, we were dignified, and thought, if they can do it, why can’t we?”

He was also impressed by the visiting ensemble’s professionalism. “They really respected works with Chinese characteristics. It did not matter that it was written by an inexperienced freshman.”

With the success of his string quartet came orders to aim for a bigger prize – writing a violin concerto.

His group came up with various themes. It was during the Great Leap Forward, so one suggested writing about peasants engaging in backyard steelmaking. Another proposed a piece based on Chairman Mao’s proclamation that “women hold up half the sky”. Their superior ultimately picked the third proposal – converting the Butterfly Lovers string quartet into a concerto. In hindsight, his was the only choice that would have stood the test of time.

Violinist Huang says: “It may be an ordinary love story. But through it, many people see their own past and memories. They can relate to the injustice, powerlessness, resistance, struggle and pursuit for a better life portrayed in the story.”

Opportunity knocks for musicians in China; youth orchestra helps

At the time, however, He was still unsure. As a violin student – and not an outstanding player, he admits – he had little experience in composition. He also stubbornly resisted orders from his superiors. Finally, though, he was persuaded to take on the challenge by flute teacher Liu Pin.

“Do you think the maestros such as Beethoven and Bach were born with music in their brains? No. They also used folk music for inspiration and materials,” Liu told He. The flautist also left him a note with, of course, a few more of Chairman Mao’s quotes, such as: “Emancipate the mind, seek truth from facts... .”

Now convinced, He toiled away with Chen Gang under the tutelage of their teachers for several months.

“A lot of people now overpraise us for composing the piece but that is not accurate. Without our teachers’ instruction, we would not have been able to accomplish the task,” he says. The Butterfly Lovers violin concerto received its premiere a year later, in 1959.

He was also on the stage as a violinist. “I usually sat at the back but they placed me as second violin to honour my role as the composer,” He says. “After our performance ended, there were a few seconds of silence and I thought to myself, ‘It’s over. They didn’t like it’.”

But then came thunderous applause and even calls for them to replay the piece. He pauses to revel in the memory of that moment.

Liu later told He: “Your work will probably leave a mark in history.”

He later transferred to the composition department and studied under Chinese composer Ding Shande. Though the piece was temporarily banned during the Cultural Revolution (it was branded “bourgeois”, according to the Naxos Music Library), it was revived afterwards and has since remained popular.

A lot of people now overpraise us for composing the piece but that is not accurate. Without our teachers’ instruction, we would not have been able to accomplish the task

He went on to compose many more pieces in the decades that followed, covering a wide range of genres, from classical works such as A Diary of a Martyr for string quartet to pop music, including a song for Canto-pop singer Paula Tsui Siu-fung.

Today, with his hair dyed black and in high spirits, He looks younger than his age. Despite being well past retirement age, he remains active and incredibly busy.

He has just returned from Hangzhou, where he held talks, and was flying the day after this interview to Beijing for a concert at Peking University. We met up at his modest flat, conveniently located between the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra Hall and the Shanghai Conservatory of Music where he still teaches.

In his spare time, he is still writing, although because of his age, he is being far more selective about what projects to take on, choosing only those he deems meaningful.

“My songs are full of emotions and patriotism,” He says.

One current composition is to commemorate the founding father of modern China, Sun Yat-sen; another is about the history of Jinggangshan, a city in the southwest of Jiangxi province known as the cradle of the Chinese revolution.

Despite being a prolific composer, none of his works has achieved the same level of fame as his signature piece. In previous interviews, He has expressed regret over this and blamed The Butterfly Lovers for eclipsing all his other compositions.

But these days, he is preoccupied with what he sees as a bigger problem – few, if any, good Chinese classical works have been written in recent decades. He thinks this is because contemporary Chinese composers are missing a very important point.

Is this Lang Lang 2.0? Chinese pianist returns to stage after injury

“You cannot write music to demonstrate your own capability,” He says, recalling the teaching he has taken to heart. “Music has to be written for the people.”

Celebration of the Yellow River 50th Anniversary, Butterfly Lovers 60th Anniversary, Singing “Ode to the Motherland” at Victoria Harbour waterfront, Avenue of Stars, Tsim Sha Tsui, Hong Kong, October 4, 8pm. Free admission