Xi Jinping set to sell International Import Expo as symbol of China’s openness and globalisation

- President will deliver a keynote speech to kick off the weeklong trade fair in Shanghai, which has attracted about 3,000 companies from around the world

- But while foreign firms are free to display their goods there, they’ll still face the non-tariff barriers that make it hard to sell them

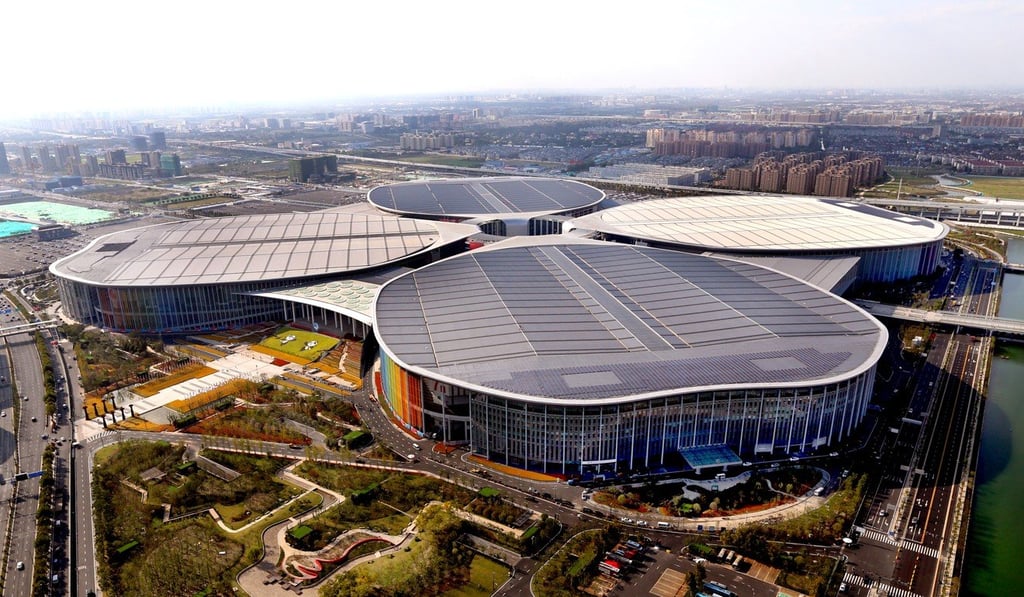

President Xi Jinping will seek to promote China as an advocate for globalisation and free trade on Monday when he officiates at the launch of the inaugural China International Import Expo in Shanghai.

He is expected to deliver a keynote speech to kick off the weeklong trade fair, which has attracted about 3,000 companies and traders from around the world, all of which want a slice of China’s massive consumer market.

Among them will be Peter Pan, a Chinese-American entrepreneur who runs a factory in southern California that makes personal care products. He is exactly the kind of businessman that warms US President Donald Trump’s heart, after selling his operations in eastern China about three years ago and relocating to the US.

But while Pan has rented 12 booths at the Shanghai trade fair to display thousands of his products, at the moment he cannot sell any of them in China.

Despite setting up a sales office in Shanghai last year, and beginning the process of registering 100 products – covering everything from detergents to cosmetics – as required by Beijing, not one of them has been approved. The process has so far cost him 1.5 million yuan (US$217,000).