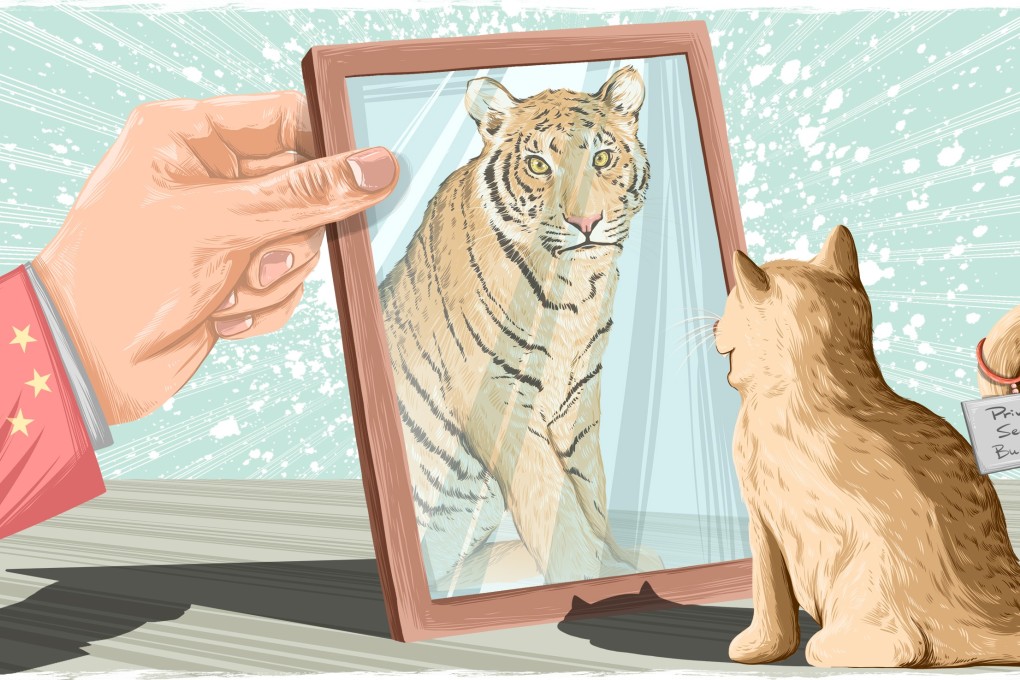

Can China’s leaders restore confidence to private businesses?

- China is rolling out a nationwide initiative to help private business owners but some question whether it will be able to take the necessary steps

- While the Communist Party has been happy to reap the benefits of burgeoning private sector, fears that ideology will trump pragmatism remain

China’s private sector, the driving force behind the country’s economic miracle over the last 40 years, is struggling amid the Chinese government’s campaign to reduce national debt and the trade war with the United States. This is the first story in a series that will detail the challenges private firms face and outline the government’s attempts to address them.

Some would say that Chinese President Xi Jinping rediscovered the private sector in his country this year out of necessity.

Facing a rapidly slowing economy because of the trade war with the United States, Xi and senior leaders of the ruling Communist Party have put on an unusually friendly face for the country’s private businesses since the summer, publicly acknowledging their struggles and promising to help.

But it remains to be seen whether the government will take the necessary steps needed to revive business confidence.

What is clear is that Xi and his government need the private sector, which accounts for about 60 per cent of country’s economic activity and 80 per cent of its jobs.

Without a strong private sector providing a stable economic foundation, Xi’s dream of a resurgent China could fade away.