Surprise, war and miscalculations, China’s turbulent economy in 2018 had it all and more

- The world’s second largest economy started the year with the strong intentions to improve the quality of growth but ended it hoping for a better 2019

- The trade war with the United States, the government’s deleveraging campaign to reduce debt and an unhappy private sector all played their part

If there is a single Chinese word to describe China’s economy in 2018, there may be no better one than gang, which translates to dispute and leverage.

Beijing started the year with the strong intentions to improve the quality of growth, vowing to reduce deeply troubling risks in the financial system and to control rampant pollution.

But in reality it was disputes – either between China and the United States, or with the Chinese private economy and state-owned enterprises – that dominated the headlines.

The world’s second-biggest economy is expected to achieve the government’s growth target of “around 6.5 per cent” this year, but the deviation from its original policy intentions, a mixed result of misjudgment, excess pride and uncontrollable external factors, have turned out to be very costly.

Unprecedented trade war

The Chinese government’s strategy of making major purchases of US products managed to prevent the US China-bashing from damaging bilateral ties in the first year of Donald Trump’s term as US president which began in January 2017, but that strategy was no longer effective in 2018.

“We were relatively slow to foresee [the US actions] … and underestimated [the Trump administration’s] determination. Also, policy support was not well prepared,” said Qu Fengjie, director of the external economy research institute under the National Development and Reform Commission.

“It’s not simply economic friction, but a turning point of bilateral ties and a strategic adjustment of the US,” warned Li Wei, an associate professor of international relations at Renmin University of China.

China’s lowest first-quarter growth rate was 6.4 per cent in 2009, meaning a drop below 6 per cent would represent a record low since the National Bureau of Statistics started publishing quarterly figures in 1992.

The government’s deleveraging campaign to cut excess debt and risky borrowing – one of the three major tasks laid out at the start of the year by the top leadership – sought to tackle the risk from the huge, and often hidden, debt accumulated in a decade of economic stimulus since the 2008 global financial crisis.

Risk from the deleveraging campaign

The country’s debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratio stood at 253 per cent of GDP at end of June, one of the highest rates in the world.

Beijing slashed its fiscal deficit ratio for the first time in six years, while a clampdown on shadow banking rippled to capital-thirsty private firms, local government controlled financing vehicles and public-partnership projects.

“Its impact on the economy has exceeded expectation upon a variety factors, most notably the trade war, a shadow banking curb and environmental protection,” Bank of Communications senior researcher Liu Xuezhi said.

“Particular, infrastructure investment has registered a free fall.”

The infrastructure investment growth, a major government tool in previous rounds of economic stabilisation, plunged to 7.3 per cent in the first half of this year, compared to 21.1 per cent a year earlier.

And despite the offsetting measures that started in July, the slowdown continued, with January-November growth of only 3.7 per cent.

Li Yang, a senior researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and a former policy adviser of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), said the deleveraging campaign was meant to avoid a financial crisis rather than exacerbate an economic slowdown.

“If it progresses too quickly – rather than having a controlled timing and pace in coordination with other policies – it could artificially create a Minsky moment or even Lehman Brothers moment,” he said.

Minsky and Lehman Brothers moments refer to the sudden collapse of a financial market or institutions, usually triggered by debt, currency or other issues.

The first is named after economist Hyman Minsky, while the second refers to the collapse of the US investment bank Lehman Brothers 10 years ago that rocked global stock markets and led to the biggest financial crash since the Great Depression.

A year ago, former PBOC governor Zhou Xiaochuan warned that China must stay alert for a Minsky moment.

After the first US tariffs were imposed on Chinese products in July, Beijing’s policymakers continued the deleveraging campaign even though they shifted the policy direction to economic stabilisation.

At the Central Economic Work Conference in December, the top leadership vowed to carry on “structural deleveraging”, paving the way for a bigger economic stimulus.

“It will become a long-term policy goal” rather than an immediate priority, Li said.

Structural deleveraging means structural changes among different sectors. For instance, the government can have higher leverage, but corporate leverage should be lowered, therefore the overall debt-to-GDP ratio will be kept roughly stable.

Private economy outcry

Private firms, the major victims of both financial deleveraging and the trade war, have been hit the hardest by the economic slowdown.

A total of 33 firms for the first time registered bond defaults by November 5, 28 of which were private firms, according to Everbright Securities, compared to only nine private firms in 2017.

In addition, dozens of private owners of listed firms risked losing their controlling stakes when the value of the shares they pledged to banks as collateral for loans fell with the rest of the stock market.

As well as the decade-old problems of lack of access to credit and high fundraising costs, the governments support of state-owned enterprises to become bigger and stronger and feelings of those who wanted to eliminate private ownership turned out to be the last straw.

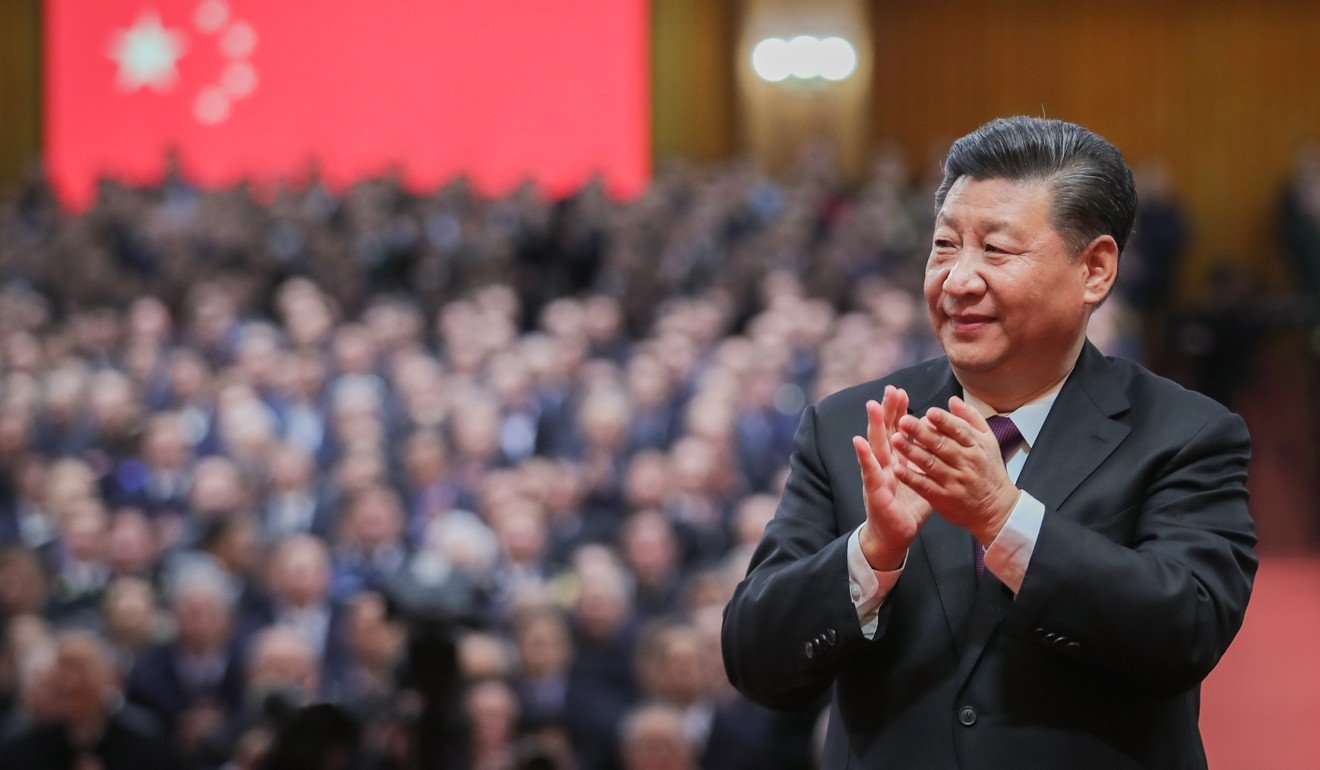

Xi also rolled up his sleeves at a high-profile symposium at the start of November.

“Some argue that the private economy has completed its mission and will fade out. All these statements are completely wrong and do not conform to the party’s policies,” he told dozens of private sector representatives.

Lu Feng, a professor of economics at Peking University, said the arguments of those advocating elimination of private ownership were not well formulated.

“However, they do expose some inconsistency between our ideology and the reform and opening up reality,” he said in December.

Lu said further reforms were needed to lower institutional costs and address the obstacles that businesses faced every day.

“Market access for private firms have been talked about for years, but many old problems remain unsolved,” he said.