Can China meet US trade war demands on IP theft and forced technology transfer?

- One of the primary demands from the United States is for Beijing to strengthen intellectual property protection and stop forcing the transfer of technology

- China has made some concessions, but still considerably lags Western markets on enforcement

This is the first article in a five-part series looking at US demands for structural reform in the Chinese economy. These demands are the named conditions for ending the trade war.

1. The US demand: intellectual property protection and an end to forced technology transfer

Foreign companies complain that China uses administrative tools such as foreign ownership restrictions, business licensing and product approvals to “coerce” the firms to transfer technology and intellectual property (IP) to Chinese entities.

This is often claimed to be the key to gaining access to a huge consumer market in a nation of 1.4 billion people.

Systemic IP theft in China costs US companies at least US$50 billion per year, according to a US Trade Representative (USTR) report published in April 2018, following an investigation under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974.

That was the legal basis for the US’ imposing a 25 per cent tariff on US$50 billion of Chinese imports starting in July last year and an additional 10 per cent tariff on US$200 billion of imports from September.

The US claims the Chinese government is coordinating an espionage campaign designed to capture cutting-edge technology to boost industrial policy. Outright theft of US IP is a key part of this strategy, the US argues.

In addition, the US said Beijing has strived for years to acquire US companies to obtain trade secrets and commercial information in key industries to gain a commercial advantage over US firms.

Some foreign businesses in China are still required to form joint ventures with Chinese companies, despite a recent relaxing of foreign ownership requirements in a few mature sectors. These joint ventures often require some level of technology transfer.

The US also charges that Chinese agents have physically broken into US corporate offices, while China and Chinese companies have repeatedly paid off corporate insiders at US and other Western companies to simply walk out the door with high-value trade secrets.

2. Case study: American Semiconductor

A settled case last year between the Massachusetts-based American Semiconductor (AMSC) and Chinese wind turbine manufacturer Sinovel sheds light on China’s alleged IP theft.

Through a Chinese subsidiary, AMSC had been providing electronic components that regulate power flows in wind turbines to Sinovel.

In 2011 AMSC discovered that the Chinese manufacturer had stolen the source codes of the control system by bribing an employee in AMSC’s Austrian subsidiary.

AMSC filed four lawsuits on trade secret and copyright infringement in China against Sinovel in 2011, but saw little progress for nearly two years.

In 2013, the US Department of Justice indicted Sinovel and charged it with theft of trade secrets.

Last July, Sinovel reached a settlement with AMSC, agreeing to pay a total of US$57.5 million to AMSC’s Chinese subsidiary and an additional US$850,000 to other victims.

Subsequently, a federal court in Wisconsin imposed a fine of US$1.5 million on Sinovel after concluding that AMSC’s losses from trade theft were more than US$550 million.

3. What is China doing to address this?

Until recently, Chinese officials have denied US accusations, arguing that technology was always transferred voluntarily and that there was no proof of any government involvement in the theft of trade secrets.

But in December, as part of the trade war truce, the US and China agreed to negotiate reforms to prevent forced technology transfer and protect foreign companies’ IP.

A total of 38 government agencies including the powerful National Development and Reform Commission, the People’s Bank of China and the National Intellectual Property Administration signed a memorandum in December to step up cooperation on punishing violations of IP rights.

According to the memorandum, those violating IP rights can be cut off from government funding, barred from government procurement, restricted in access to land and financing, or temporarily banned from importing and exporting.

China first established specialised IP courts in major cities and commercial hubs in 2014. Recently, a new IP tribunal was established at the Supreme Court level that will expand over three years to cover issues such as copyright, IP and unfair competition.

Beijing is in the process of revising its patent law that is expected to bring heavier penalties for violations and be connected it to the country’s social credit system, through which violators could be blacklisted and have restricted access to to things like flights and loans.

Unlike standard IP law, the patent law protects new inventions. Once granted, a patent gives investors the exclusive right to sell their invention for 20 years. It does not address forced technology transfer.

As China strives to become a leading global innovation centre, protecting IP is increasingly important, irrespective of US demands, said Cedric Lam, head of IP for China at law firm Eversheds Sutherland.

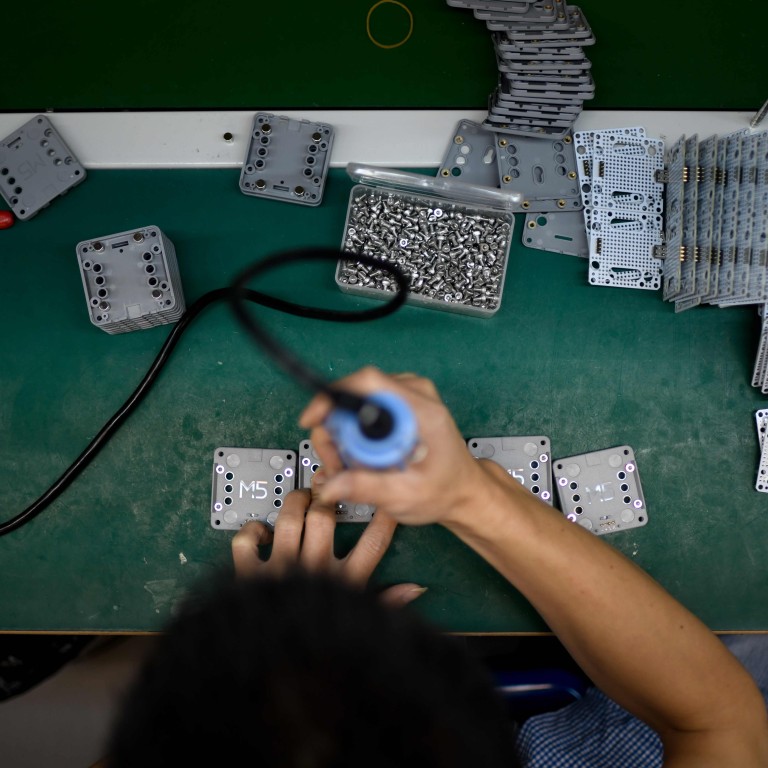

As it encouraged individuals to innovate, China saw a surge in patent applications.

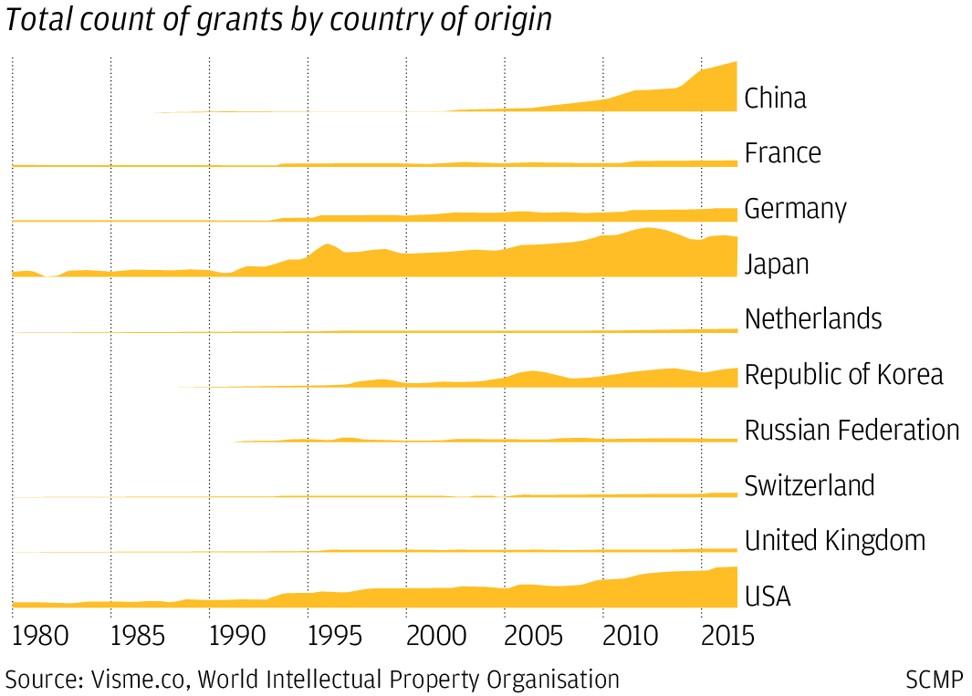

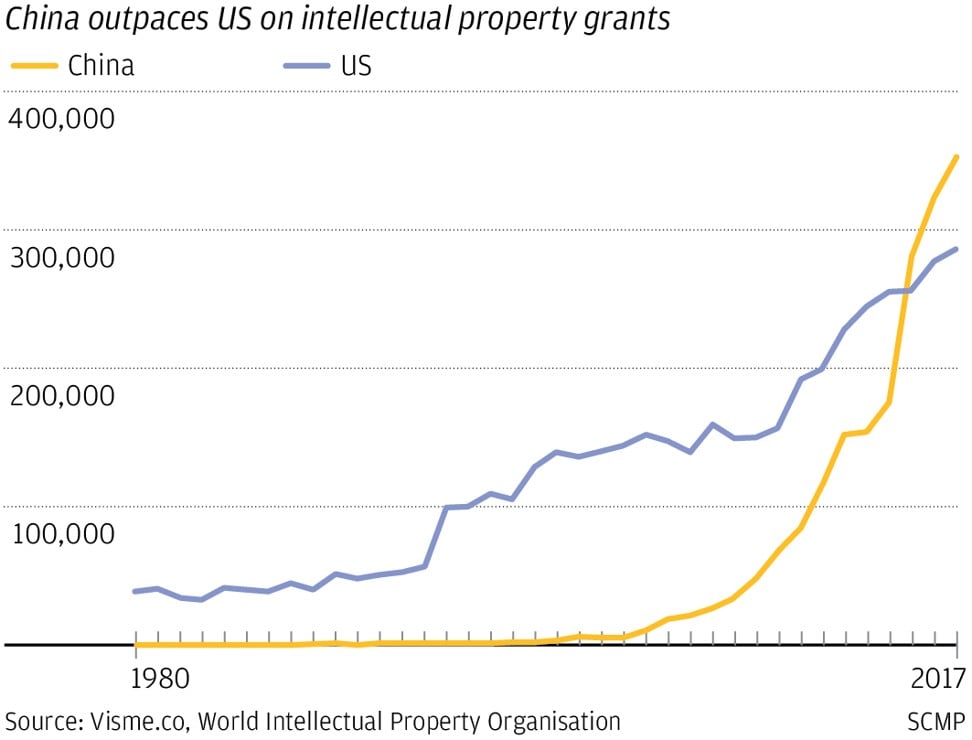

Between 2005 and 2010, patents granted in China rose from 21,575 to 352,560, even though a large number of the patents ended up being abandoned, according to data from Visme.co and the World Intellectual Property Organisation.

The period also saw a huge surge in IP cases, with China now the world’s most litigious nation, in IP terms.

Foreign plaintiffs were more likely to win and receive injunctions than their Chinese counterparts, said Jason Rantanen, a law professor at the University of Iowa.

Damages awarded to foreign patent owners averaged 201,620 yuan (US$32,837.21), almost three times higher than those awarded to Chinese patent owners at 66,217 yuan (US$9,900).

Beijing is now also fast-tracking a foreign investment law that had been languishing for years. The government is seeking public opinion on stopping government officials from using administrative means to force technology transfers.

4. Chances of meeting US demands

It has been reported that the outline of a deal is in place, covering structural issues in the Chinese economy. Among these are IP theft and forced technology transfer.

The further opening up of China’s hi-tech and car sectors could negate the need for joint ventures, helping to resolve some concerns on these demands.

However, Beijing remains reluctant to tighten enforcement of its IP and forced technology transfer laws, in case it hinders economic development, said professor David Ahlstrom at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

“Many people take for granted that the US is a leading IP rights champion and China a leading violator. Yet as recently as the 19th century, the pirating of British and foreign publications such as books, and entertainment such as plays, was widely practised by Americans,” said Ahlstrom.

“We predict that to the same extent that the US voluntarily agreed to strengthen IP protection when the US economy became sufficiently innovation-driven, so China will similarly enhance its IP protection,” Ahlstrom said.

Still, without introducing serious punitive sanctions, the strength of many of the measures China has taken remain in question. China still has a long way to go to reach Western standards.

Under Chinese law the maximum fine for violation is 5 million yuan (US$744,210), but the average award is only 190,000 yuan (US$28,000), not enough to deter violations, Ahlstrom said.

One way of ensuring China complies would be to force state-owned enterprises to purchase products directly from foreign manufacturers rather than require items to be produced in China, said Steve Dickenson, a trade lawyer at Harris Bricken.

However, the US will face a challenge determining which forced technology transfers involve the Chinese government. Further complicating the matter is that many Chinese executives, in both the private and state sector, are appointed by the government, Lam added.

Part two of this series will look at US demands for market access in China.