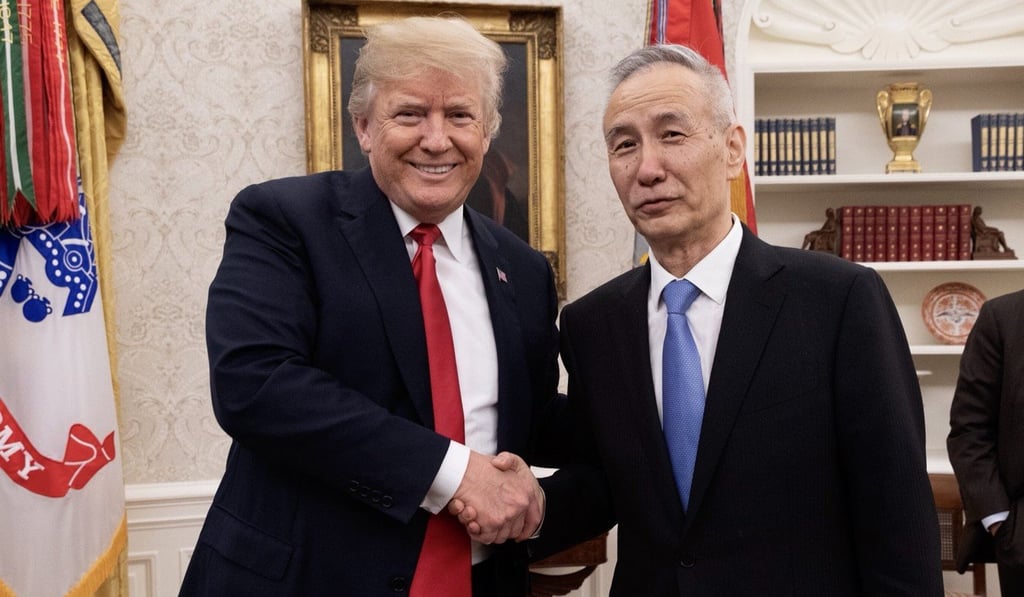

‘No second choice’: Liu He, China’s man on the front lines of the trade war talks with the United States

- China’s English-speaking vice-premier, special envoy and chief trade negotiator is President Xi Jinping’s top economic aide who is respected the world over

- The 67-year-old was in Washington last week for the latest round of talks with US negotiators and President Donald Trump

Nine months ago, Liu He, the top economic aide to President Xi Jinping, told state media that China and the United States had agreed during talks in Washington not to fight a trade war.

His words were short lived, as only a few days later US President Donald Trump unexpectedly decided to impose trade sanctions on China and start a prolonged economic battle between the world’s two largest economies.

Last week, Liu, carrying the title of special envoy in addition to those of chief trade negotiator and vice-premier, was again in Washington for continued talks to put an end to the seven-month-old tariff war that has shaken global economic confidence.

In addition to pledges to buy more American products from soybeans to natural gas, China is expected to offer compromises on a number of structural issues that could curtail the government’s involvement in China’s domestic economy.

An agreement to end the trade war will be a major feather in Liu’s cap, but more important to his reputation, and to the future of his country, will be his ability to shepherd through the changes in the economy required by the deal.

Liu, 67, spent most of his career as an economic adviser working behind the scenes, but in recent months has become one of the most closely watched figures by global investors and policymakers alike.