China’s ‘two sessions’: an economic watershed or just more of the same?

- Future of the economy to be prime topic at meetings of the National People’s Congress and Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference

- Some 3,000 of China’s most powerful officials and political elite will gather in Beijing over the next two weeks amid the backdrop of the US-China trade war

China’s annual gathering of its legislative and political advisory bodies – known as the “two sessions” – is one of the key events in the country’s political calendar and provides a rare opportunity for observers to get close to its movers and shakers.

This year’s meetings come as China continues to fight a trade war with the United States and battle the headwinds of an economic slowdown. They also mark 12 months since Xi Jinping amended the constitution to remove a presidential term limit and arrive as the nation prepares to celebrate 70 years of Communist rule.

In the third of a three-part series about the key issues facing this year’s “two sessions”, we look at economic challenges China and Xi have to face.

History may record that this year was a watershed for China, when Chinese leaders started taking the steps to change course and remove the structural obstacles to the country’s further development to become the world’s largest economy.

Or it may show leaders stayed their course, with the Chinese economy continuing to muddle along, trapped by its unwillingness to set its “animal spirits” free.

The meetings of the “two sessions” – the National People’s Congress (NPC), the country’s parliament where major policies are ratified, and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, the government’s top political advisory group – could give strong evidence over the next two weeks of the direction China’s leaders will choose.

With increasing headwinds buffeting the Chinese economy, some 3,000 of China’s most powerful officials and political elite will gather in Beijing to confront the dilemma between supporting near-term growth and undertaking the economic restructuring necessary to complete the shift to sustained, domestic demand-led growth.

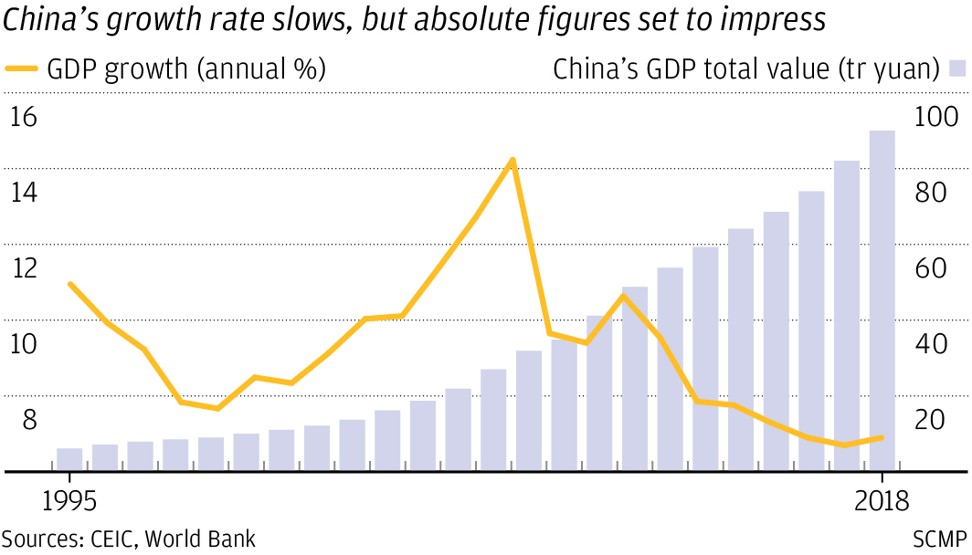

By anyone’s estimate, China has performed an economic miracle in the last 40 years, transforming from a backward, rural country into the second largest economy in the world.

Its massive stimulus response to the global financial crisis of a decade ago helped save the world economy.

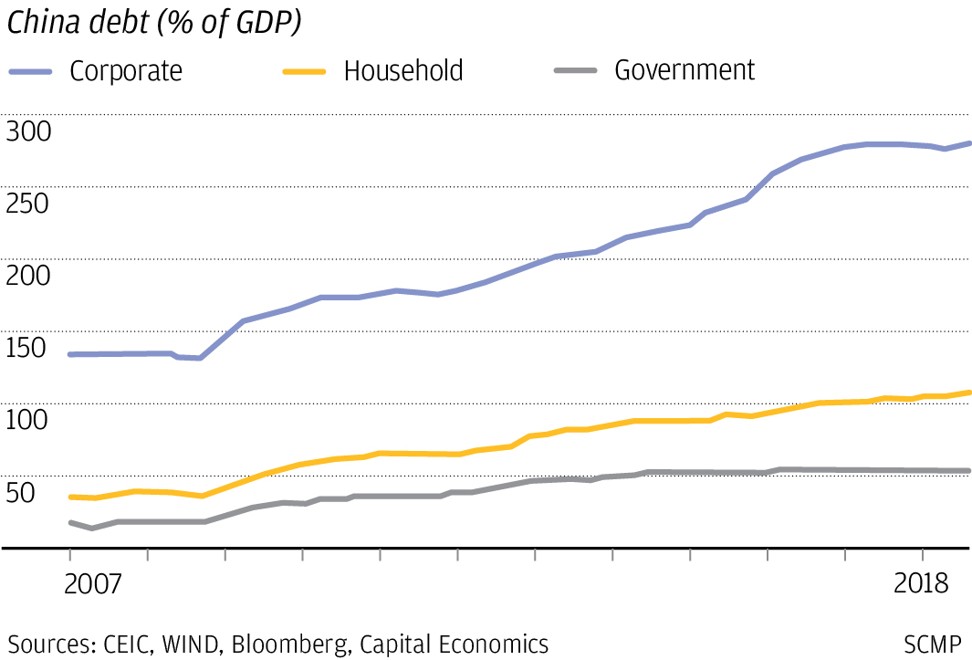

But the imbalances created by the Chinese model – a widening wealth gap, a huge pile of debt, overcapacity in industries, inefficient infrastructure spending and lack of financing for the private sector – have come into sharper focus under pressure of the US trade war, raising the question of whether the economy can evolve to the next level – higher value-added production and consumption-led growth – without major and deep structural changes.

These possible changes and how much China can afford to give up near term growth in exchange for long-term sustainable development could be major subjects of debate at the two sessions meeting.

“China’s restructuring has entered a crucial period where the long-term and pent-up structural issues are coming head to head with the cyclical problems stemming from changes [in the economy], raising the pressure and difficulty in macro control, and weakening the consumption drive,” said National Bureau of Statistics deputy director Sheng Laiyun last month, according to state media.

The meetings may also offer more details on how Beijing will strike the balance between controlling the growth of debt and the need to expand lending to spur growth.

It could also send a message to the world on how it plans to open up the economy further, in particular in response to requirements of any trade deal with the United States.

Premier Li Keqiang’s work report, due to be delivered Tuesday, is expected to set a growth target range of 6-6.5 per cent for this year, lower than 2018’s “about 6.5 per cent” target and necessary for the government to meet its goal of doubling the size of the economy in the decade to 2020.

Morgan Stanley economists said last week that they expected the NPC to adopt the same pro-growth easing stance seen since the Central Economic Work Conference in December, and announce more easing measures, particularly from the fiscal side.

These potentially include allowing more issuance of local government bonds to fund additional infrastructure spending and a cut in the value-added tax rate to help businesses.

A reduction in the social security contribution rate, a large cost for small businesses, is also possible.

“The government work report is likely to give more guidelines regarding opening up of domestic markets and [intellectual property rights] protection,” the Morgan Stanley economists wrote.

The meetings could also debate the solutions that China will offer to conclude a deal to end the trade war with the US, including addressing American accusations of unfair trading practises such as allegations that Chinese companies have stolen intellectual property from US firms through forced technology transfers and cybertheft.

To arrest eroding foreign investor confidence amid pressure from the US to reform the economy, China has rushed through a foreign investment law that aims to expand the scope of opening up the economy, and it is expected to be passed by the NPC this month.

It covers many of the items on the US wish list of structural reforms, including prohibiting forced technology transfers and better protection for intellectual property rights.

“We might see a further liberalisation of foreign ownership limits in some sectors announced during the NPC,” said Carlos Casanova, Asia-Pacific economist for trade credit insurer Coface.

“However, this will not be sufficient to offset the shift [of China production] towards other Asian emerging markets that has been taking place for quite some time; and which will be expedited as a result of ongoing tensions with the United States.”

Casanova said Chinese companies would have to rely less on foreign direct investment for technology transfers that have helped the economy expand over the past four decades.

Foreign direct investment into China rose just 3 per cent to US$135 billion in 2018, against the 7.9 per cent rise the previous year.

Overseas acquisitions of foreign technology assets, he predicted, would also be limited in key North American and European markets, where there are claims that Chinese technology giant Huawei has engaged in technology theft and that its technology poses a national security threat.

“The impact from the changing US-China relationship is in both the short term and long term: in the short term the focus is trade but in the long term it is more about technology and China’s ability to move up the value chain,” said Chen Long, China economist at Gavekal Dragonomics.

China and the US have so far avoided a further escalation of the trade war, and expectations that a deal will be signed when Xi meets US President Donald Trump in Mar-a-Lago later this month are high.

Complaints that the Chinese government’s excessive backing for the estimated 150,000 state-owned enterprises (SOEs) – from cheap loans to direct subsidies – have created a distorted market place, do not just come from the US and other Western nations.

The government is now looking at China’s own private sector, which enjoys little to none of the state’s preferential treatment, as a lifeline to prevent the economy from continuing to slow.

Listed state firms, according to Haitong Securities, enjoy twice the amount of government subsidies than listed private firms despite all private companies accounting for 60 per cent of economic output and 80 per cent of employment in the country.

Xi has vowed unwavering support for private firms, but at the same time, has continued to support SOEs as the economic backbone of the party’s control.

Private firms are now required to allow the party to establish branches inside each company, which may influence important business decisions. Critics see this requirement as a major step backwards.

How far China is willing to go to enact the structural changes to its system that are necessary to level the playing field for private firms, both domestic and foreign, remains in question.

“Xi, despite being a strong figure, does not seem to have the political will or capacity to tackle these economic issues head-on,” said Lynette Ong, associate professor of political science at the University of Toronto.

“His power base comes from the red aristocrats (princelings) who have major stakes in the SOEs and protected sectors.”

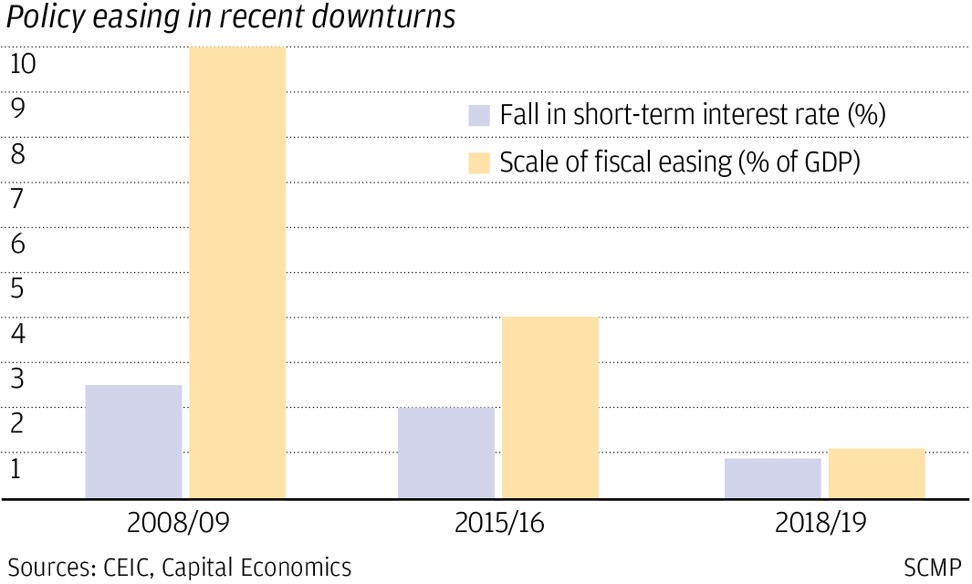

Since late 2018, Beijing has once again drawn on its well-trodden growth model – enact monetary and fiscal stimulus whenever the economy slows.

Between December and January, the National Development and Reform Commission, the nation’s state planning agency, approved 16 infrastructure projects worth 1.1 trillion yuan (US$164 billion), compared with just seven projects valued at 105.8 billion yuan between December 2017 and January 2018.

Banks extended a record 3.23 trillion yuan (US$481 billion) in new loans during January, almost triple the amount in December, as the national deleveraging campaign to reduce risky lending was largely shelved.

But the stimulus moves have so far yielded little as the economy slowed further in February as the official purchasing managers’ index primarily tracking manufacturing activity of state firms fell for a third straight month to 49.2, below the 50-mark that separates growth and contraction.

Growth in activity in the non-manufacturing sector, which includes services and construction, also slowed, with the sector index dropping to 54.3 in February from 54.7.

China’s ability to carry out further reforms and when it can put a floor beneath growth, which a number of economists predict the earliest to be in the second half of 2019, will be closely watched.

“The government says a lot of the right things but implementation has been difficult, and there should be a further push for reforms to increase pressure to make SOEs more efficient and close the companies that are not efficient,” said Danske Bank’s chief economist Allan von Mehren.

“Making a level playing field for Chinese private enterprises as well as foreign enterprises is key.”

That means having a single commercial law covering state owned and private firms, as well as foreign companies, said Alicia Garcia Herrero, Asia-Pacific chief economist for Natixis.

“Politics and the continuation of the regime is behind the delay in the reforms,” she said.

Even as the broad-based slowdown in the domestic economy continues, there are pockets of growth that will steer the country toward real sustainable expansion if nurtured with the right reforms, analysts said.

Consumer spending in smaller cities is rising at a double-digit rate, and although small in absolute terms compared to major cities like Shanghai and Beijing, they will drive China’s future demand and growth.

The country is also the world’s biggest market for e-commerce, mobile payments and industrial robots, with 800 million internet users, twice the number in the US.

It also has built world-class tech giants – internet gaming and payment firm Tencent Holdings, drone maker DJI, search engine firm Baidu and e-commerce company Alibaba Group Holding, owner of the South China Morning Post.

Bocom International research head Hong Hao said the trend towards a slowing in the economy has been evident for several years, given that consumption, which is tied to income growth, now accounts for 60 to 70 per cent of the economy. “Therefore, you have to shift into slower gear”.

The economy is maturing, but is not yet in a crisis, he said.