US-China trade decline leads to 20.7 per cent plunge in China’s total exports in February

- China imported 19.9 per cent less from the United States last month and exported 14.1 per cent fewer US goods, suggesting that the US-China trade war is biting

- Front-loading to avoid anticipated tariff rises and Lunar New Year holiday possible factors as exports post largest percentage drop since February 2016

China’s exports crashed by 20.7 per cent in February, the largest drop in three years, led by a large fall in trade with the United States.

The total export decline was much greater than expected, possibly providing the first evidence of the impact of US tariffs on Chinese goods.

China imported 19.9 per cent less from the US last month, down to US$7.9 billion from US$9.2 billion in January.

It also exported 14.1 per cent fewer US goods, suggesting that trade between the world’s two biggest economies is beginning to slow.

The total export drop will add to fears over a widespread economic slowdown and the effects of the US-China trade war on China’s economy.

In a poll of analysts by Bloomberg, the median forecast was for a 5 per cent decline in exports in February.

Imports also shrank significantly, showing a 5.2 per cent decline according to data released on Friday, much greater than Bloomberg’s poll, which predicted a 0.6 per cent slump.

China’s overall trade surplus narrowed massively in February, down to US$4.1 billion from US$39.16 billion in January, well below the forecast of US$26.2 billion.

China’s trade data were better than expected in January, largely due to front-loading of exports before the Lunar New Year Holiday that started on February 5, 10 days earlier than the previous year. But the February data showed the biggest decline in China’s exports since February 2016.

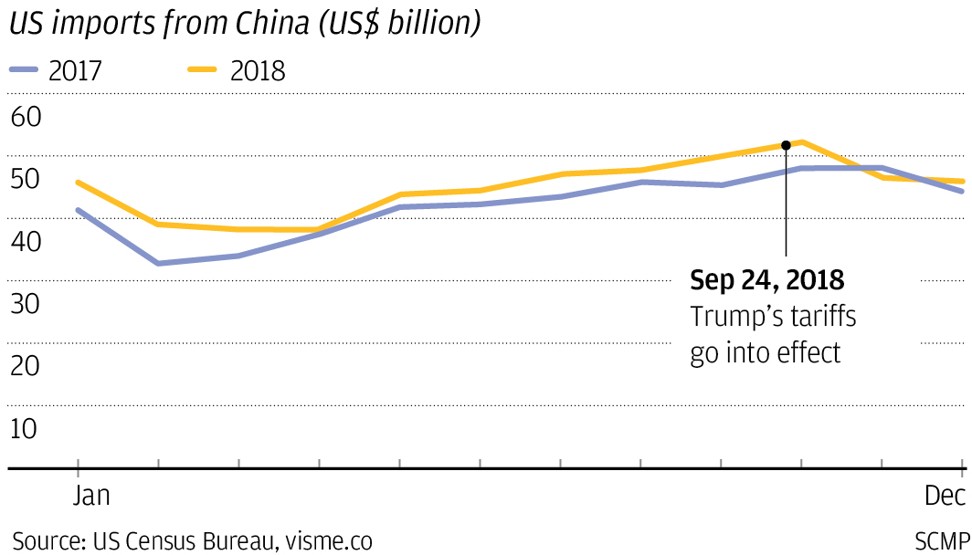

Chinese exports had continued to rise late last year as companies rushed to ship US orders before the expected rise in the tariff rate originally scheduled for January 1. But the fact that orders for early this year have been largely filled may have helped push down exports in February, coupled with the Lunar New Year holiday, when economic activity slows sharply.

“While there are the usual caveats that this is typical of the January and February seasonal factors, there’s always a bit of a slump, there is a wider trend towards slowdown in exports. This is something that we’ve been saying for a while: there’s a cyclical downturn and it is related to slowing global demand,” said Carlos Casanova, Asia-Pacific economist at Coface.

March data will be closely watched for further evidence of the impact of the US tariffs.

The data rounds off a week of poor trade data from both the US and China, suggesting that both economies are suffering from their tariff war, but also a slowing global economy.

“Tariffs are weighing on shipments to the US. But broader weakness in global demand means that, even if [US Presidnet Donald] Trump and [Chinese President] Xi [Jinping] finalise a trade deal soon, the outlook for exports remains gloomy,” said Julian Evans-Pritchard, China economist at Capital Economics.

We’re at the end of peak growth in the US, the European Central Bank has cut its growth forecasts, this is all bad for China. It all adds to the trade war, but we have not felt the full effect of that yet.

On Wednesday, it was announced that the US’ trade deficit for 2018 had widened to its highest point in a decade.

“Trade wars are good, and easy to win,” US President Donald Trump tweeted in March last year, but evidence is mounting up that this is not the case.

The trade deficit is the metric for which Trump went to commercial war with China, and on that front at least, he appears to be fighting a losing battle. The US’ 2018 trade deficit with China was US$419.2 billion – the highest on record.

In broader terms, while Trump pledged to level the US trade balance, the total national trade deficit has risen by US$100 billion since he took office and now sits at US$621 billion.

Within this, the 2018 goods deficit of US$878.7 billion was the highest on record. US Census data shows that in 2018, the country imported more cars, consumer goods, food and beverages than ever, despite Trump’s plans to bring manufacturing back to the US.

American exports still grew in 2018 – by 6.3 per cent – but just not as fast as imports, which rose by 7.5 per cent. The increase in imports is partly attributable to a resolutely strong overall economic picture in the US.

Economic growth dipped to 2.6 per cent in the final quarter of 2018, but this is still stronger than most other major Western economies. It also shows the effects of a strong dollar and a weak yuan, which has been devalued over the course of the eight-month trade war.

For US buyers, foreign goods – including Chinese products – are cheaper to buy, while for everyone else, however, US goods are more expensive.

This compared with January when Chinese imports of US products plunged 41.1 per cent from a year earlier to US$9.2 billion last month, the lowest since February 2016, according to data released by the Chinese General Administration of Customs.

High among them are mounting debt, slowing investment growth and consumer spending, with car sales in China falling for the first time since 1990 last year.

Both Beijing and Washington are under pressure to seal a deal to end the trade war. It has been widely reported that a deal will be reached before the end of March which would likely see China make large scale purchases of US goods in return for a removal of tariffs.

Manufacturers in the US are also beginning to show the scars of the trade war. In a report released this week by the Ohio Manufacturing Institute, many of the state’s producers showed “very negative” impact from the tariff battle.

“One-third (169) of the respondents were either very negatively or negatively affected, and only 18 establishments, or 4 per cent of the 493, indicated that the tariffs had been either very positive or positive in their impact – a ratio of harm to benefit of nearly 9:1 of extreme harm to extreme benefit was nearly 14:1,” the report read.

“If [the tariffs] come in on automobiles, you will see a pretty big disruptive effect,” Koopman said.

“It will increase some [US] domestic activity, but at higher costs and less choice. Consumers will be worse off, some domestic workers, companies might gain, others will lose.

“The net effect could be relatively small. Bigger challenges could be firms saying: ‘I don’t know what to do with my next investment.’ Consumers like: I don’t know if I should buy a car now, because auto supply chains are complex, I might lose my job’.”