China’s private tutoring industry is booming despite economic slowdown

- Estimates of the size of annual revenues in the private education sector vary from 1.6 trillion yuan (US$238 billion) to 2.68 trillion yuan from Deloitte

- Online education market was valued at 251.7 billion yuan (US$37 billion) last year and will reach 380.7 billion yuan in 2020, consultancy firm says

Amid China’s economic downturn, its booming education industry has become a bright spark in the gloom thanks to surging demand for after-school learning, resulting in an influx of investment capital.

Within the rapidly expanding private education sector, the fastest growth comes from after-school tutoring, such as private tutoring and English instruction classes as Chinese parents have no qualms about spending on such programmes to help their children.

“Parents can cut [other] discretionary spending, but they would never compromise on the education of their children,” said Anip Sharma, partner at management consultancy firm L.E.K. Consulting.

Such recession-proof spending on education is a component of the broader services industry that Beijing is counting on to offset the economic blow from the shrinking of traditional manufacturing industries compounded by the fallout from the US-China trade war.

Estimates of the size of annual revenues in the private education sector vary among industry experts, from L.E.K. Consulting’s 1.6 trillion yuan (US$238 billion) to audit and advisory firm Deloitte’s 2.68 trillion yuan. On the back of a compounded 10.8 per cent annual growth trajectory, the market could reach a value of as much as 5 trillion yuan (US$744 billion) by 2025, according to Deloitte.

That beats the pace at which the public education sector, run by the Ministry of Education, has grown. According to research firm Frost & Sullivan, citing data from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) and the education ministry, public education grew at a compound annual rate of 8.4 per cent between 2014 and 2017 to 4.19 trillion yuan (US$624 billion). Government spending on public education is about 4 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product.

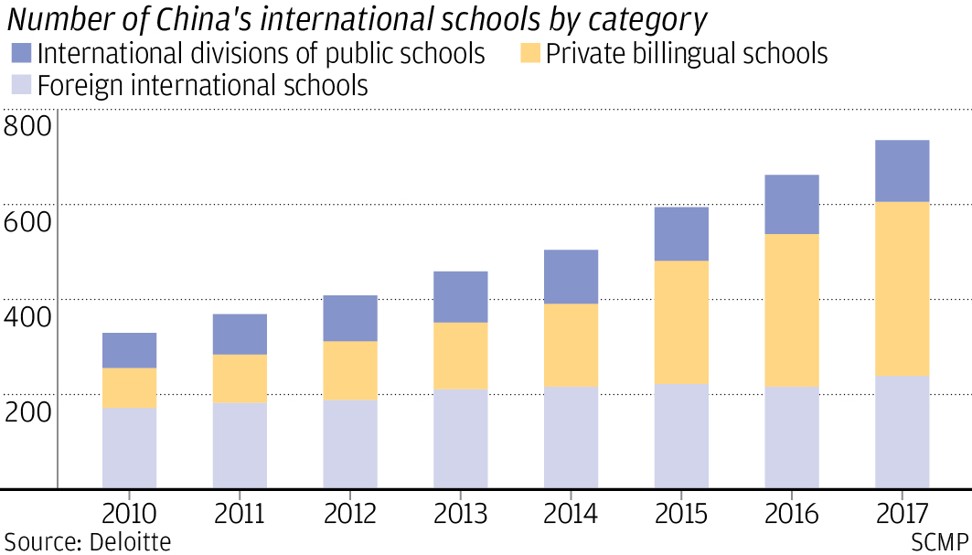

China opened the industry to private investors with the introduction of the “Outline for Education Reform and Development” in 1993, with numerous foreign operators entering the market over the following decade. As a result, the number of international and private schools in the country more than doubled to 734 between 2010 and 2017, according to Deloitte.

The private education sector has expanded in tandem with economic growth and affluence, underpinned by a devotion to child education that increasingly includes the adoption of diverse interests outside the traditional exam-oriented curriculum, or after-school tutoring, which has led to a 433 billion yuan (US$64 billion) market segment that market research company Frost & Sullivan has projected will increase to 500 billion yuan next year.

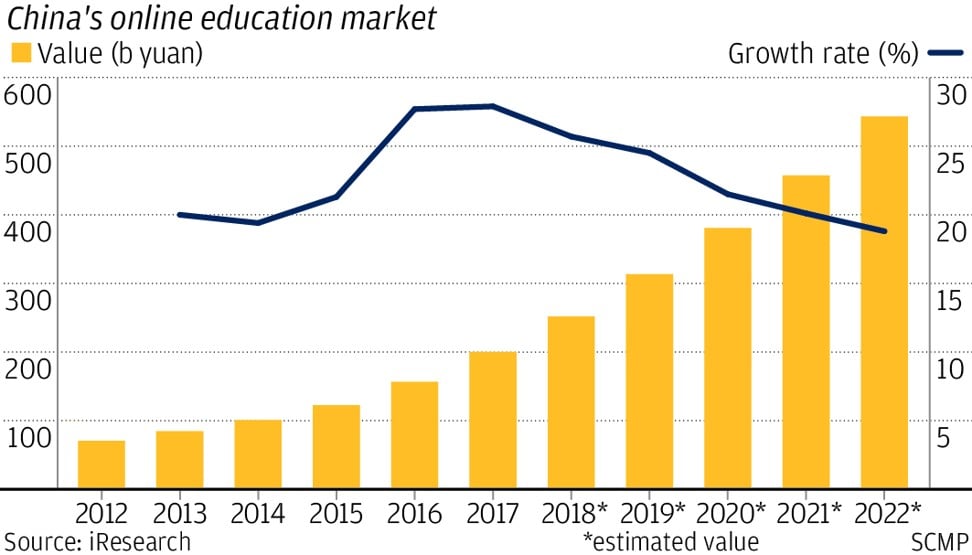

In particular, online education has taken off rapidly from 2013, according to China-focused consultancy firm iResearch, and is set to maintain an estimated 20 per cent growth rate in the next few years. The online market was valued at 251.7 billion yuan (US$37 billion) last year and will reach 380.7 billion yuan in 2020, iResearch said.

Online education in the past few years has been the major growth spot.

Eric Yang, CEO of iTutorGroup, one of China’s biggest online education firms, forecasts that the current 5 per cent market share that online platforms cover of the private education sector will jump to 50 per cent in the next three to five years.

“Online education in the past few years has been the major growth spot,” he said, adding that traditional bricks and mortar school operators are transitioning or expanding to online platforms to capture a growing market fuelled by demand from parents who like the benefits of the online learning format.

These include the flexibility on scheduling when lessons are conducted as well as the ability to customise the content of the lessons, leveraging artificial intelligence, to suit the child’s learning pace and existing knowledge, Yang said.

Education companies estimate that education expenses take up anywhere from 20 to 50 per cent of an average family’s disposable income. After-school classes – from music lessons to English instruction and supplementary tutoring for a school curriculum – are now staples in a child’s routine, particularly those from China’s burgeoning middle-class, which totals nearly 400 million people, according to the NBS. The World Bank defines members of this group as anyone earning an annual salary of between US$3,650 and US$36,500.

Beijing is also banking on this group to generate domestic demand as it enacts much-needed structural reforms to complete the transition from export and investment-led growth to a consumption-driven economy and narrow the regional wealth gap as growth in the larger cities tapers off.

“Chinese people value education and so whether the economy is growing or slowing, it will not affect [education spending] so much,” said Jin Lei, founder of online English-language teaching platform Magic Ears.

“During the past 30 years of China’s development, we have also come to realise how education can change a person’s life.”

Most of the online platforms grew their business primarily in the largest, tier 1 cities, but have since had faster growth in smaller tier 3 and tier 4 cities, said Sharma from L.E.K. Consulting.

“Half of the [online] segment’s growth comes from tier 3 and tier 4 cities. Many of these platforms are creating the market,” he said.

Yang from iTutorGroup said while his company’s growth in tier 1 cities was a strong 20 to 25 per cent annually, the increase in tier 2, tier 3 and tier 4 cities was a staggering 80 per cent on an annual basis.

The greater demand in China’s smaller cities is due to a lack of institutions and teachers of the same quality available in Beijing and Shanghai, according to Xiao Dun, founder of 17zuoye.com, one of China’s largest homework platforms for children aged between four and 19 years old. Xiao added that 50 per cent of the 17zuoye.com’s users come from tier 3 and smaller cities.

“We see the opportunity … in pairing technology with education; so more people can benefit from a good education, it’s a question of fairness in education,” said Xiao.

But that is not to say traditional offline education companies find themselves in a diminishing role. Operators like Beijing-based Ivy Education Group, which runs schools in cities like Beijing, Chengdu, Tianjin and Ningbo targeting the premium education segment, are also expanding their reach.

Half of the [online] segment’s growth comes from tier 3 and tier 4 cities. Many of these platforms are creating the market.

Ivy’s CEO and founder Jack Hsu said they would open their first school – a kindergarten for children aged around four to sevens years old – in Shenzhen in September.

Hsu sees the age group as the fastest growing segment in which “we do not see a ceiling” with demand increasing 20 to 30 per cent annually.

“It depends on how fast approvals [from authorities] are given. The pressures and bottlenecks are on the supply side,” he said.

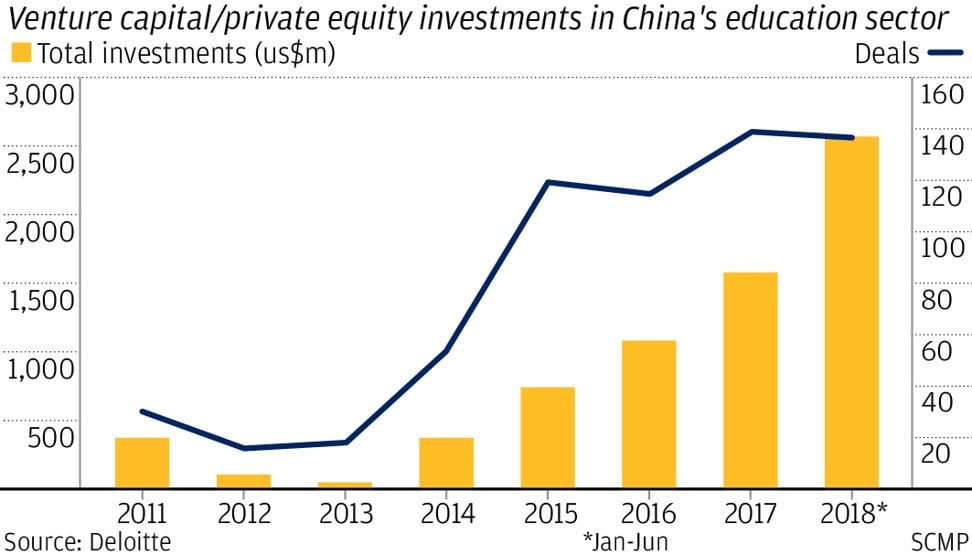

Investors agree, as there has been no shortage of capital inflows into the sector over the last decade. Venture capital and private equity investments grew from US$382 million in 2011 to US$2.57 billion in the first half of 2018, according to Deloitte.

Listed Chinese education companies in the United States and Hong Kong have also been sought-after targets, propelling them to become the world’s largest education firms by market valuation. TAL Education Group and New Oriental Education led the pack in 2018, valued at US$17.7 billion and US$11.3 billion, respectively, according to L.E.K Consulting.

Still, the industry is not without its problems as the last year has shown as some segments lost their shine following scandals, including child abuse allegations at US-listed RYB Education, which led the central government to tighten controls.

In August, China published draft regulations on support for private schools according to categories and standardisation of after-school tutoring entities for public consultation, and announced a ban on kindergartens raising funds in capital markets for a few months.

DBS analyst Dennis Lam said the restriction on fundraising should come to an end when implementation details of the new regulations are released later this month. With China’s two-child policy and parents’ willingness to pay for education, Lam described the industry as an “attractive high-growth sector [whose stocks are now] trading at a depressed valuation”.

But there is also speculation that authorities may strengthen its oversight on the booming online segment.

Last week, The Wall Street Journal reported that online platform VIPKid has put hundreds of its mostly American teachers on notice for using certain maps that did not align with China’s education standards when teaching Chinese students, and severed the contracts of two teachers for discussing Taiwan and Tiananmen Square in ways that went against China’s preference.