As trade war continues, are the US and Chinese economies heading for a messy divorce?

- Separation is under way in manufacturing, technology and investment, and while it predates the trade war, the Trump tariffs have acted as turbo-boosters

- Unconfirmed reports that Apple may move part of its manufacturing out of China fuel suspicion the two nations will increasingly go their separate ways

This is the first of four stories examining important issues ahead of the meeting between Chinese President Xi Jinping and US President Donald Trump at the G20 leaders summit on June 28-29 in Osaka, Japan.

Like many Americans who manufacture in China, Daniel Krassenstein will be watching President Xi Jinping’s meeting with US counterpart Donald Trump on the sidelines of the G20 meeting in Osaka next week very closely.

Procon Pacific, Krassenstein’s company, makes 40 per cent of its industrial packaging products – “super sacks or bulk bags that can store anything from sugar milk powder to dangerous chemicals to fertiliser to mixed cement, you name it” – in China.

A few years ago, almost all of its products were made in China, initially in Changzhou, Jiangsu province. But as costs rose, it moved some production to the northern province of Shandong, where it could source cheaper land and labour through its Chinese partners.

“This had nothing to do with Trump, or the trade war, it was purely due to labour costs and the cost of compliance impacting China in general. But in this case it started hitting Shandong province, which was our sweet spot for our lower-end bags,” said Krassenstein, the company’s global supply-chain director.

The company’s products are subject to an 8.4 per cent import duty when sold to companies in the United States, no matter where they are made. However, if Trump adds 25 per cent tariffs on US$300 billion worth of goods made in China, in what is the next potential tariff rise, it would push it to 33.4 per cent.

“The concern is what happens 12 months down the road, especially when you get into the US election season and Trump plays the China card to get more votes. Frankly speaking, I think while there might be a temporary truce with a small [tariff] increase, I'm more concerned with what happens next summer.”

The concern is what happens 12 months down the road, especially when you get into the US election season and Trump plays the China card to get more votes

This supply-chain shift is a simple example of what many are terming the wider phenomenon of US-China economic “decoupling”. The trend predates the trade war, but the tariffs have acted as turbo-boosters. Now, what was regarded a year ago as a fringe view on the extreme edges of the Trump administration is at the crux of mainstream conversations.

“I think that to the extent it is possible, it is going to happen. Business hates uncertainty, business does not want to be caught in the middle of political conflict. Business wants to find a stable environment. And so anyone that can move will move,” said Jeff Moon, a public affairs consultant who was assistant United States trade representative (USTR) for China during the Obama administration.

Chen Li, an assistant professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, refers to the split as a “Balkanisation of supply chains”.

“If politicians want, they can always break the global market, right? But I don't think it's going to get that bad yet,” Li said.

While low- to medium-end manufacturing is relatively simple to disentangle, there are chasms and barriers appearing all over the US-China economic relationship, suggesting that a broad-based break-up may be under way, even in more complex sectors.

Early in June, US Senators Marco Rubio, Bob Menendez, Tom Cotton and Kirsten Gillibrand introduced legislation which, if passed, would “increase oversight of Chinese and other foreign companies listed on American exchanges and de-list firms that are non-compliant with US regulators for a period of three years”. The implication is that Chinese companies that are not transparent would be banished from US financial markets.

The decoupling of investment is already clear. Last year, Chinese acquisitions of American companies plunged 95 per cent from their peak in 2017 after the US Congress gave the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US authority to broaden the scope of its reviews of Chinese acquisitions on national security grounds.

Add in the increasingly messy US-China technology rivalry after the US blacklisted Huawei, cutting China’s technology giant off from many of its important suppliers, while Washington aggressively lobbies other nations to ban Huawei equipment from their 5G networks.

Beijing, in turn, reportedly summoned US technology firms, including Dell and Microsoft, to warn them against cooperating with the blacklist, then formed a register of its own. The list of “unreliable” foreign entities singles out those deemed to have damaged the interests of Chinese firms and shows how deep the cracks in the relationship are becoming.

This week came the news that Apple was considering moving 15 to 30 per cent of its production out of China. The story by the Nikkei Asian Review followed claims last week from an executive at Foxconn, which assembles iPhones and iPads for Apple in China, that it had sufficient capacity in other countries to produce all US-bound Apple products, but some experts are sceptical.

“Apple has probably invested more in a China-centric supply chain than any successful company in recorded history. To just presume that they can jettison everything they have achieved with Foxconn and move to an alternative platform and get the same product with the same quality and the same assembly protocols without skipping a beat – I mean, anything is possible, but that to me sounds like a great tale of fiction,” said Stephen Roach, a professor at Yale University and former chairman of Morgan Stanley in Asia, the day before the Nikkei story broke.

China accounts for an important, but declining, share of Apple’s revenue: 10.22 per cent in the second quarter this year, according to Statista, down from 13.17 per cent in the previous quarter and its all-time peak of 17.96 in the first quarter of 2018.

“There is no question that if Apple goes, others will follow,” said Alex Capri, a visiting fellow at the National University of Singapore, who has been predicting decoupling for the past two years. “They are a primary link in the chain. There are a lot of links in that chain that are reliant on Apple. When you have something as big as Apple moving, others have to go where their customer needs them.”

Merle Hinrich, the founder of business media firm Global Sources and patron of the pro-trade Hinrich Foundation, suggested that Apple would be wise to diversify its supply chain and intimated that “decoupling” is a natural evolution in global trade.

“There are companies like Apple who have become overreliant on China. Is that pure supply-chain management on their part, or is it perhaps lack of foresight – they maybe did not foresee a time when it would become so politically charged?,” he said. “I think there are a lot of companies now that will reflect on their commitment to China and think it was a good decision when they made it, but it probably needs to be reviewed in conjunction with what we expect the geopolitical issues to be moving forward.”

However, that a move out of China is now being discussed at all points to the sudden decline in US-China relations, one which many feel is irreversible.

Indeed, it is China’s growing technological strength that many believe sparked decoupling. Five years ago, Roach wrote a book called Unbalanced: The Co-dependency of America and China, which said that the US and Chinese economies should not become codependent, since a fracture in the relationship would instigate decoupling. That fracture, he now said, came with China’s shift in economic policy, away from an industrial base and towards hi-tech innovation and consumption.

“The United States was far more comfortable with China staying in its old patterns of economic activity and views, to a large extent, this change as one that is more threatening and predictably, according to at least my theory, and has lashed out in response,” Roach said.

“My guess is that there is still a lot of hope that a lot of this is a bad dream and the tariffs will go away, and there will be some agreement on the structural issues that companies are complaining about. So I don't think we have completed a decoupling. We're in the early stages of a strong resistance to the relationship, catalysed by the very aggressive policy actions of the Trump administration.”

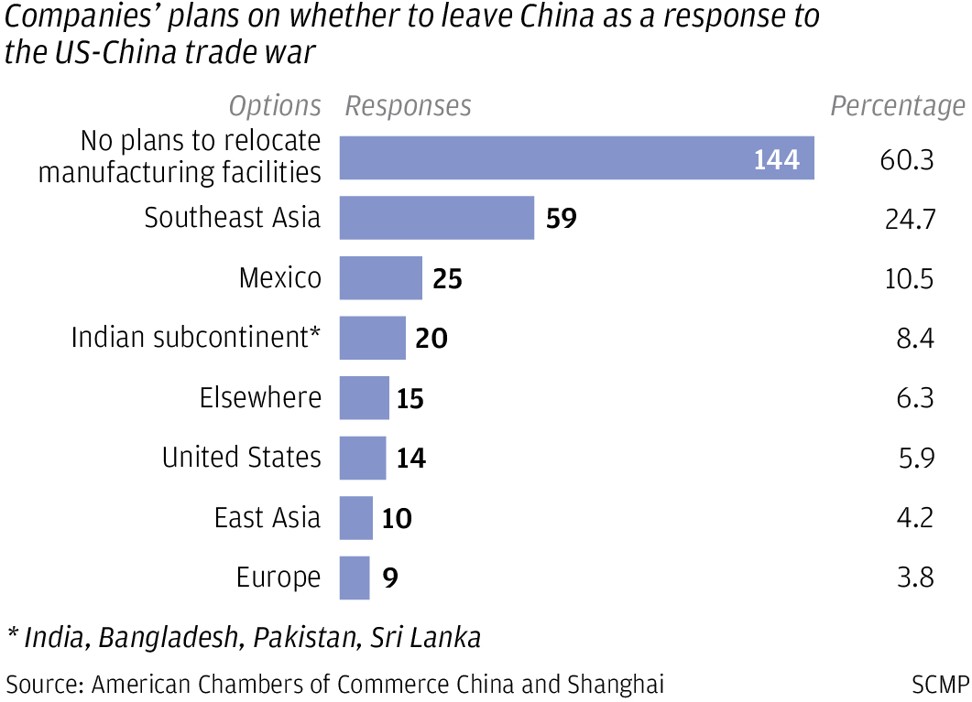

A US Chamber of Commerce in China survey published in May found that 60.4 per cent of companies had no plans to relocate their “China-based manufacturing facilities to other countries because of the tariffs and/or concerns over the future of US-China trade relations” – which suggested that many companies will not move unless they absolutely have to.

But there may be other factors at play, said Stewart Paterson, author of the 2018 book China, Trade and Power: Why the West's Economic Engagement Has Failed.

“There will be no big announcements. Corporations should not be out there saying ‘we're closing this factory and reopening in Bangladesh’. It is all very ‘hush-hush’,” he said.

The Chinese government, meanwhile, has been at pains to discourage further fragmentation of the US-China relationship.

At a summit in St Petersburg, Russia, at the start of June, Xi said: “I can hardly imagine a complete decoupling between China and the US. This is not the case that I would like to see, and I don’t think our American friends want to see it, and my friend Trump wouldn’t want to see it either.”

The following week, China’s foreign ministry spokesman Geng Shuang tried to further dampen thoughts of decoupling.

“Both countries have become each other's largest trading partner and important investment destinations,” said Geng. “The US has gained huge interests from China-US economic and trade cooperation.”

In the northern province of Shandong, however, the feeling of separation is becoming very real. Krassenstein’s suppliers have been in touch to ask if he needs better credit terms, whether there is an issue with price, desperately asking what they can do to keep his business. He stops short of using the word “decoupling”, saying that plenty of manufacturing will remain in China due to the quality of service and sheer size of the domestic market.

“But I've lived in China for the last 15 years and let’s just say more and more Americans are leaving China and setting up shop elsewhere. There is a feeling as an American living in China, it’s just not as warm and cosy as it used to be.”

Part two will ask whether the G20 summit will lack leadership and if important issues will go unresolved as the US-China stand-off continues.