As US-China trade talks resume, how much demand does Beijing have for American farm goods?

- US soybean exports have largely been replaced by those from Brazil, with the situation complicated by the impact of African swine fever

- US trade representative Robert Lighthizer is set to lead a US team to Shanghai next week to meet with Vice-Premier Liu He and Commerce Minister Zhong Shan

With negotiators from China and the United States set to have their first face-to-face talks since May next week, the likelihood of a large Chinese purchase of American agricultural goods appears to be growing.

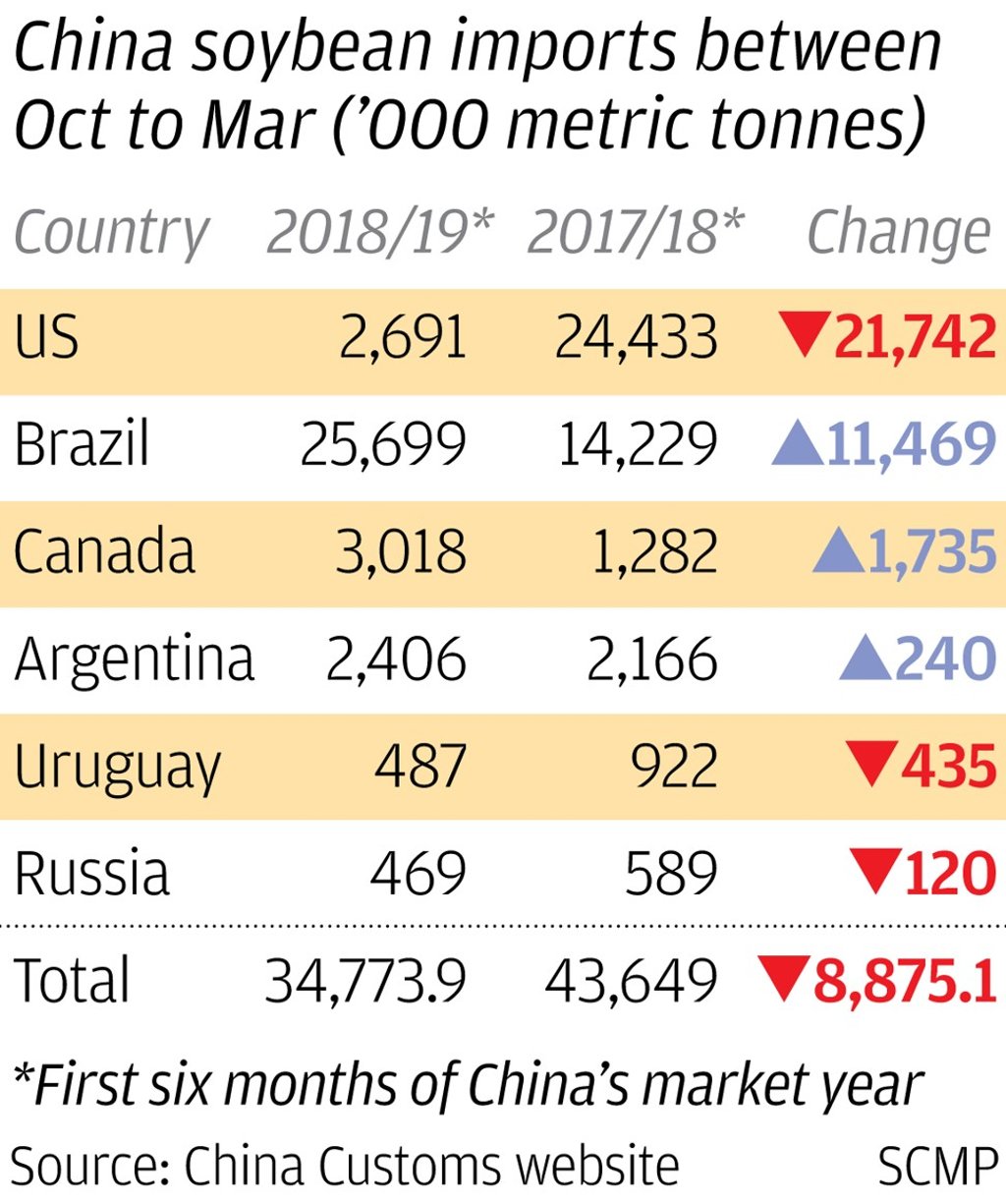

US Department of Agriculture (USDA) data from last week showed that China had made a 51,072 metric tonne purchase of sorghum, despite the grain being subject to a 25 per cent import tariff. This was the largest weekly purchase since April, but also came in the same week that China cancelled a 9,853 metric tonne purchase of soybeans. China’s imports of US soybeans have plummeted since the trade war began, but given the scale of its demand over recent years, soybeans are likely to be high on negotiators’ agenda.

Speaking to reporters in Washington on Tuesday, US Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue confirmed that agricultural purchases were underway.