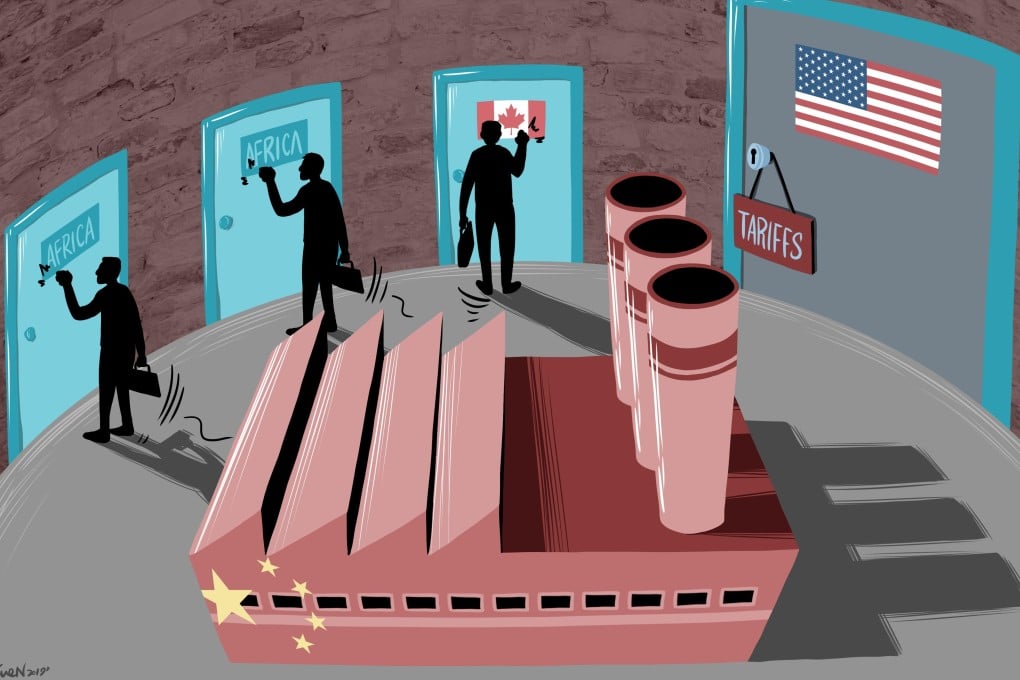

China’s Canton Fair highlights changing nature of nation’s manufacturing industry amid US trade war

- Tariff war launched by US President Donald Trump in June 2018 accelerated changes in China’s manufacturing and export industries that were already under way

- Some 200,000 potential buyers will still visit 60,767 exhibition booths in Guangzhou during the three week fair as China hangs onto its manufacturing role

When US President Donald Trump imposed tariffs on the first batch of imports from China in June 2018, a move which led to the start of the trade war between the world’s two largest economies, Chinese researchers put on a brave face, arguing that the levies would only have a marginal impact on exports and, therefore, on the overall economy.

That optimism was supported by facts. Among China’s total exports of US$2.3 trillion in 2017, shipments bound for the United States accounted for 19 per cent, suggesting that they played only a marginal role in supporting Chinese economic growth. Wei Jianguo, a former vice-minister at the Ministry of Commerce responsible for foreign trade, even suggested in late 2018 that Africa could replace the US to become China’s top export market by 2023.

But that observation does little to ease the increasing pain of the exhibitors of mostly low-end products at the Canton Fair, China’s oldest and largest export exhibition, which started last week in the southern city of Guangzhou.