China’s high-speed railway network advances full steam ahead, despite ‘grey rhino’ financial risk

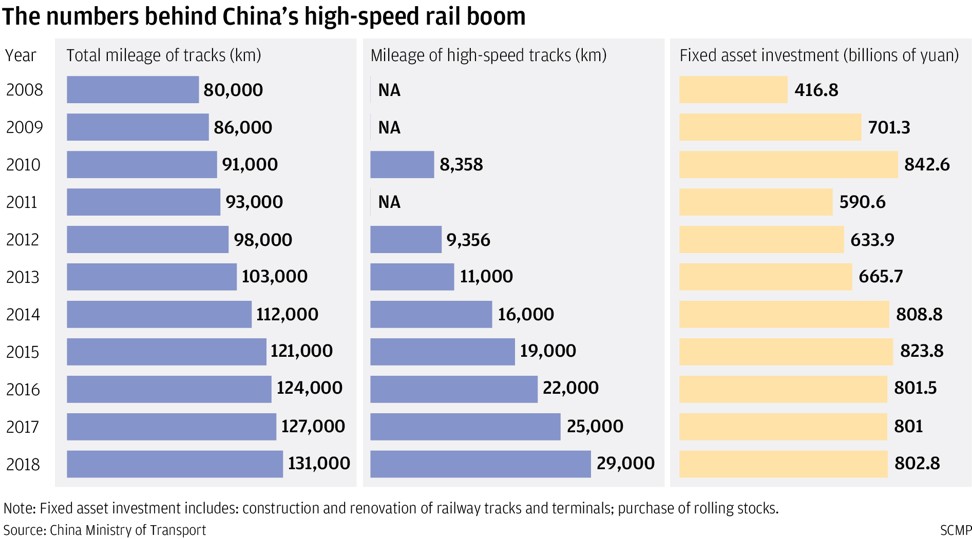

- China has expanded its high-speed railway system at a rapid pace over the past decade and at 35,000km it is now the world’s longest

- Despite being a source of national pride for many Chinese, there are lingering questions about its environmental footprint, safety record and financial viability

Despite it being just 200km from Beijing, Wang Dianqi rarely returned to his hometown of Zhangjiakou in the north of Hebei province before this winter.

It often took the academic editor up to five hours to drive the mountainous roads and congested motorways, and even longer if he took the old train system, which travelled along tracks built more than a century ago.

But on a recent morning as he boarded China’s first high-speed “smart” train, which boasts speeds of up to 350km an hour, fully automated driving and a home-grown Beidou navigation system, Wang said he had never felt so close.

“It is much more convenient,” said Wang, who was travelling with his wife to visit a sick relative. “The use of our own [Chinese] technologies also makes us very proud.”

The new service, launched ahead of the 2022 Winter Olympic Games, cuts travel time from China’s capital Beijing to Zhangjiakou, which will host some skiing events, by an hour and costs 90 yuan (US$13) for a one-way trip.

Despite initial fears that passenger numbers would be low, almost all seats were taken the weekend Wang was returning home, with many travellers on their way to go skiing, a popular new pastime among Beijing’s middle class.

The rail line started operation at the end of December and has so far proved a success. On average 85 per cent of seats were occupied during the first two weeks of operation, the official Xinhua News Agency reported.

The vast network, on which trains run at a minimum speed of 200km per hour, now connects all major cities across the country as well as numerous towns – cutting once horrendous journeys into a comfortable ride of a few hours.

For many, the railway system has become a source of national pride, including President Xi Jinping, whose slogan Fuxing or rejuvenation, has been used to name the next-generation bullet trains that are set to completely replace the Hexie series built under President Hu Jintao.

Xi has praised the new line from Beijing to Zhangjiakou, saying it was an example of China’s development and the “elevation of China’s national strength”.

The mountainous area on the outskirts of Beijing was once a nightmare for railway engineers. But in 1909, Yale-educated Jeme Tien Yow designed and oversaw construction of the original Beijing to Zhangjiakou line, becoming a national hero in the process.

More than a century on, China’s leaders are again trying to fuel patriotism with railway development and in the process prop up confidence in one-party rule.

Since the first high-speed railway line was inaugurated ahead of the 2008 Olympic Games, China has laid an extensive network of tracks. In the process it has changed the way Chinese people travel and improved connectivity throughout the country’s vast land mass.

But the expansion of the network has not been met with universal applause. There are lingering questions about its environmental footprint, safety record and financial viability.

Safety issues were exposed in 2011 after two bullet trains crashed in Wenzhou, a port city in Zhejiang province, killing 40 people and injuring hundreds. The incident sparked more frequent safety inspections and saw the maximum speed temporarily slowed to 300km per hour.

The project was tarnished further when former railways minister Liu Zhijun, who masterminded the high-speed railway line, received a suspended death sentence in 2013 for bribery and abuse of power in what was one of the biggest corruption cases to hit China.

The group’s 2019 transport revenue increased 6.1 per cent year on year to 818 billion yuan (US$119.2 billion), while all other revenue climbed 4.2 per cent to 362.3 billion yuan (US$52 billion).

“As a matter of fact, except the trunk lines connecting Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou, other lines can barely make it [in terms of profit],” said Zhao Jian, director of Beijing Jiaotong University’s urbanisation research centre.

Zhao has long insisted that China should prioritise construction of regular-speed rail, rather than high-speed links that are more costly, cater only to passengers and require night maintenance.

In an article published last year, the outspoken professor labelled China’s high-speed railway system a “grey rhino”, a term used by government officials to describe an obvious risk that is often neglected.

As debt has snowballed, Zhao said it was “just a matter of time” before the central government footed the bill, although it currently has a low explicit debt ratio.

However, debt poses a much higher threat to local governments in China, which have clocked up an estimated 18 trillion yuan (US$2 trillion) in credit, according to Zhao’s research.

“A lot of debt is buried in local government financing vehicles, which will not show up in statistics,” Zhao said, referring to the off-balance-sheet financing mechanism used by provincial and lower level governments to evade restrictions on borrowing.

So much of the network has been built not because of underlying demand, but as a way to promote growth and it has been financed by debt

Fraser Howie, a China observer and co-author of Red Capitalism: The Fragile Financial Foundations of China’s Extraordinary Rise, questioned if the lower journey times had really helped boost productivity and at what cost.

“So much of the network has been built not because of underlying demand, but as a way to promote growth and it has been financed by debt,” he said.

Even if China is able to absorb the overall losses, the subsidies provided for railway construction mean less funding available for other areas, Howie said.

“Do you want a faster train journey from Zhengzhou to Jilin City or a better school for your kid or health care for your mother?” he asked.

And there are few signs that the debt-fuelled investment frenzy will come to an immediate halt, either.

Some 800 billion yuan (US$116.6 billion) has been earmarked for railway investment in 2020, roughly in line with the previous three years, according to the transport ministry. Total investment in all of China’s railway network will top 4 trillion yuan (US$583 billion) between 2016 and 2020, higher than 3.5 trillion yuan outlined in the five-year development plan.

China’s top economic planning body, the National Development and Reform Commission, approved three high-speed rail projects, with a combined investment of 126.9 billion yuan (US$18.4 billion), in December alone.

Some have argued that the contribution the high-speed railway network makes in terms of consumption and the formation of city clusters – a new focus for China – is far bigger than is often accounted for.

The World Bank estimated in June last year the rate of return on China’s investment for the system in 2015 was 8 per cent, well above the opportunity cost of capital in China and most other countries for major long-term infrastructure investments.

“The impacts go well beyond the railway sector and include changed patterns of urban development, increases in tourism, and promotion of regional economic growth,” Martin Raiser, the organisation’s China country head, said in the evaluation.

There is also a noticeable impact on the national psyche.

Like many passengers, Wang and his wife were supportive of expanding the high-speed rail network, despite the debt associated with the projects.

“For such a populous country like ours, the high-speed network will allow people to travel more easily. It’s like [US President Franklin] Roosevelt’s New Deal. Once the network is formed, the rise will be natural,” Wang said.

“Every coin has two sides. We should take an optimistic attitude. Everything will get better.”