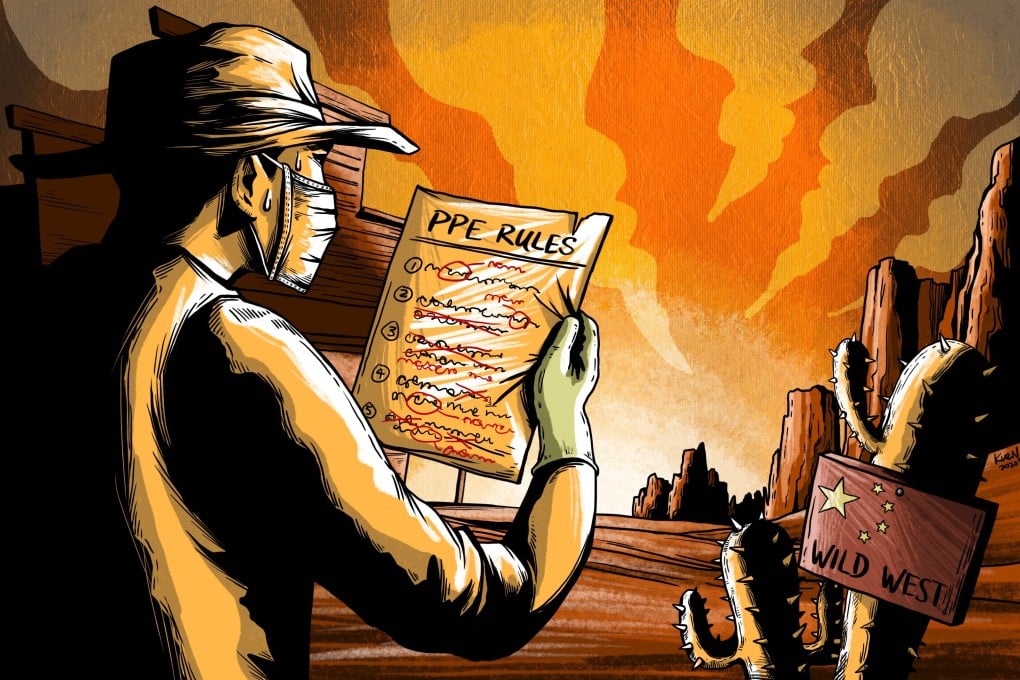

Coronavirus: inside China’s ‘Wild West’, where ‘mask machines are like cash printers’

- The coronavirus has led to an unprecedented seller’s market for masks and medical supplies in China, redrawing the rules of engagement

- An influx of new companies to the market has led to a dilution of quality and a host of bad actors, forcing China to change the rules

A “wild feeding frenzy” is under way in China for medical equipment crucial to containing the spread of the deadly coronavirus around the world.

Scalpers stake out factories with suitcases loaded with cash to secure millions of surgical masks hot off the production line. Dealers trade ventilators back and forth as if they were cargoes of coal, before they finally reach the end buyer carrying eye-watering mark-ups.

Governments wire eight-figure sums of money for vital equipment only to lose out to another government that was quicker to produce the cash.

We are slap bang in the middle of a gold rush for the year’s most sought-after commodities – masks, gloves, thermometers, ventilators, hospital beds, testing kits, hazmat suits, hand sanitiser and goggles – and according to those involved in the scramble, there are no holds barred.

The amount of money in the industry is amazing, it moves so fast. Due diligence is sometimes not an option

“This is the Wild West – the rules are being rewritten every day,” said Fabien Gaussorgues, co-founder of Sofeast, a quality control inspection company in Shenzhen.

“The amount of money in the industry is amazing, it moves so fast. Due diligence is sometimes not an option – people don’t have time. It is complicated on every side.”