Coronavirus: China set to push economic policy to new limits as National People’s Congress begins

- China is expected to reveal unprecedented fiscal support for its virus-hit economy at the National People’s Congress this week

- China’s fiscal deficit, GDP growth target still subject of heated debate on eve of annual gathering

This is the sixth in a nine-part series examining the issues that Chinese leaders face as they gather for their annual “two sessions” of the National People’s Congress and Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference this week. This instalment looks at the economic policies China will use to respond to fallout from the coronavirus pandemic.

China is set to unveil a series of extraordinary economic policies at its annual parliamentary gathering on Friday, including a fiscal package that could surpass that used during the global financial crisis a decade ago, as Beijing seeks to tackle threats from the coronavirus and an increasingly hostile world, analysts say.

While China has encountered economic shocks before, none has inflicted as much pain on companies, households and individuals as the Covid-19 pandemic.

In the first quarter, China was dragged into an economic contraction for the first time since 1976 and its role in global value chains is now under threat.

The international environment is turning from bad to worse … led by an increasingly confrontational US-China relationship. At home, it’s hard to say the economy has recovered

Tens of millions of Chinese migrant workers have been thrown out of work as sectors from catering to tourism struggle to get back on track. Export orders, meanwhile, are vanishing for many small businesses as the pandemic ravages the United States and Europe.

Following a three-month postponement, the National People’s Congress (NPC) will begin on Friday, where Beijing is expected to declare victory in bringing the pandemic under control.

The gathering will be the first major political assembly in China since the rapid spread of the outbreak began in late January, with nearly 3,000 legislative delegates and another 2,000 “political consultative committee members” set to gather in the Great Hall of People to hear the government’s work report read aloud by Premier Li Keqiang.

Chinese authorities are also expected to reveal how it will handle the most pressing issues facing the country.

03:35

The ‘two sessions’ explained: China’s most important political meetings of the year

Beijing has made it clear employment is the economic priority for China and it will loosen its purse strings to provide support to the economy. But the world has been kept guessing about what exactly will be done to aid struggling companies and households, while managing growing tensions with Washington.

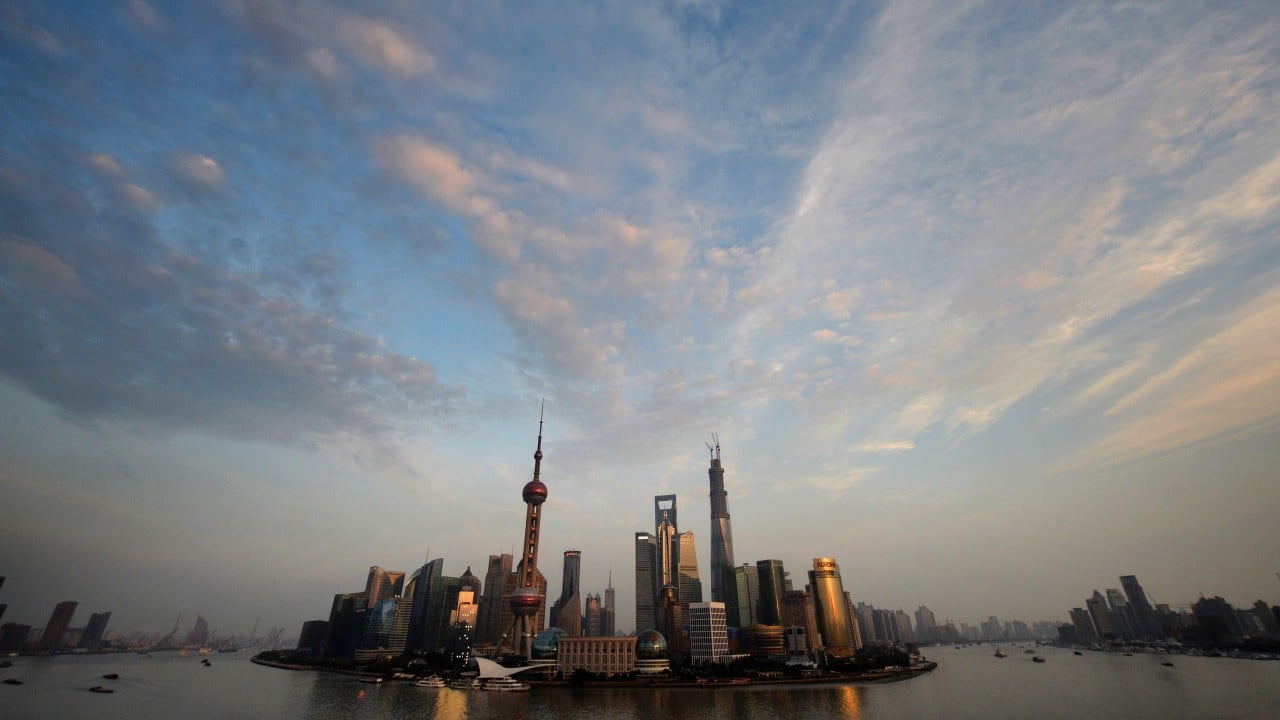

Li Weisen, an economics professor at the Fudan University in Shanghai, said China is facing mounting difficulties.

“The international environment is turning from bad to worse … led by an increasingly confrontational US-China relationship,” Li said. “At home, it’s hard to say the economy has recovered – it’s hard to find a happy restaurant owner in China these days as consumption and services are far from recovered.”

One long-standing limit that is expected to be smashed is China’s tradition of keeping the fiscal deficit ratio below 3 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP), long regarded as a red line to safeguard fiscal stability.

The coronavirus will punch a 3 trillion yuan (US$422.5 billion) hole in the federal budget in 2020, according to former finance minister Lou Jiwei.

To compensate, China would have to increase its on-budget fiscal deficit ratio to about 5.8 per cent of GDP from 2.8 per cent in 2019, as each percentage point of the ratio is equivalent to around 1 trillion yuan of fiscal deficit.

05:59

Coronavirus: What’s going to happen to China’s economy?

The proceeds from the special bonds will not be included in the central government budget, allowing Beijing to increase government spending without a massive increase in the fiscal deficit ratio. The size of the new bond issuance and how they will be issued is expected to be announced by Premier Li on Friday.

“There’s really no other option for China but to issue more bonds,” Fudan University’s Li said.

Former minister Lou predicted China’s central government would issue 2 trillion yuan worth of “special treasury bonds”, while local governments would offer an additional 3 trillion in bonds.

HSBC economists led by Qu Hongbin predicted that China’s on-budget fiscal deficit could be increased to 4 per cent of GDP in 2020.

There is a 50 per cent probability that Beijing will set its 2020 GDP growth target at 2-3 per cent, with a 50 per cent probability that Beijing will abandon a growth target for the whole year

But China’s broad deficit, which includes both on-budget deficit and off-budget debt, could be much higher, at around 11 per cent of GDP, said Ding Shuang, chief China economist at Standard Chartered bank.

Local government special purpose bonds could contribute up to 3.5 percentage points, or about 3.5 trillion yuan, with central government special bonds adding 1-2 percentage points, or up to 2 trillion yuan, he said.

The expectation that China will let its fiscal discipline slip is extraordinary, given that big deficits have been regarded as undesirable by leaders for decades.

Despite the historical aversion to breaching the limit, some analysts have called for China to be bolder and expand spending to save the economy.

“Many people oppose plans such as the 4 trillion yuan stimulus package in 2008 due to worries about excessive fiscal deficits and a quick rise in the government’s debt level,” Yu Yongding, a veteran Chinese economist with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, wrote earlier this month on Netease.com, a Chinese internet portal.

“They have a point but that doesn’t mean the Chinese government should rule out a fiscal policy for 2020 that is more expansive than a decade earlier.”

Aggressive fiscal spending was needed for China to achieve a growth rate of 3 per cent this year, he said.

01:56

Coronavirus: lockdown in northeast China strengthen amid fresh outbreak fears

“There is a 50 per cent probability that Beijing will set its 2020 GDP growth target at 2-3 per cent, with a 50 per cent probability that Beijing will abandon a growth target for the whole year,” Nomura economists led by Ting Lu said.

Beijing could also postpone its goal of doubling the size of the economy between 2010 and 2020 to next summer, as July 1 would mark the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party, Justin Lin Yifu, a former World Bank chief economist and current adviser to the Chinese government, said in an online speech over the weekend.

Regardless of the growth target, debate over how China should implement its stimulus efforts is still raging on the eve of the congress, reflecting deep divisions within Beijing.

05:26

Chinese businesses still face grim economic reality despite Covid-19 restrictions being lifted

Liu Shangxi, a researcher affiliated with the finance ministry, argued that the central bank could afford to buy 5 trillion yuan worth of special bonds, but his idea has been strongly opposed by other economists, including Ma Jun, an academic member in China’s monetary policy committee.

Ma argued that the “monetisation” of fiscal policy was dangerous because it could erode the nation’s fiscal discipline by creating the expectation of open-ended support from the central bank.

There are also heated discussions on how Beijing should allocate its stimulus package. For now, the government is relying on its old playbook of showering money on local governments and the state banking system, hoping increased spending on infrastructure and an ample supply of bank credit will trickle down to small businesses and households.

In a sharp contrast to the US, where the government is handing out cash directly to households, the Chinese government’s direct aid to small businesses and households has been limited.

The state-run unemployment welfare system, for instance, had given benefits to only 2.3 million people at the end of March, with most unemployed Chinese unable to access relief.

Zheng Bingwen, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and a member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Committee, has submitted a proposal to the government calling on the government to significantly expand unemployment benefit coverage.

Xu Hongcai, a non-resident senior fellow at the Centre for China and Globalisation, a think tank in Beijing, said it was time for China to provide direct subsidies to employers so that they can avoid laying off employees.

The Chinese government could subsidise 30 per cent of salaries for a given period to protect jobs, Xu said, similar to Hong Kong where the government is offering monthly support of up to HK$9,000 (US$1,200) per employee for a period of six months.

The ongoing debates partly reflect the inherent contradictions in Beijing’s economic policies. For instance, China’s increased spending on infrastructure, a necessary step to keep its economy afloat, is set to amplify the debt burdens and financial risks at local government level, ratings agency Moody’s warned in March.

Hu Xingdou, a Beijing-based independent economist, said the coronavirus has provided fresh incentive for China to give the state a bigger presence in the world’s second largest economy, which could be damaging in the long run.

“It seems there’s a growing view that a big government can solve all problems, and many are taking China’s state-led model as an advantage in the pandemic,” Hu said. “But if the government gets bigger and bigger … and it has to manage everything, it’s actually run against the trend toward market liberalisation.”

The next story in the series will examine the debate over the future path of China’s relations with the United States and how Beijing will respond to new international economic realities post-coronavirus pandemic. Until then, you can read the other five stories in the series: how Beijing is preparing for a post-Covid-19 world; how it is likely to ignore calls to investigate the coronavirus; the expectations for Beijing’s policy on Hong Kong; the expectations for China’s new military budget; the sharp decline of US-China ties, and where it may lead.