Explainer | Belt and Road Initiative debt: how big is it and what’s next?

- Chinese investments in developing countries have raised questions about whether such projects can ever generate enough money to pay off the debt

- Beijing will participate in the G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative, which offers relief for 77 developing nations’ debt repayments this year – on a case-by-case basis

What is the Belt and Road Initiative?

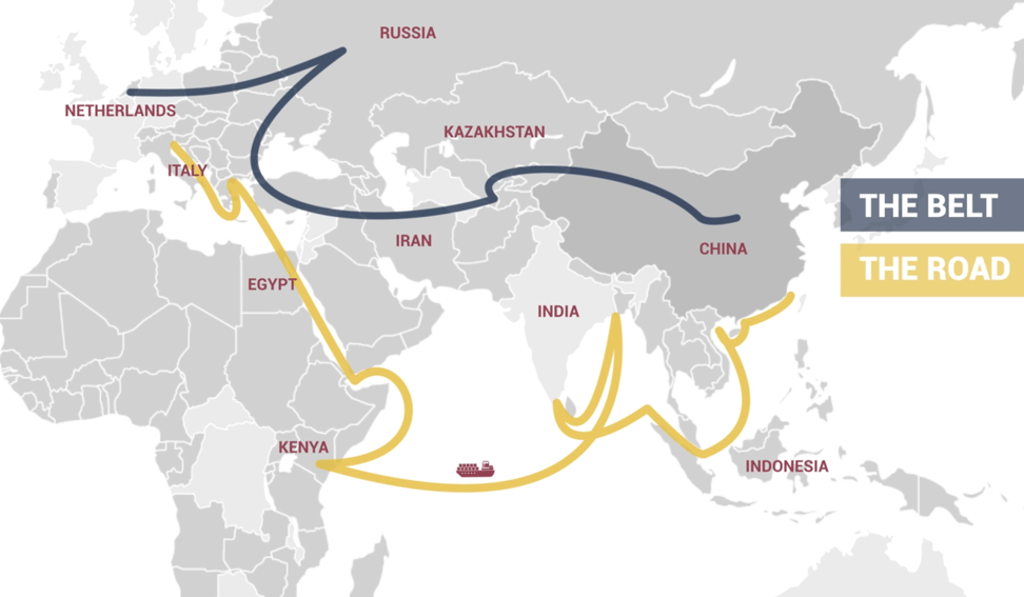

This ambitious plan involves connecting more than 70 countries on the continents of Asia, Europe and Africa via a series of rail, road and sea infrastructure projects, thus forming a “new Silk Road”. The goal for Beijing is to promote regional connections and economic integration, thereby expanding China’s economic and political influence.

How is the Belt and Road Initiative funded?

Mostly through bank loans, led by China’s three government policy banks, the large state-owned banks, and sovereign wealth funds such as the Silk Road Fund. These are the main sources of such lending, along with international financial institutions such as the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and New Development Bank.

However, while loans are offered to developing countries by global lenders, there are no specific attachments to projects labelled “belt and road”, meaning there are no official breakdowns of loans being identified as belt and road borrowing.

According to data provider Refinitiv, which runs a database that tracks belt and road projects, 59 per cent of the plan’s projects are owned by government entities as of September 2020. The private sector accounted for about 26 per cent. The remaining projects are defined as public-private ventures.