China to slash private lending rate cap from 24 per cent in effort to tackle ‘usurious loans’

- China’s Supreme Court and top economic planning agency say the interest rate ceiling protected by law will be slashed to crack down on ‘usurious loans’

- The new ruling could deal a heavy blow to China’s private lending market, analysts say, and may not have the desired result in reduced costs for small businesses

China’s courts currently protect an individual or business in a dispute that involves loans with an interest rate of under 24 per cent.

The nation’s top court did not specify what the new upper limit will be, but the ceiling could be four times that of the loan prime rate, according to the 21st Century Business Herald newspaper. China’s one-year loan prime rate is 3.85 per cent, meaning the upper limit could be as much as 15.4 per cent.

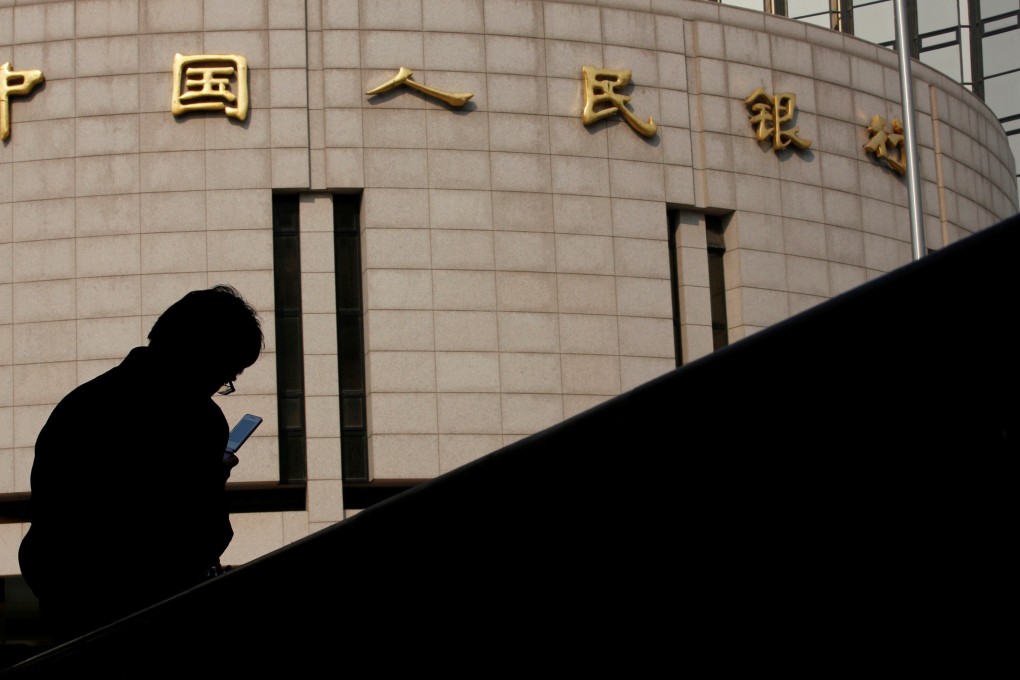

The amendment to the 2015 judicial order on private lending was announced by the Supreme People’s Court and China’s top economic planning agency earlier this week.

Lowering the cap is the most effective solution to relieve corporations from financing difficulty and high costs

As part of its effort to crack down on “usurious loans”, any interest rate above 36 per cent a year will be illegal, while the legality of annual interest rates between 24 and 36 per cent will be decided on a case-by-case basis.

“Many said that the current private lending rate is too high. We are now running against the clock to study the issue,” said Zheng Xuelin, chief judge of the Supreme Court’s first civil division.