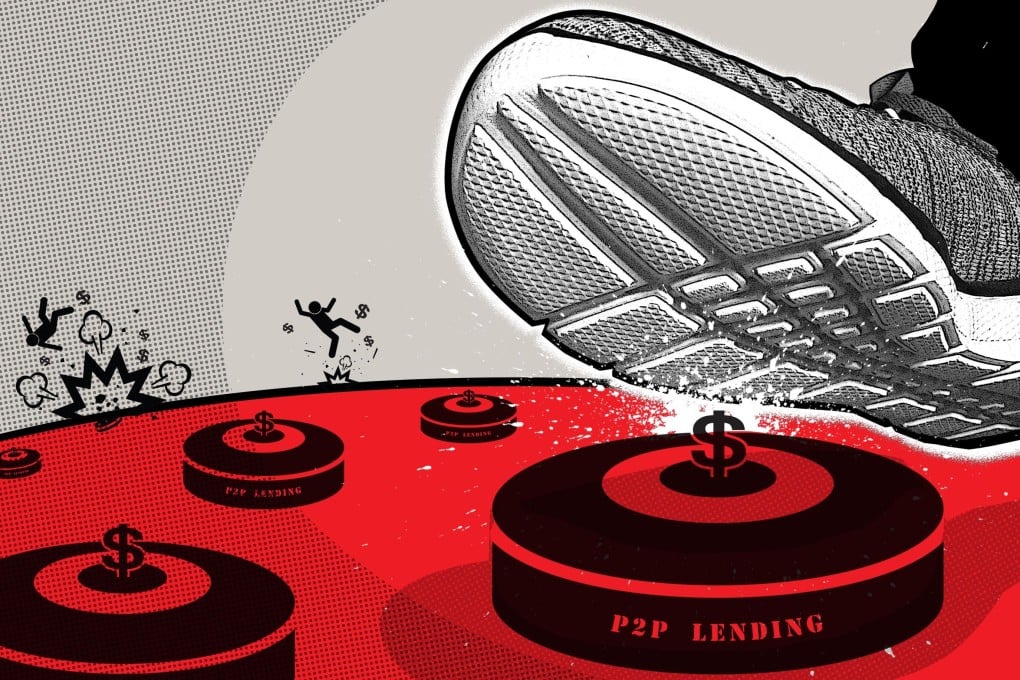

China’s P2P purge leaves millions of victims out in the cold, with losses in the billions, as concerns of social unrest swirl

- The shroud over peer-to-peer lending firms has fallen, and China’s banking regulator says all such platforms across the country have ceased operations – but many life savings are feared lost

- Just a few years ago, P2P lending platforms were touted as a model to reshape China’s financial landscape, but a lack of regulations saw fly-by-night operators run amok

Karen Kong has not got a restful night’s sleep in the past half a year, after learning that her mother invested all of the family’s savings – more than 1 million yuan (US$153,000) – in a little known peer-to-peer (P2P) lending platform.

Worries soon turned into anger and despair as the Beijing-based Jieyue United made its way onto the Chinese government’s liquidation list, and the chance of getting their money back appears to be dwindling.

“No one can give us a clear timetable for the settlement, or even a reply,” she said, pointing to a stack of petition papers signed by investors, appeal letters and photocopied evidence – all of which were rejected by local government agencies in Beijing.

“A lot of the investments are life savings and the pensions of senior citizens. How can they make a living,” asked Kong, who lives in the eastern province of Shandong. “They must give us an explanation and a solution.”

The shroud over P2P firms has fallen, with China’s banking regulator announcing last month that it had shut down all such platforms. However, the financial time bomb is far from being defused for millions of families who invested billions of yuan, and a very real concern exists that mishandling the situation could lead to social unrest.