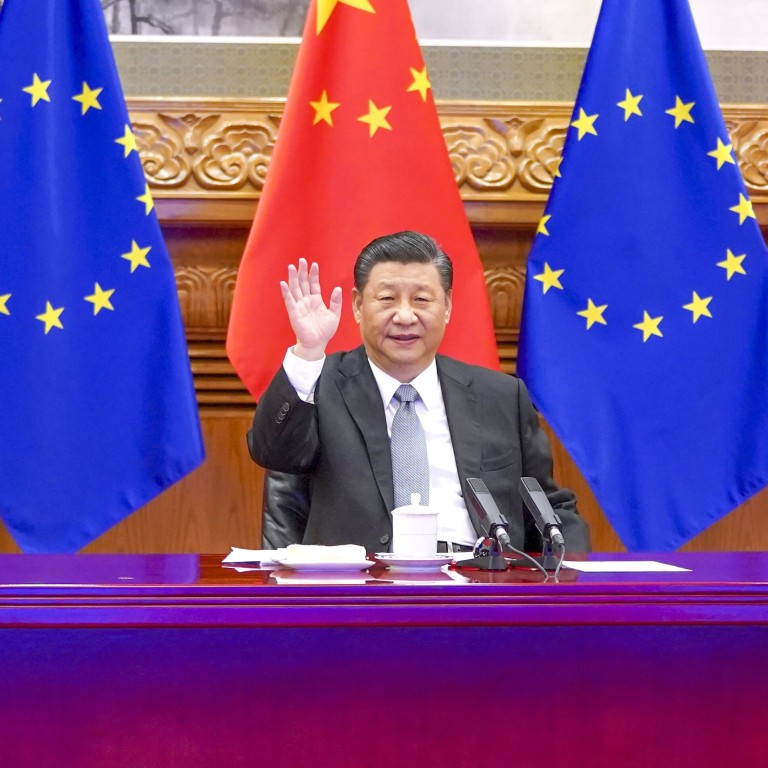

EU-China investment treaty: top European negotiator Maria Martin-Prat defends forced-labour provisions amid criticism

- Maria Martin-Prat, who led the European Union’s negotiations with China, said the EU is looking into autonomous measures to bolster forced-labour screenings

- A European Commission representative also shoots down rumours that Huawei provisions were added to China deal after signing

The chief negotiator of the European Union’s new investment deal with China has defended the forced-labour provisions, saying that Beijing’s obligations to ratify key international standards “can be measured over time”.

Speaking at a webinar on Wednesday, Maria Martin-Prat said Brussels would continue to push “autonomous measures on forced labour”, implying that it would be unreasonable to expect an investment treaty to be a silver bullet for such social issues.

“Even though we think it’s very important to engage, for instance, in the ratification of the ILO (International Labour Organization) conventions, and to work with other countries to make sure that practices such as forced labour are eradicated, we don’t believe the EU can achieve that goal on that basis only … what partners may be willing to commit themselves to do under a treaty. And we are looking into, as well, autonomous measures to fight against forced labour,” she said.

The named conventions are related to forced labour and were among the final chapters of the deal to be agreed, according to an early draft of the text seen by the South China Morning Post.

A European Commission representative on the webinar, who asked not to be named, said that “China must take steps, and it will be increasingly difficult as time passes to justify that you’re working towards a ratification process”, should Beijing not be moving in the right direction.

They pointed to a ruling this week on the EU-South Korea free-trade agreement which found that Seoul had not made sufficient efforts towards ratifying core principals of the ILO as part a free-trade agreement with the EU reached in 2009. Despite this, the panel found that Korea had not “breached” the terms of the deal.

“I think you can, for instance, see that the commitments are practically identical to those that were taken by Korea in its free-trade agreement,” the representative said.

But critics have said that this could be indicative of how such provisions might work under the CAI.

“The language in the CAI is even weaker; I don’t see how the EU can aggressively enforce this,” said Henry Gao, a professor of trade law at Singapore Management University.

More analysts have suggested that the Korean case shows how difficult China’s labour commitments will be to enforce, since they are not applicable to the state-to-state dispute-settlement cause of the CAI.

Steven Peers, a professor specialising in EU and trade law at the University of Essex, said the Korean ruling “sends a converse message to non-EU countries: that a delay of nearly a decade in ratifying such conventions, including extra tardiness in ratifying one important convention, is acceptable”.

“In particular, we now know that this is the message that the EU would be sending to China via the EU-China investment treaty as regards China ratifying ILO forced-labour conventions. Whether this is sufficient will likely be subject to much debate in the near future,” Peers said in a blog post.

“I hear that in the so-called ‘legal scrubbing’ phase of work on CAI the Chinese side is trying to reintroduce their request that member states which limit Huawei access to 5G networks should not benefit from market opening in China,” tweeted Reinhard Butikofer, chair of the European Parliament Delegation for Relations with China.

The unnamed official said that such claims “really don’t respond to reality”.

“Legal scrubbing is legal scrubbing, the negotiations are closed. They were closed in principal at the end of the year. I don’t see how and why people argue that there will be reopening to include anything related to telecommunications or related to Huawei.”

At the webinar, hosted by the Institute for International Trade at the University of Adelaide in Australia, Bryan Mercurio, a trade law professor at Chinese University of Hong Kong, said the EU should avoid overselling what it perceives to be the deal’s human rights chops.

“This is a services-and-investment agreement,” Mercurio said. “We cannot expect it to be a comprehensive labour or environment agreement. If that’s what we wanted, negotiate a labour or environment agreement. Don’t expect trade and investment to solve every problem in the world.”