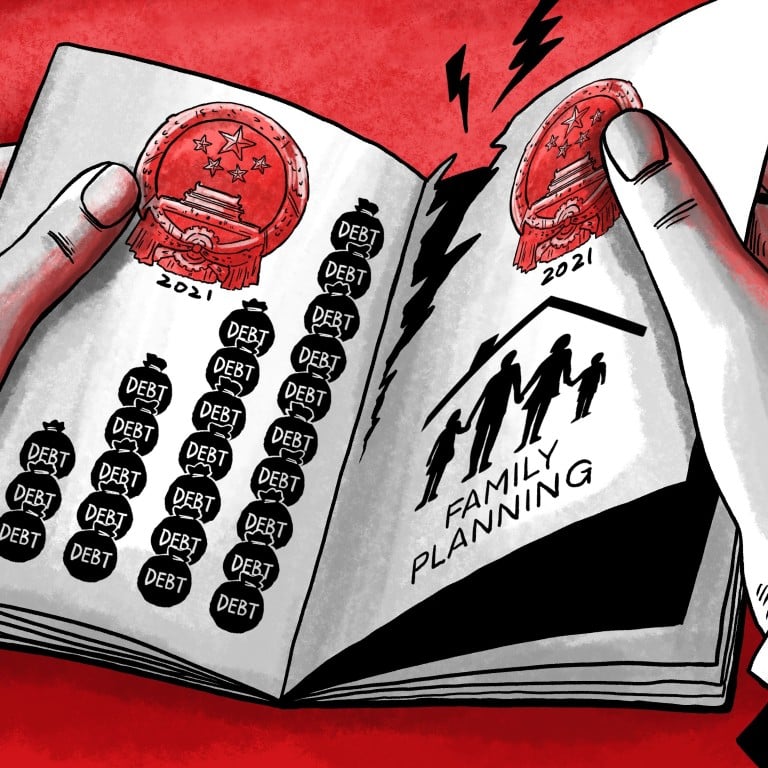

China’s ‘two sessions’: population decline, rising debt worries to be hot topics for political elite

- China’s population could be surpassed by India’s as early as 2027 due to a declining birth rate, even after its one-child policy was abandoned in 2016

- Beijing is also increasingly concerned about its level of debt, which has risen rapidly over the past 12 months as it fought the impact of the coronavirus

China’s political elite will face a number of challenges when they gather in Beijing next week for the year’s biggest legislative set piece – the meetings of the National People’s Congress and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, informally known as the “two sessions”. In this latest part of a series looking at the key items on the agenda, we examine two of the major problems facing China – a declining population and a rising level of debt.

Just over five years ago, when China ended its controversial, decades-old one-child policy, concerns over a demographic crisis seemed far-fetched.

Fast forward to 2021, and those concerns and a rising level of debt have become two of the biggest issues hanging over the world’s most populous nation, which is also the second-largest economy behind the United States.

China’s low birth rate

Even though the complete 2020 new births and population data has not yet been released, China’s central government has already raised the possibility that its population could be surpassed by India as early as 2027, citing a low fertility rate.

China’s fertility rate in 2019 fell to 1.47 births per woman during their childbearing years, just ahead of Japan which has long suffered from a low birth rate and a declining population.

I think that the words ‘family planning’ will not appear in this year’s government work report just like in recent years. No mention of it means that the birth control policy is being phased out

Birth data from some provinces and cities has already provided an early indicator of the problem, with the declines ranging from 10 to 30 per cent.

03:42

SCMP Explains: The ‘two sessions’ – China’s most important political meetings of the year

The figure is not China’s official birth rate for 2020 as the hukou system does not include the entire population, but is another red flag.

Over the past five years, a number of Chinese legislators and demographers have repeatedly proposed completely abandoning the government’s birth control policy, which is still in China’s constitution, with the impact following the change to a two-child policy in 2016 fading.

The words “family planning” have also not been mentioned in the government work report, released during the annual “two sessions”, since the one-child policy was abandoned.

“I think that the words ‘family planning’ will not appear in this year’s government work report just like in recent years. No mention of it means that the birth control policy is being phased out,” said He Yafu, a Chinese demographer.

“It is unlikely that the two sessions this year will explicitly be abolishing the family planning policy, because last year’s fifth plenary session only vaguely mentioned ‘enhancing the inclusiveness of the birth policy’.”

The main goal of last year’s plenary session, one of the most important political meetings of China’s Communist Party leadership, was discussing the five-year plan covering 2021-25.

An “inclusive” birth policy has been read as a signal of further reductions in birth restrictions, and experts estimate that the official abolition of “family planning” may kick off during the sixth plenary session later this year.

“I estimated a while back that population policy adjustments would not take place at the two sessions, but rather at the sixth plenary session at the end of the year, after the results of the census are released,” said Yi Fuxian, senior scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

In recent years, many delegates from the National People’s Congress (NPC) and Chinese People‘s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), the two simultaneous meetings that make up the two sessions, have submitted motions and proposals related to population policies.

Is China concerned about its population?

He also called for more central government investment in childcare and preschool education to create incentives for couples to have more babies.

In a reply from August that was only released in February, the National Health Commission said the northeastern provinces of Heilongjiang, Liaoning and Jilin, which have the lowest fertility rates and the highest economic burden for elder care of all the 31 provincial-level jurisdictions in the country, can experiment with lifting restrictions after more research is conducted to gauge the impact on the economy.

This year, the Chinese Peasants’ and Workers’ Democratic Party, one of the eight minority parties in China, plans to submit a proposal on boosting the birth rate, according to the 21st Century Business Herald. The party is led by Chen Zhu, who oversaw family planning as minister of health between 2007-13.

Some of the suggestions include extending maternity leave from three to six months, guaranteeing paternity leave for fathers, making childcare costs tax deductible, subsidising education costs for second children, giving policy support for those seeking to buy bigger houses for growing families as well as subsidies and tax breaks for employers that retain jobs for pregnant mothers.

China’s debt problems

Another priority this year for Chinese policymakers is reducing overall public debt as Beijing is increasingly concerned about the level of leverage, which has risen rapidly over the past 12 months.

China is expected to announce its fiscal deficit target and local government debt quota for 2021 on Friday. Last year, the government debt to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio shot to 270.1 per cent from 246.5 per cent in 2019 after Beijing raised its budget deficit target and increased local government bond issuance in a bid to boost the economy and save jobs in industries hit by the coronavirus pandemic.

Beijing has been increasingly uneasy with the sustainability of public debt levels amid deteriorating local government revenues and growing pressure on refinancing existing debt.

If we continue to issue bonds on the same scale as [2020] we may enter a risk alarm zone [in 2021]

China’s local government debt stood at 26.02 trillion yuan (US$4 trillion) at the end of January, according to the Ministry of Finance.

“If we continue to issue bonds on the same scale as [2020] we may enter a risk alarm zone [in 2021]. From the perspective of the sources of funds for the repayment of special purpose bonds, there are currently outstanding problems such as insufficient source of funding and single financing sources for debt repayment,” Xue Xiaogan, deputy director of the Ministry of Finance’s Government Debt Research and Evaluation Centre, said in December.

“In this context, it is very important to make a reasonable determination of the scale of borrowing, determine the source of debt repayment, and strictly prevent and control debt risks.”

China debt: how big is it and who owns it?

And total government bond issuance will be cut to 6.85 trillion yuan in 2021 from 8.5 trillion yuan last year, Hu predicts.

“In 2021, the broad fiscal deficit is set to return to normal. For policymakers, the goal should be to stabilise the government debt-to-GDP ratio, which grew 7 percentage points in 2020,” Hu said.

Last year, Beijing increased the special bond issuance, both at the central and local levels, to a total of 3.75 trillion from 3.5 trillion yuan a year earlier.

However, infrastructure fixed asset investment in 2020 only grew by 3.4 per cent compared to 3.3 per cent in 2019, a sign that the extra debt load did not wholly compensate for the overall fall in fixed asset investment.

China’s local government new bond issuance is likely to be 6.8 trillion yuan this year, made up of 3.3 trillion yuan for general purpose bonds and 3.5 trillion yuan for special purpose bonds, according to Zhongtai Securities.

As the economy continues to recover, the demand for stimulating the economy by increasing infrastructure investment declines

China is also unlikely to again issue 1 trillion yuan in special treasury bonds to boost government spending as it did last year, it added.

“As the economy continues to recover, the demand for stimulating the economy by increasing infrastructure investment declines,” said analysts from Industrial Securities.

“It is evident that the local debt limit in 2021 will not be front loaded. The balance of local government debt is subject to quota management and considerations of debt risk prevention. It is more likely that the quota on special purpose issuance will be lowered.”