China GDP: Beijing sets moderate 2021 economic growth target as focus shifts to debt reduction

- Premier Li Keqiang announced a gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate target of ‘above 6 per cent’ for this year during Friday’s National People’s Congregss

- Most analysts project China’s economy will grow by more than 8 per cent this year as it recovers from the impact of the coronavirus

China’s decision to revive its decades-long tradition of setting an economic growth target for 2021 is seen as a vote of confidence in its continued recovery from the effects of the coronavirus, but the low bar suggests focus has started to pivot back towards deleveraging to reduce debt and financial risks.

“A target of over 6 per cent will enable all of us to devote full energy to promoting reform, innovation, and high-quality development,” Li told the country’s legislature as he delivered the annual government work report.

2021 offers the best opportunity since 2008 [after the global financial crisis], in the sense that the government has absolutely no pressure to maintain growth

In addition, the low target gives the government more leeway to address some chronic problems, in particular the risks of financial bubbles and rising debt, analysts said.

“2021 offers the best opportunity since 2008 [after the global financial crisis], in the sense that the government has absolutely no pressure to maintain growth,” said Zhang Zhiwei, chief economist at Pinpoint Asset Management.

“We must not only consider the situation of this year, but also take into account the development needs for next year and the year after next as a whole, to avoid the projected target of violent fluctuations in different years,” he said.

China’s economic growth target has not only a symbolic meaning, but also should be seen as a clear beacon for how policy will be formed and implemented in the year ahead, analysts said.

“[The target of above 6 per cent] means a series of policy adjustments, especially in monetary policy and financial supervision,” Guan Qingyou, the chief economist at the Reality Institute of Advanced Finance, a private think tank, wrote on Friday on Weibo, China’s Twitter-like platform.

The target of 11 million is not a low one, it is an arduous task to achieve this goal

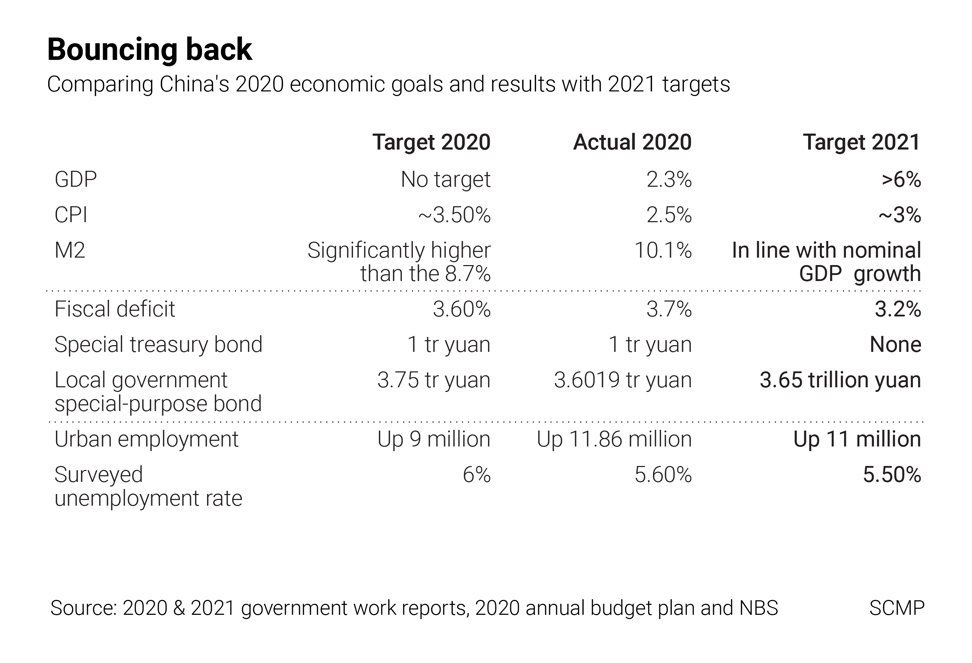

China also set a target of creating over 11 million new urban jobs this year, the same target as in 2019 before the coronavirus outbreak, and a surveyed urban unemployment rate of 5.5 per cent, compared to around 6 per cent last year.

These targets are important for overall social stability, which Beijing equates with high levels of employment among its citizens.

“The Chinese economy is still in the process of recovery and development, market conditions are complex and severe, and various uncertain factors are still increasing.”

In a sign of the shift from economic stimulus to a stronger willingness to reduce debt, China trimmed back the central government’s fiscal deficit-to-GDP ratio target to 3.2 per cent from 3.6 per cent in 2020.

“These targets have two implications: First, it reinforces the contention that Beijing really has no intention to make a sharp policy shift,” said Nomura chief economist Lu Ting.

“The pace of policy normalisation should be quite moderate. Second, there are negative implications from the increasing dependence of China’s local governments on debt financing. Once they borrow a lot [as they did last year], it is difficult to borrow less.”

The overarching target for China’s policymakers this year is to stabilise the [debt-to -GDP] ratio. As such, policy tapering could happen in various areas such as monetary, fiscal and property

The lower fiscal targets mean that China’s fiscal spending will decelerate, driving down infrastructure investment growth to 2 per cent this year from 3.4 per cent last year as China focuses on stabilising its overall leverage, according to Larry Hu, head of Greater China economics at Macquarie Group.

“The overarching target for China’s policymakers this year is to stabilise the [debt-to -GDP] ratio. As such, policy tapering could happen in various areas such as monetary, fiscal and property,” said Hu.

China’s debt-to-GDP ratio rose to 270.1 per cent last year from 246.5 per cent in 2019, according to figures from National Institution for Finance & Development.

Last year, Beijing raised its budget deficit target and increased local government bond issuance in a bid to boost the economy and save jobs in industries hit by the coronavirus, contributing to the sharp rise of overall leverage.

China’s powerful planning agency, the National Development and Reform Commission, also underscored the government‘s renewed emphasis on reducing financial risks on Friday by saying it would “strictly implement the risk prevention and control of local government debt” and “resolutely curb the rise of hidden debts”.

“The modest reduction in the forecast budget deficit and special bond quota [highlights] the challenge that policymakers face in controlling financial risks as the economy recovers,” said Martin Petch, senior credit officer at the Sovereign Risk Group, part of Moody’s Investors Service.