How a sweeping US infrastructure plan might spur financial havoc in China

- Economists debate whether proposed US$2 trillion infrastructure programme would cause inflation at home that could be exported

- ‘I would be surprised if the Fed wasn’t compelled to raise rates by sometime next year,’ one analyst says.

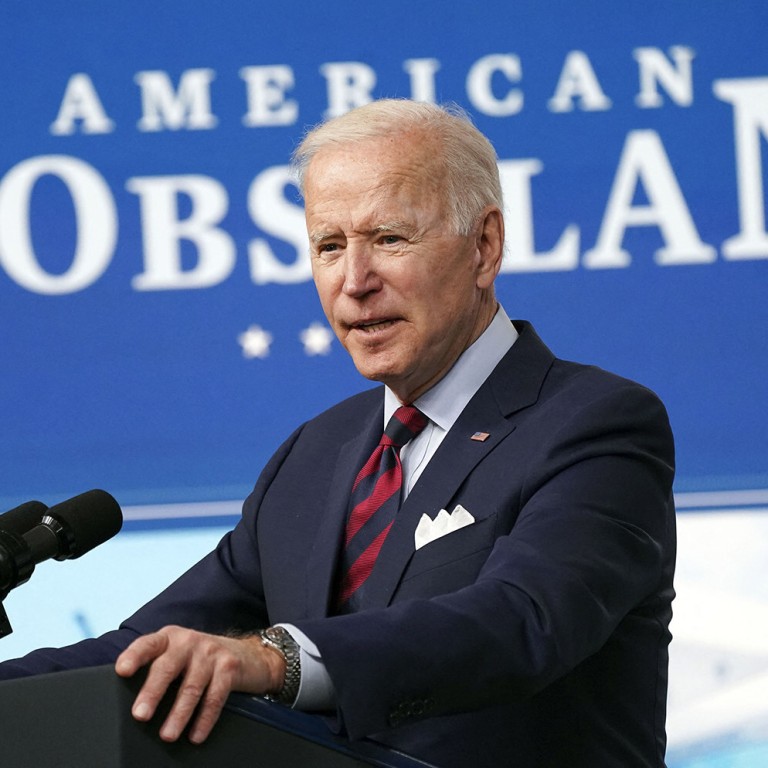

As the Biden administration pushes its proposed US$2 trillion domestic infrastructure programme forward, it is sparking debate about the programme’s potential to wreak havoc in emerging markets.

If passed, the total amount of extra capital pumped into the US economy in relief and recovery packages since March 2020 – at the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic – would swell to US$7.2 trillion, the largest such capital infusion since World War II.

Policy watchers agree that the new plan would help upgrade ageing bridges and roads for the 21st century, as well as fight climate change. But they can’t agree on whether excess liquidity would cause large amounts of capital to rush in and out of emerging markets like those of China, Brazil, and Mexico, distorting them.

The issue comes down to whether the proposed infrastructure programme – the American Jobs Plan – will trigger inflation and price increases in the US, which might then cause capital flows in other countries to fluctuate sharply.

Last month, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell said the Fed did not expect to raise interest rates until 2023. But since then, inflation indicators have ticked up.

Consumer prices, a key gauge for inflation, rose 2.6 per cent in March from the year earlier, the highest uptick since August 2018, the Labour Department reported last week.

Also last week, the Commerce Department reported that early indication of US retail sales jumped 9.8 per cent for March, exceeding estimates as recovery checks sent to households started to seep into the economy.

With loose policies, the central bank looks to rejuvenate the worst-performing US economy since 1946 – battered by the pandemic that has claimed more than 560,000 American lives – which contracted 3.5 per cent in 2020.

China moves to counter ‘turmoil in financial markets’

In promoting the infrastructure bill, Biden said that to grow the economy, “inaction isn’t an option”, and called the legislation “a once-in-a-generation investment in America”.

The proposed programmes – which include everything from revitalising manufacturing to investing in research in tech to providing high-speed broadband to all Americans – would boost the economy, reduce carbon emissions and narrow economic inequality, his advisers contend.

One camp of more traditional economists stressed the correlation between easy-money policies and inflation, as seen in the 1970s. With that kind of cash sloshing around, they say, inflation is bound to pick up.

“The Fed will try to hold out raising rates as long as possible, and what I mean by that is until inflation expectations start going out about 3 per cent,” said Benn Steil, director of international economics at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York.

“But I would be surprised if the Fed wasn’t compelled to raise rates by sometime next year.”

If that happens, it could draw foreign capital into the US as yields on bonds and loans rise – and away from emerging markets, leading to sharp outflows there.

Steil called the infrastructure bill “too large”, and said that it “puts enormous pressure on emerging-market central banks to raise rates in order to avoid massive capital outflows”.

Andrew Bishop, global head of policy research at Signum Global Advisors in Washington, said that “the US’s level of activity is likely to be so high in coming months that it may force the Fed to taper sooner than many had originally expected”.

One prominent critic of the bill is Lawrence Summers, the high-profile Democratic economist who was director of the national economic council in the Obama White House.

Summers, who was also Treasury Secretary in the Clinton administration from 1999 to 2001, wrote in a column for The Washington Post that “there is a chance that macroeconomic stimulus on a scale closer to World War II levels than normal recession levels will set off inflationary pressures of a kind we have not seen in a generation”.

The bill is likely to face a tough time in Congress. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said this month she wanted to get the legislation passed by both chambers before the August recess.

For the Senate to approve it by conventional means, though, at least 10 Republicans would need to support it, which seems a tall order. Republicans did not vote for Biden’s earlier Covid-19 relief bill, and take issue with the size of this proposal.

Without that support, Democrats, who hold the slimmest of majorities in the Senate, could push the legislation through using a process known as reconciliation, which lets budget-related bills pass on a simple majority vote.

American Rescue Plan: US stimulus seen widening trade deficit with China

Pelosi said she’d prefer the package to pass on a bipartisan basis. And President Biden has said he wants Republican input. But he has also signalled he will move forward without it if consensus appears impossible.

Under the plan, US$2 trillion would be spent across eight years on an expansive list of infrastructure projects.

China has identified the proposals as a threat to trigger “imported inflation”, the nation’s former finance minister Lou Jiwei said last month. Should US interest rates rise as a result of the infusion of trillions of dollars, other countries would be forced to raise rates to mirror those of the US.

China has tight controls on its capital flows, restricting the amount leaving the country to US$50,000 per person each year. But Steil said that would not be enough to limit outflows.

“Capital restrictions are leaky and they are not sufficient to immunise the PBOC – China’s central bank – against the necessity of raising rates,” he said.

Should the Fed keep the rates steady in the face of inflation, that would lead to capital swinging the other direction, exiting the US and flooding into higher-yielding emerging markets.

Biden discusses US$2 trillion jobs and infrastructure proposal

That possibility concerns China, which already spent 2020 dealing with huge capital inflows. Foreign holdings of Chinese stocks jumped 62 per cent from a year earlier to 3.4 trillion yuan (US$520 billion), and the bond market saw a 47 per cent rise, to 3.3 trillion yuan.

While inflows have eased this year, Beijing said last month it was worried that the infrastructure package, along with the Fed’s decision to keep interest rates low, would pump cash into an American economy already flush with liquidity.

Central bankers in the emerging markets of Brazil, Russia and Turkey raised rates last month based, they said, on inflation concerns.

Another group of more Keynesian economists contends that inflation is not a major worry.

“We think the likeliest outlook over the next several months is for inflation to rise modestly” and “to fade back to a lower pace”, Jared Bernstein, a senior fellow at the Centre on Budget and Policy Priorities think tank wrote in a post on the White House website.

“Such a transitory rise in inflation would be consistent with some prior episodes in American history coming out of a pandemic or when the labour market has quickly shifted, such as demobilisation from wars,” said Bernstein, an economic adviser to Biden when he was vice-president in the Obama administration.

In his remarks at the International Monetary Fund Spring Meetings, Powell, the Fed chairman, also described any inflation that might occur as transitory.

Biden’s jobs plan shows great economies think alike in a crisis

“Whatever costs people have to bear in prices because supplies are temporarily tight as the economy reopens, those won’t be repeated next year. We think that this supply change will adapt and become more efficient,” he said.

Last week, Powell reiterated that the Fed was unlikely to raise interest rates this year, affirming the central bank’s commitment to keep loose monetary policy in place.

Others contend that monetary policy and inflation no longer held the linear relationship like they used to.

“We are in a different world, an uncharted territory,” said Lourdes Casanova, director of the Emerging Markets Institute at Cornell University.

“Part of the reason inflation has stayed low was because as global value chains are more efficient; that keeps products cheaper.”

But Casanova acknowledged that if the US dollar remains relatively strong, the infusion of funds from the infrastructure programme might trigger debt defaults in countries like Argentina, Brazil, Angola, and Zambia, which all carry high dollar-denominated debt and have weak currencies.

China warns ‘side effects’ of US stimulus risk sharp market correction

“On the whole, US stimulus is a net positive because a rising US economy lifts all boats,” she said. “If the US does well it will help the rest of the world.”

Steil, the CFR economist, conceded that “in the short term, the stimulus is positive for emerging markets. You can expect that the US will be importing more, you can expect some of this new liquidity that’s being created to leak abroad, so that it’ll increase the demand for foreign financial assets. But it really depends on whose thesis is correct.

“My expectation is that inflation will rise more quickly than the Fed is forecasting. If I am right, emerging markets can expect tougher times ahead.”