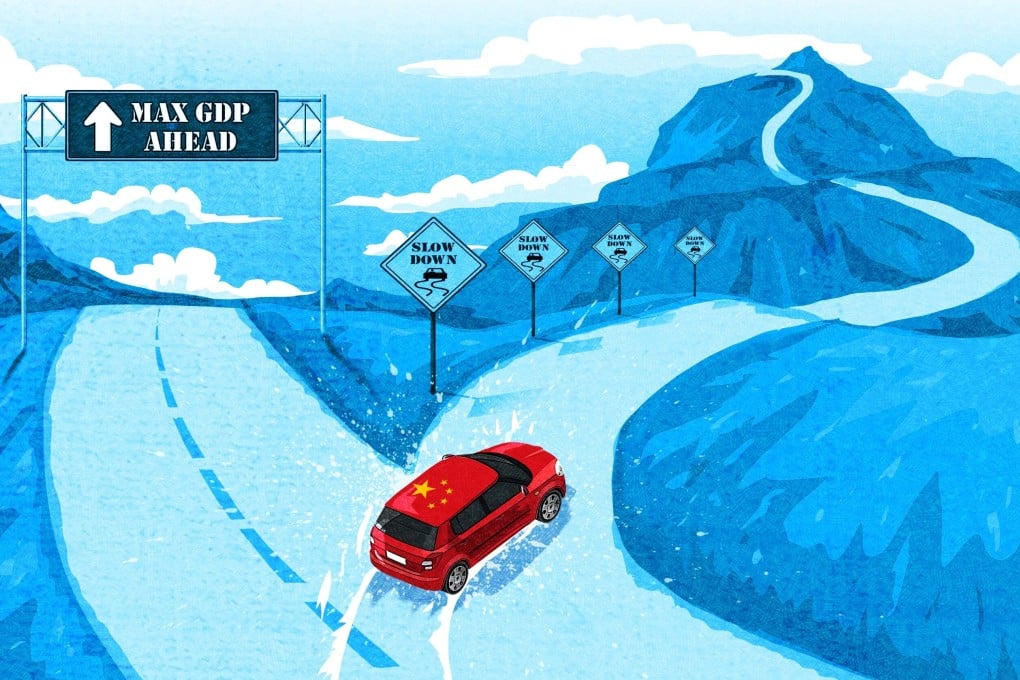

China’s economy downshifts to slower growth path as focus turns to social equality, national safety

- Beijing still wants to double China’s GDP by 2035, but ‘policymakers feel they need to address social issues to ensure social fairness and justice’

- Policy change prompts concerns that China is returning to a more nationalised economy that favours stability and protecting state enterprises

This is the first part in a series of stories looking at China’s economic outlook in the second half of 2021 as it continues its recovery from a coronavirus-hit 2020.

As US-China relations continue to deteriorate, Beijing is making a major policy shift towards social and economic governance that looks to be setting up a long-term decline in the nation’s corporate productivity and economic growth, according to analysts.

For starters, a number of restrictive factors – including demographic constraints on consumption, climate constraints on manufacturing, and macro constraints on monetary and fiscal policy – suggest China is facing a downshift to a slower growth path, said Richard Yetsenga, chief economist at ANZ Bank.

After China’s sharp economic recovery in the year’s first half, some economists now expect second-half economic growth to drop to about 5 to 6 per cent, year on year. And analysts say that could also be the full-year growth rate for 2022 – roughly the same growth path the country was on at the end of 2019, pre-coronavirus.

“China’s policy U-turn is tectonic,” Yetsenga said. “If tech is unable to sustain China’s high rate of growth, the focus will shift back to manufacturing and consumption. But both are facing structural challenges of their own.”