Chained Chinese mother puts spotlight on the country’s staggering gender imbalance

- Images of a mother chained by the neck in a tiny room in Jiangsu province have stoked debate about human trafficking and the country’s rural gender imbalance

- Demographers say her plight offers a peek into the complexity of marriage in rural China, which is still grappling with effects of the country’s one-child policy

Shackled by her neck and locked up all day in a squalid shack, video footage of a mentally-ill woman imprisoned by her husband has cast a shadow over the festive mood created by Beijing’s Winter Olympics.

The woman, surnamed Yang, has become a source of concern and outrage in China after video emerged of her grim living conditions in a village in Feng county, Jiangsu province.

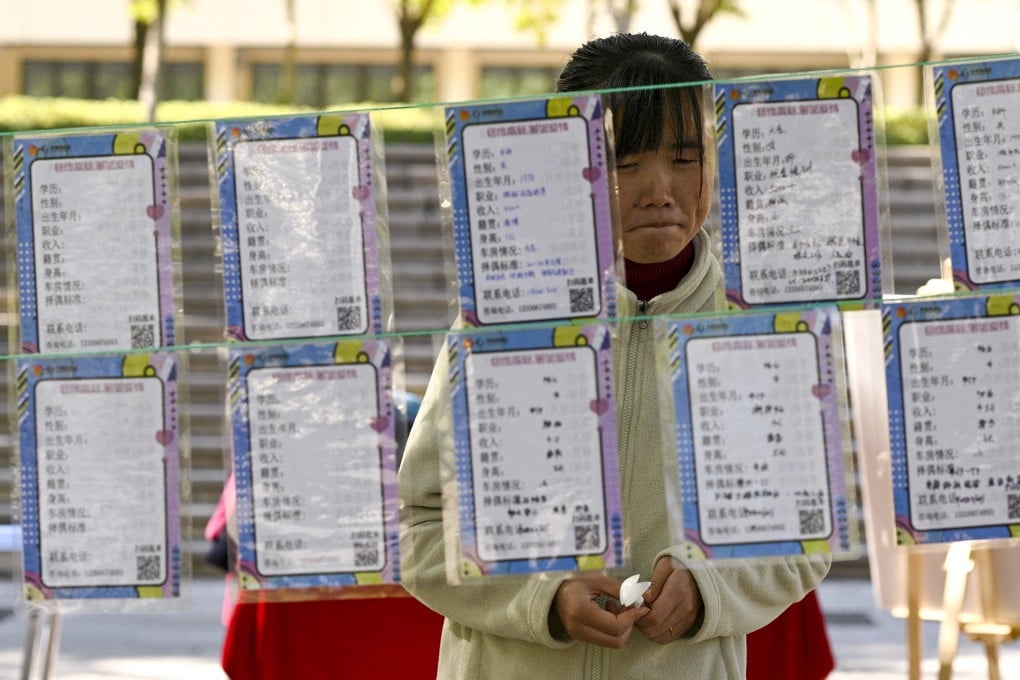

After repeated denials, local authorities finally acknowledged the possibility of human trafficking in Yang’s case on Thursday, while demographers say her plight offers a peek into the complexity of marriage in rural China, where traditional values such as a preference for sons and the decades-long one-child policy have resulted in a staggering gender imbalance.

The problem of tens of millions of bachelors caused by decades of one-child policy, is unsolvable

“The problem of tens of millions of bachelors caused by decades of one-child policy, is unsolvable,” said Yi Fuxian, a demographer and senior scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.