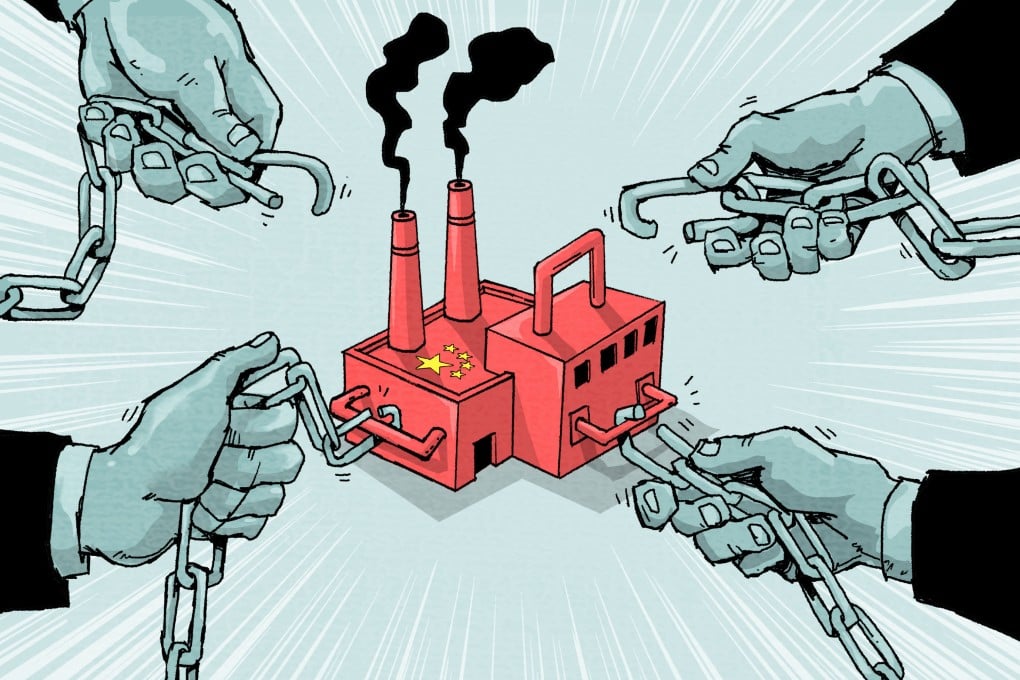

China’s manufacturers remain key to global supply chain, producers ‘ even more dependent’ on world’s factory

- Coronavirus-related restrictions and lockdowns have disrupted global supply chains over the last two years as many of them begin in China

- The US has long pushed for a so-called decoupling from China over fears of an over-reliance, but many find it hard to move away from ‘the world’s factory’

“There is no need to think of quitting China,” fabric exporter Raymond Xie was finally able to tell his clients earlier this month.

Like other veteran Chinese exporters, Xie’s “heart was torn with anxiety” after his factory operations at the start of the year were hit by coronavirus-induced supply chain disruptions.

“I was also worried that enormous orders from various industries might quickly leave China as a result.”

The tax rebates and other subsidies are enough to cover my recent losses. I can now promise my clients we are still the best cost-effective supplier

But Xie and his fellow exporters were finally able to breathe a sigh of relief when Beijing announced a series of tax relief plans earlier this month.

Xie was refunded nearly 90 per cent of the taxes he had paid in the first quarter of the year, which for him meant around 360,000 yuan (US$55,000) found its way back into his bank account.