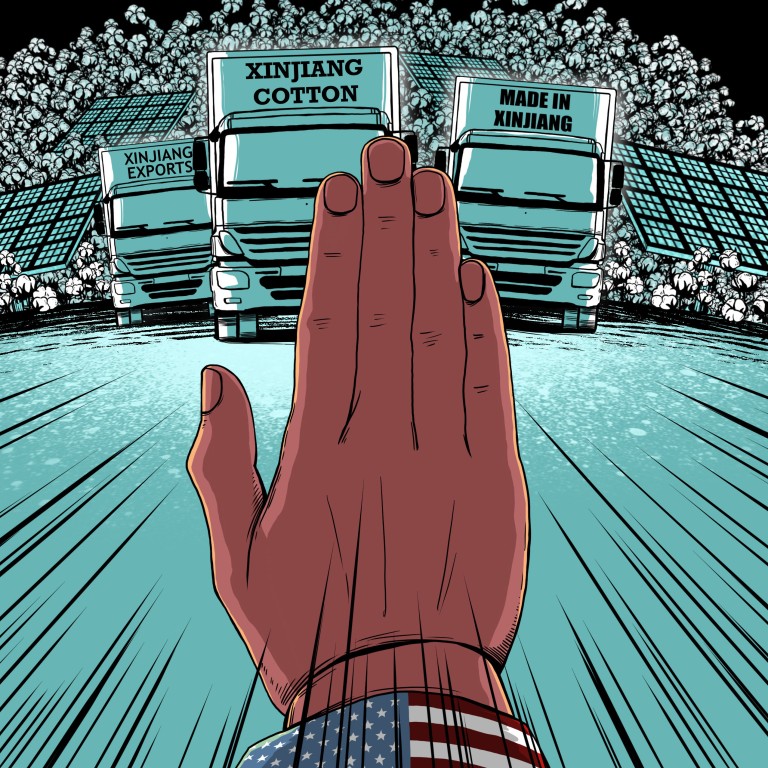

How the US’ Xinjiang labour law has crippled China’s cotton industry before even entering effect

- Chinese traders in Xinjiang say losses have been mounting for months, with vast inventories unsold as buyers shun what was once the world’s most expensive cotton

- Far-reaching implications from Uygur Forced Labour Prevention Act are expected to keep clouding trade relations between US and China, even as President Biden mulls tariff cuts

With the next harvest a mere three months away, cotton mills in China’s far west Xinjiang region are currently sitting on about 3 million tonnes of unsold inventory – a massive stockpile more than a million tonnes larger than it usually is this time of year.

That means more than half of the cotton harvested last autumn has yet to be sold.

“Xinjiang cotton used to be the most expensive cotton in the world. Now it has become the cheapest, and still no one buys it,” said the owner of a cotton-ginning mill in southern Xinjiang, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “Now I would lose 2,000 yuan (US$300) selling each tonne of cotton.”

This is owing to the impact of the Uygur Forced Labour Prevention Act – a United States law that effectively bans American imports of all products from Xinjiang unless conclusive evidence shows that no forced labour was involved in their production.

Even though the new law does not take effect until Tuesday, it is already having the intended effect on China’s cotton and textile industry.

“Downstream clients, especially those focusing on foreign markets, basically dare not use [Xinjiang cotton] any more, so they won’t buy,” the mill owner said.

What is going on in Xinjiang and who are the Uygur people?

Since President Joe Biden signed the act into law in December, its looming presence has gradually taken a mounting toll on several industries in China.

Thus, the pain at a single cotton mill in southern Xinjiang is felt across China’s entire textile industry.

[Banning Xinjiang cotton] basically means choking the supply chain of China’s textile industry

While Xinjiang does not export much raw cotton or yarn itself, most is consumed locally or sold to other provinces and then made into cloth, garments or other textile products for both domestic and overseas markets.

In 2021, Xinjiang’s annual cotton output was 5.27 million tonnes, accounting for 91 per cent of the nation’s total production, according to the China Cotton Association. Last year, 67 per cent of cotton consumed across the country was from Xinjiang.

“[Banning Xinjiang cotton] basically means choking the supply chain of China’s textile industry,” the cotton mill owner said.

Theoretically, US importers can still buy goods from Xinjiang, by providing the aforementioned evidence of no forced labour, but therein lies a bit of a catch-22. Since independent auditing is not available in the region, fulfilling such a requirement is virtually impossible, according to industry insiders such as Doug Barry, vice-president of communications and publications with the US-China Business Council.

“The law will essentially act as a trade embargo against goods with input from Xinjiang,” Barry said.

Germany, Britain and US press China over new Xinjiang human rights abuse cache

According to a survey by the China National Cotton Information Centre in early June, the rate of machines actually turned on at textile factories across the country was 79.7 per cent, a year-on-year decrease of 13.3 percentage points.

Meanwhile, with Southeast Asian countries resuming production capacities this year, avoiding Chinese suppliers has become much easier for US apparel importers, according to experts.

“Some [Chinese] companies have even lost up to 30 per cent of their orders,” said a report earlier this month by consulting firm Beijing Cotton Outlook. “According to corporate feedback, some major American apparel brands may no longer place orders from China in the future.”

International brands all want to continue their business with the US

Although the act theoretically applies only to exports to the US, the boycott from international garment brands has helped expand the law’s sphere of influence beyond US territories, said Tao Jingzhou, an international arbitrator who has practised in Beijing, Hong Kong and London.

“International brands all want to continue their business with the US,” Tao said.

For the world’s largest textile producer and exporter, the far-reaching impacts of the act should not be ignored, according to Liu Kaiming, a supply-chain specialist and founder of the Institute of Contemporary Observation think tank and action group dedicated to labour development and corporate social responsibility in China.

The value of China’s textile and apparel exports exceeded US$300 billion last year – accounting for nearly 10 per cent of all Chinese exports – with only US$30 billion to US$40 billion worth of raw materials needed to be imported, Liu added.

European Parliament passes landslide vote on alleged Xinjiang rights abuses

“In the textile and apparel export industry, the European and American markets bring considerable profits. If orders from Europe and the American market continue to contract, it means that China’s textile and apparel export enterprises will no longer be profitable,” Liu said. “It will just result in a growing number of Chinese enterprises reducing their production capacity or even shutting down.

“This has a huge and terrible impact on China.”

And while downstream manufacturers have been trying to adapt to the shift – such as by refining the raw-material procurement processes by using Xinjiang cotton entirely for domestic demand, and imported cotton for export orders – it is unlikely that the Chinese domestic market will be able to absorb all of the excess capacity from Xinjiang, industry insiders said.

“The domestic market can consume only about 3 million tonnes [of cotton] each year, at most,” the Xinjiang cotton mill owner said.

That total is a little over half of the annual output of the region, and it’s nearly the same amount of unsold cotton taking up inventory space at Xinjiang cotton mills by the end of May – 3.3 million tonnes, according to figures from Beijing Cotton Outlook.

But while Xinjiang cotton has essentially been crippled by the US law, not all industries with supply chains in Xinjiang have been hit as hard, even as uncertainties and risks remain.

That includes China’s polysilicon industry. The shiny, high-purity form of silicon is what solar panels use to convert sunlight into electricity. In China, that industry is centred in Xinjiang, but it has still managed to maintain an upper hand in the supply chain, despite the new US law, because only a small portion of it goes to the US.

“For the whole [polysilicon] industry, raw-material supplies have been a seller’s market for the past of couple years, and it will stay this way for at least three to five years,” according to a source at one of China’s largest producers of solar panel parts, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

“So, the impact [of the act] on companies’ profits is nonexistent, let alone affects the companies’ survival.”

China accounted for 75.3 per cent of global polysilicon production in 2021, according to the China Nonferrous Metals Industry Association.

China urges solar firms to fight against US, India trade blocks

Xinjiang’s abundant mineral and solar resources, as well as vast stretches of uninhabited land, make it the ideal location for the solar panel industry, and almost half of the world’s polysilicon can be traced back to the region.

And given that the US solar industry still remains reliant on China for supplies, many producers of those supplies have already started to circumvent risks by locating new capacities outside Xinjiang, while existing facilities in the region look to focus on supplying the domestic market, according to Dennis Ip, an energy analyst at Daiwa Capital Markets Hong Kong.

Some major Chinese producers of polysilicon, such as Xinte Energy and Daqo New Energy, which own Xinjiang-based manufacturing plants, are investing billions of yuan in new projects in China’s Inner Mongolia autonomous region, according to public records.

However, even if the polysilicon is not sourced from Xinjiang, imports of solar products from China remain at risk of being subject to detention by US customs, as the sourcing information is hard to verify, according to operational guidance for importers that was released by US Customs and Border Protection last week.

The potential risks have prompted some American companies in the solar industry to pay tens of thousands of dollars for relevant consulting work and traceability audits, noted a supply-chain-traceability expert on condition of anonymity.

In the first quarter of the year, the top export destinations of Chinese solar modules were the Netherlands, India and Brazil, according to a report by the China Chamber of Commerce for Import and Export of Machinery and Electronic Products.

But with European Commission lawmakers also debating a similar ban, the uncertainties swirling within China’s polysilicon industry remain considerable.

“European [solar] companies are also really wary of this,” said the traceability expert. “I had a lot of clients say to me, ‘we know we’re not importing into the US, but let’s act like we are, just so we are reaching the highest barriers and hurdles, in terms of regulations, so we know we can comply with that’. Because there might be a chance of something similar happening in the European Union.”

Dozens of countries call out China at UN over Xinjiang ‘abuses’

What about US trade tariffs?

Outside of what is happening with Xinjiang, there could be a glimmer of hope at the end of the tunnel for Chinese and US traders who find themselves at the mercy of political manoeuvring and trade-policy adjustments.

The benefits of lifting such tariffs would be far from able to offset the impact of the new Xinjiang law, but there are still upsides to doing so.

“The clamouring to remove some of the tariffs is growing louder,” said Barry with the US-China Business Council. “If they are lifted, China should reciprocate, perhaps creating the opportunity for high-level discussions about trade and other issues. Official communication channels [between Washington and Beijing] seem to consist primarily of diplomats yelling talking points at each other. Now’s the time to resume serious, pragmatic dialogue.”

‘All options’ on table in China tariff review, US seeks plan ‘that makes sense’

Eric Zheng, president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai, said removing the tariffs would benefit both countries.

“American consumers would have access to more affordable products from China, and Chinese exporters would be able to reduce their costs,” Zheng said.

Among those keen on seeing the tariffs removed is footwear producer Wang Jie. He said he has long felt powerless as a small trader in what has become a drawn-out tug of war between China and the US.

The geopolitical tensions, he added, have been overwhelming at times.

Wang expanded the production capacity of his factory last year, but his business has been struggling in the last couple of months, losing orders to Vietnam.

“I certainly hope that the tariffs can be lowered,” Wang said. “Then it means we again have an absolute advantage over Vietnam – orders will not leave China.

“But we can only react passively to all of the changes, whether they be tariffs brought by the trade war, or shifting of orders brought by international relations.”