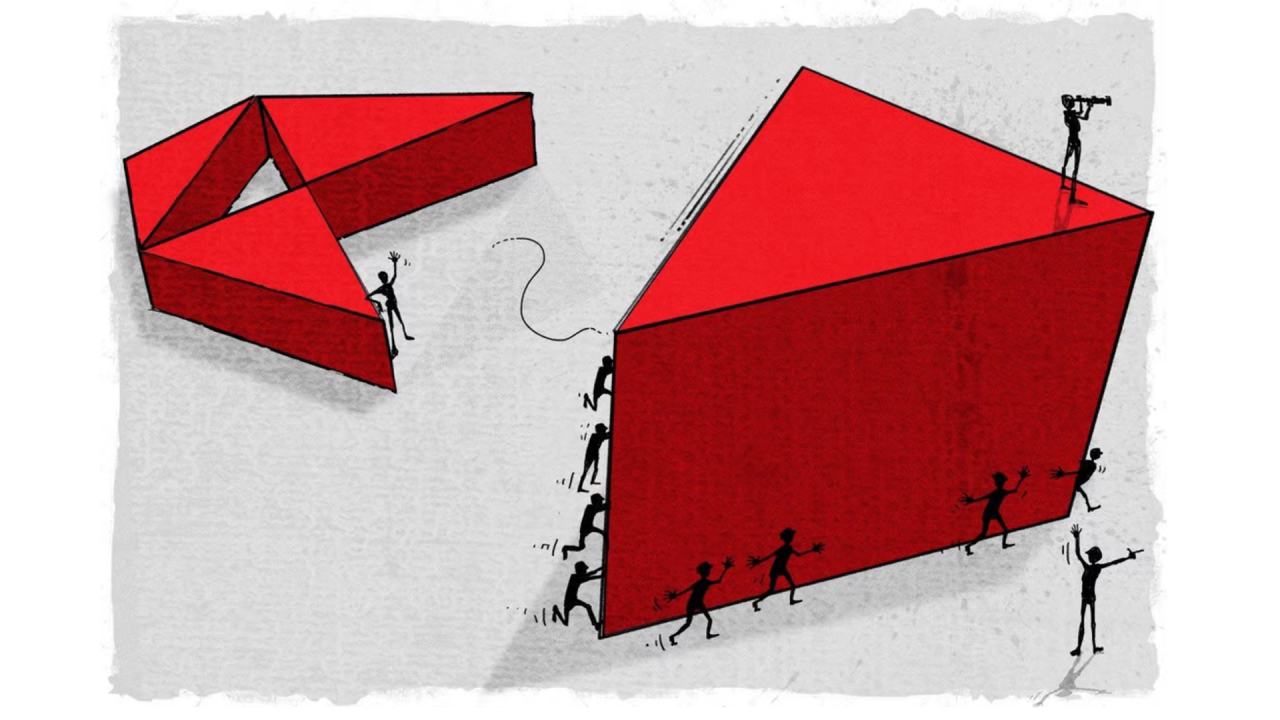

China’s regional banks tarnished by allegations of crimes, bad loans and excessive risk

- The coronavirus pandemic and subsequent virus controls have taken a huge toll on regional finances and exposed scores of bad loans in the process

- The province of Liaoning epitomises the precarious nature of China’s regional banking system after years of issuing loans with loose or no credit checks

After more than a decade of freewheeling growth riding the winds of government stimulus, China’s small banks have become a financial burden for local authorities and the target of a national anti-corruption campaign.

The situation is especially severe in less developed regions, like Liaoning province, where the coronavirus pandemic and subsequent virus controls have taken a huge toll on regional finances and exposed scores of bad loans in the process.

Xiao Yuanqi, the vice-chairman of China Banking Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC), said last week financial risks associated with small- and medium-sized banks (SMBs) were generally controllable, but “problems still exist” and some lenders are suspected of committing crimes.

Disciplinary action and criminal coercive measures have been taken against 63 SMBs executives since last year, according to a CBIRC briefing in May.

The province has 75 SMBs, including city-based commercial and rural banks.

Over the years, many small Chinese lenders have freely issued loans to major local companies with loose or no credit checks, creating room for corruption, while attaching their liquidity to the financial health of certain firms, according to experts.

“Once these companies can no longer pay the interest, these banks run out of cash immediately,” said a Liaoning-based auditor on condition of anonymity.

Occasional rumours of capital crunches have hung over small banks in Liaoning since 2019, sometimes leading to a rush of deposit withdrawals.

The non-performing loan ratio – which measures the rate at which bank loans are not repaid – in Liaoning’s financial sector was 5.11 per cent in 2020, according to the official figures released by the provincial government in January.

The overall ratio for the commercial banks in China was 1.91 per cent in the same year, according to CBIRC data.

The Liaoning provincial government has tried to curb risks by consolidating small banks into a single government-owned lender.

But the effect of the merger has been questionable. The new bank’s first annual report showed that last year its revenue was negative 475 million yuan (US$70.8 million), with a net loss of 1.19 billion yuan. The non-performing loan ratio was 6.02 per cent.

The second phase of the plan is expected to take place this year, with Bank of Huludao and Bank of Chaoyang merging, the auditing source said. But it is unclear whether it will proceed.

“Nobody knows whether [the merger] would work, it is essentially delaying the risk exposure via issuance of government bonds,” the source said.

The Liaoning government has issued three rounds of special purpose bonds to recapitalise SMBs since last year. The first round worth 10 billion yuan in May 2021 was used for the launch of Bank of Liaoshen.

The second issuance of 9.6 billion yuan in September last year was to replenish the capital of 30 rural credit co-operatives and seven rural banks. While the third, which totalled 13.5 billion in April, was for five more city banks, according to information disclosed by ChinaBond, a central securities depository for government bonds.

The issuance of such bonds leaves local governments directly exposed to local financial sector risks and they are likely to suffer losses on the investments, Moody’s credit rating agency said in a report last year.

The associated risks could transmit to [regional and local governments’] balance sheets directly

The issuance of such bonds leaves local governments directly exposed to local financial sector risks and they are likely to suffer losses on the investments, Moody’s credit rating agency said in a report last year.

“The associated risks could transmit to [regional and local governments’] balance sheets directly, especially for regions that are financially stressed and face greater banking risk, such as provinces in the west and northeast,” said Amanda Du, vice-president and senior credit officer Moody’s.

In a CBIRC briefing in May, an official said that the Liaoning government was formulating a plan to promote reform and resolve regional financial risks, Chinese media reported.

“The vast majority of financial risks in Liaoning are existing risks,” said the official, who was not identified.

“With the attention of all parties, new risks have been effectively contained, and existing risks are being dissolved or partially dissolved. It will take some time to curb the risks completely.”