China’s ‘rattled’ private firms with little confidence await signs, reassurances that some fear will not come

- From its zero-Covid policy and heavy-handed regulations to deteriorating international relations in a weakened global environment, China faces a ‘storm’ like it’s never seen

- Hard-hit entrepreneurs are stumbling through the dark, investor nerves are frayed, and all they can do is wait for what might come out of this week’s party congress

Wu Hai has been warning about the struggles faced by China’s private businesses for years, and he seems to have Beijing’s ear.

The founder of karaoke chain Mei KTV, Wu complained about the country’s business environment in an open letter to state leaders that was posted on social media in 2015. He was surprised when it prompted an official invitation to explain his suggestions to a select audience at the Zhongnanhai leadership compound in Beijing amid efforts to encourage start-ups and innovation.

Today, Wu has his sights set on the Omicron variant of the virus, which has compelled many Chinese cities to restrict people’s movements to curb its rapid spread. Investor morale has plunged, and for many, no light can be seen at the end of the tunnel.

Pandemic path to adulthood leaves young Chinese with ‘no desire to fight’

“China is now facing a ‘perfect storm’, with unexpected hits from four directions – the pandemic, deteriorating China-US relations, a weak global economy and strong regulation in an unfavourable economic environment,” Wu wrote on his WeChat account on October 9.

A vicious cycle has ensued, with hard-hit entrepreneurs becoming more reluctant to invest amid high levels of business uncertainty, he said.

“The erosion of confidence is the biggest challenge facing China,” Wu warned.

Contact-intensive service providers, such as restaurants, travel agencies and street vendors, have, in particular, been struggling during the rigid implementation of zero-Covid policies this year.

But big companies are also having a tough time. Many privately run property developers, including Evergrande, have defaulted on debts after regulators imposed strict financial requirements and restricted their fundraising channels as part of Beijing’s efforts to discourage speculation and take the heat out of the property market.

Big tech companies, a driving force behind China’s dazzling growth in the past, have been downsizing their workforces after the government launched high-profile antitrust probes and strengthened regulations on privacy protection and data security.

The Chinese mainland’s business conditions index, based on a survey of hundreds of companies by the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business, fell to 44 last month from 46.1 in August, languishing well below the confidence threshold of 50.

Similar to foreign investors, who have questioned Covid-linked disruptions and reconsidered China investment plans amid heightened geopolitical tensions, domestic entrepreneurs are watching closely to see if any new support measures, policy changes or even a new development direction are announced by the new leadership that is due to be selected at the Communist Party’s five-yearly national congress this week.

Xi warns of fierce storms ahead as he vows ‘incomparable glory’ for China

On top of regular complaints about rising costs, funding difficulties, and dwindling cash flows and overseas orders, an overriding question centres on how the new leaders will restore growth momentum in the world’s second-largest economy, and what role they see private capital playing in the next five years and beyond.

“Leftist noises often get loud during the transitional period,” said Wang Jun, a director of the China Chief Economists Forum, referring to the ideological push for a bigger state-owned economy and threats to eliminate private ownership.

“They have rattled the already fragile nerves of private firms,” he said, noting that investor expectations have been disrupted by the economic slowdown, external situation and regulatory campaigns.

Voices calling for the elimination of private ownership four years ago, most notably those of Renmin University professor Zhou Xincheng and finance professional Wu Xiaoping, recalled China’s ideologically driven past and fanned the flames of panic among the business community.

It only eased when President Xi Jinping promised, at a high-profile entrepreneurship symposium at Beijing’s Great Hall of the People in November 2018, that there would be no lack of resolve in encouraging, supporting and guiding non-public-sector development.

But Wang said Beijing’s push for better social welfare would not entail a replacement of the market economy that laid the foundation for China’s economic success in past decades.

China’s foreign firms, struggling to survive, brace for whatever comes next

Private enterprises mushroomed following China’s shift from a Soviet-style command economy in the 1980s, and they received a big boost when Chinese leaders decided at the party congress in 1992 to develop a socialist market economy and to embrace the world market.

The private economy is officially deemed significant because it contributes more than half of the country’s tax revenue, accounts for 60 per cent of the national gross domestic product, and dominates the hi-tech sector.

More than 405 million people worked for private companies or were self-employed in 2019, equivalent to about 29 per cent of the Chinese population, government data showed.

Analysts worry about anti-capital sentiment, even though China’s constitution acknowledged the role of the private economy as an important constituent of the socialist market economy in 1999 and pledged to protect private property in 2004.

Jia Kang, former head of the Ministry of Finance’s research institute and a political adviser, compared such leftist ideology to a small ghostly fire that kept haunting private entrepreneurs.

“It turned out to be very destructive,” he said in a speech late last month. “What will entrepreneurs think of such things? They would ask what on Earth the authorities plan to do. I think we must emphasise the central government’s guideline of the traffic-light mechanism: capital is neutral, and it is no longer bloody and dirty as described by Marx in Capital.”

Jia, now head of the Beijing-based China Academy of New Supply-side Economics think tank, warned that the erosion of investors’ confidence would directly affect their long-term business considerations.

“It would be significant to shore up confidence and guide expectations if the government could thoroughly protect intellectual property, promote entrepreneurship, rectify wronged cases, and release a batch of approved [private investment] examples as soon as possible,” he added.

There are definitely things Beijing can do to boost confidence, but that doesn’t seem very likely to happen

Houze Song, a fellow with the MacroPolo think tank at the Chicago-based Paulson Institute, said the current private sector difficulties have made such ideological debate more salient.

“There are definitely things Beijing can do to boost confidence, but that doesn’t seem very likely to happen, in my opinion,” he said, attributing the situation to the current preoccupation with politics. “There is little sign suggesting to me that Beijing will reset its economic policy.”

The number of private companies in China more than tripled in a decade to reach 47 million by the end of August – with 11.8 million added since the start of the coronavirus pandemic – and they accounted for 93.3 per cent of all enterprises, the State Administration for Market Regulation said last week, attributing the growth since the start of the pandemic to unprecedented efforts by Beijing to protect market entities and employment.

Private investment accounted for 56.9 per cent of total investment last year, more than in 2020, and the combined revenue of the top 500 private companies rose 9.1 per cent, year on year, to 38.3 trillion yuan (US$5.3 trillion) last year, the semi-official All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce said in a report last month. Eighty-seven of them registered revenue of more than 100 billion yuan, and 37 saw a net profit of more than 10 billion yuan.

‘Highly investible’ China woos foreigners but withholds what they want most

On the other hand, a private-enterprises prosperity index dropped to 100 in the second quarter of the year – the dividing line between expansion and contraction, and the second-lowest reading since the 86.5 recorded in the first quarter of 2020, the National Bureau of Statistics said.

Premier Li Keqiang has used many occasions in the past half year – from a field trip to Shenzhen to State Council conferences and meetings with foreign investors or diplomats – to offer reassurances about China’s economic-development priorities, its support for the private sector, and its commitment to an open-door policy and a better business environment.

Wu said confidence is the biggest asset for the private sector, but it will take a long time for investor confidence to be rebuilt.

“This can be started with high-profile government publicity that it will continue to centre on economic development and will insist on reform and opening-up,” he said. “Reassurances must also be given about the contribution of capital to the national economy.”

Answering a question from the Post at Saturday’s press conference, Sun Yeli, spokesman of the ongoing 20th party congress, said that entrepreneurs remain an important force that the Communist Party must rally behind and rely on in the long term, and that a traffic-light system is being introduced to ensure healthy capital development under the legal framework.

“This, we believe, will not hinder the growth of the private economy but actually be conducive to it,” he said.

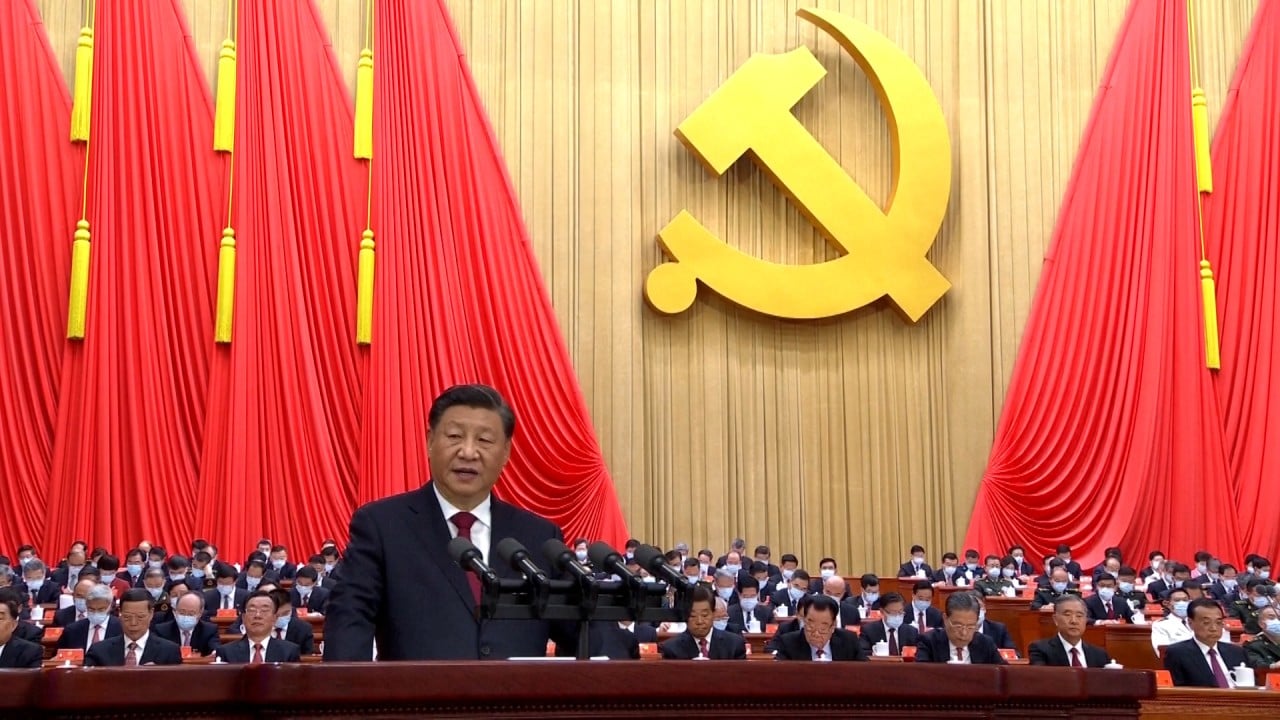

Xi also doubled down Beijing’s support for the private economy in his widely watched keynote report on Sunday during the opening ceremony of the party congress, vowing to cultivate a favourable environment for private enterprises, and to protect their property rights and the rights and interests of entrepreneurs in accordance with the law.

“We must unswervingly encourage, support, and guide the development of the non-public sector, and we will work to see that the market plays the decisive role in resource allocation,” Xi said.