Explainer | How much is China’s economy struggling and how much worse can it get?

- World’s second-largest economy has been facing setback after setback, and it is unclear whether recent GDP figures will mark the start of a sustainable recovery

- China’s restrictive zero-Covid policy, property downturn and waning confidence among consumers and investors remain outsized economic threats

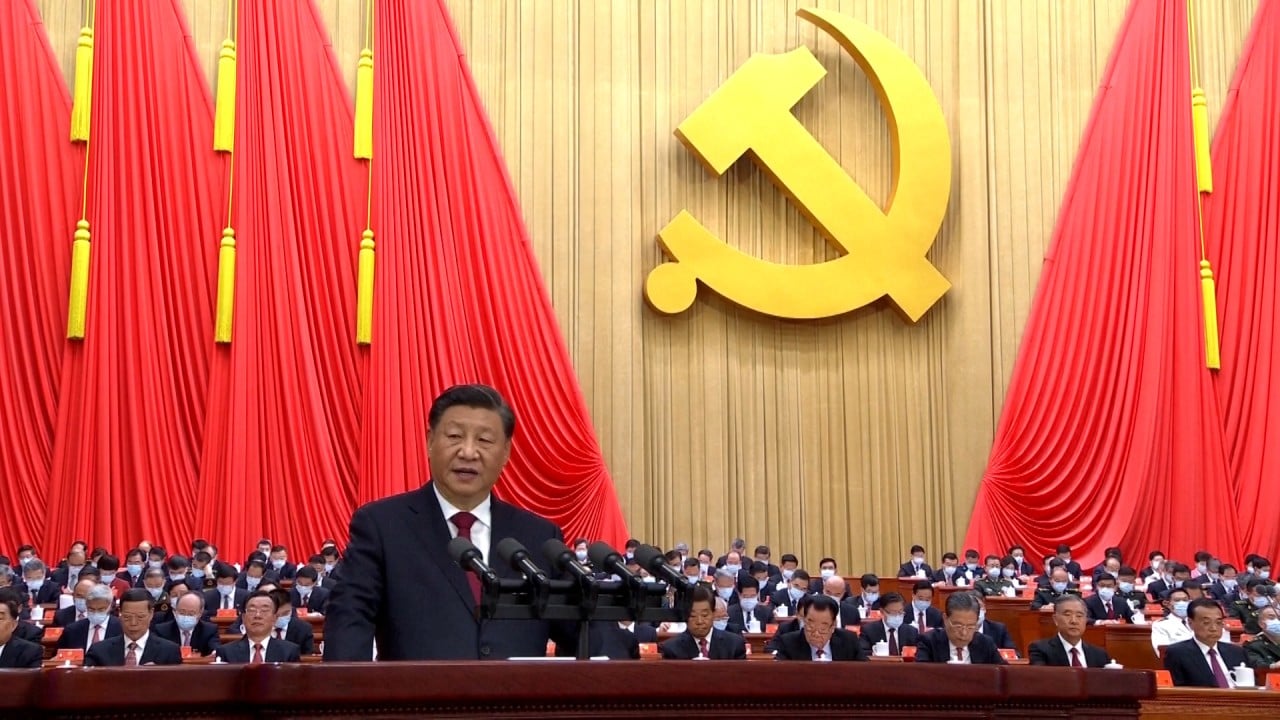

China’s economy is experiencing a mild rebound and could be poised to receive a boost of momentum with the swearing-in of a new leadership line-up.

The world’s second-largest economy faces some stiff headwinds, including a property downturn, weak private investment, waning consumption and business confidence, plus external challenges that are only expected to intensify in the coming years.

How bad is China’s economy?

The major economic headache includes a plunge in the property sector that will continue to weigh down growth, while the still-high level of jobless young adults poses a threat to social stability.

Are there any bright spots for China’s economy?

The January-September GDP growth of 3 per cent is certainly lower than in the past, but it is rebounding and still better positioned than major economies.

China’s industrial system performed well, and it remains a key supplier to the global market, with a 12.5 per cent rise in exports seen during the January-September period.

The better-than-expected third-quarter performance allowed UBS to revise up its 2022 growth estimate by 0.5 percentage points to 3.2 per cent while keeping its next-year growth estimate at around 4.5 per cent.

This is much lower than the 8.2 per cent rate in the US, 9.9 per cent in euro zone, and 10.1 per cent in Britain, and it provides China with more wiggle room in its monetary policy loosening.

What are the future challenges for China’s economy?

The immediate challenge faced by the world’s second-largest economy is how Beijing’s policymakers reconcile growth with their restrictive zero-Covid policy. The pace of such an adjustment is key to forecasts for the coming year.

Ding Shuang, chief Greater China economist with Standard Chartered Bank, attributed the weaker-than-expected results from Beijing’s stimulus measures this year to coronavirus disruptions, and said that a scientific approach could propel the economy back to previous levels of growth.

However, he warned that the fiscal room will be smaller and will subsequently affect infrastructure spending. China’s augmented budget deficit for January-September reached 6.5 trillion yuan (US$894 billion), compared with 2 trillion yuan in the first nine months of last year.

Mizuho economist Serena Zhou said that concerns about China’s forth-quarter growth look to persist amid the challenging coronavirus policy, persistent property sector weakness and a diminishing growth outlook for developed economies – factors that led to Mizuho lowering its 2022 China GDP forecast to 3.3 per cent from 3.7 per cent.

Another concern is how the new economic line-up deals with exports and efforts to contain China technologically.