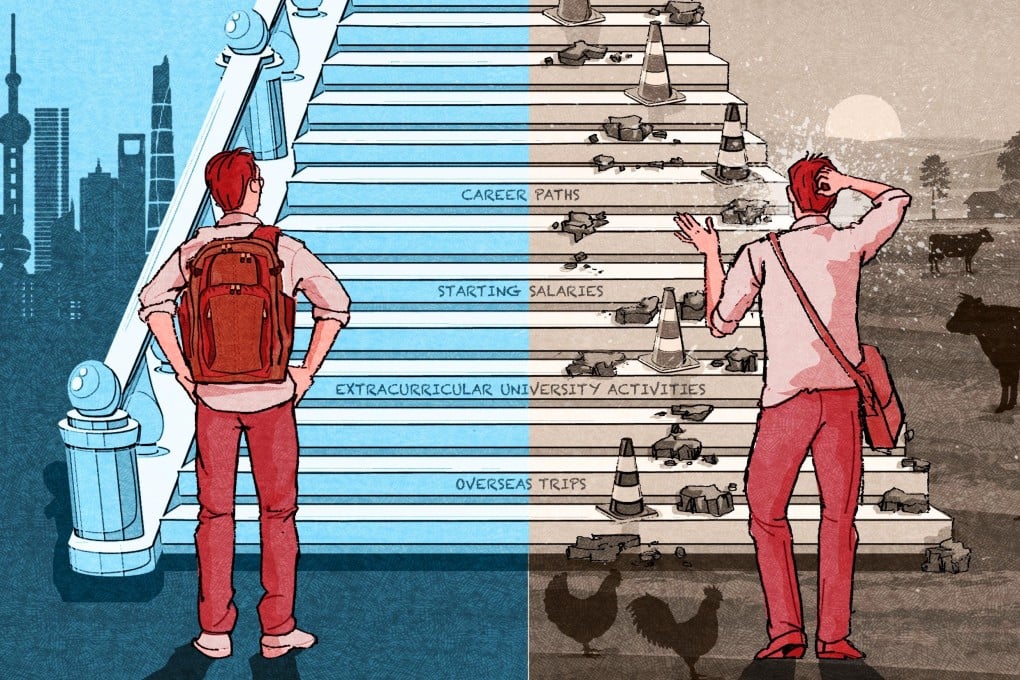

China’s rural students face upwards mobility battle as class obstacles limit chance to leap forward

- Students from rural areas often struggle to afford additional costs at university, including overseas trips and extracurricular activities

- This can lead to students from rural backgrounds not reaching the same level or starting salaries as their urban counterparts

Xinjiang-native Ma quickly discovered her choice of studying Hungarian at university was not only tough academically, but also financially – two factors which would weigh on her chances to gain employment in China’s increasingly competitive job market.

A 21-year-old Ma was unfamiliar with the central European language when she made the decision from her home in a small county in China’s northwest in 2018 ahead of her move to a university in Beijing.

“In my [third] year, all the other students in my class, except me, studied abroad for a year, I couldn’t afford this trip and my grades didn’t meet the requirements for the scholarship [to pay for the trip],” said Ma, now 24, who initially took out a loan to be able to study in Beijing.

Research has found that students from rural areas in China often struggle to afford additional costs at university, including overseas trips and extracurricular activities, which can mean they do not reach the same level or starting salaries as their urban counterparts.

We have a saying that ‘the children of farmers can only be farmers’, I thought it was ridiculous as a kid, but now I think it expresses the difficulty of class mobility in a simple and crude way

Those coronavirus prevention measures have also now prevented her from returning to Beijing to continue her studies and potentially take up an internship having returned home for her summer holiday.