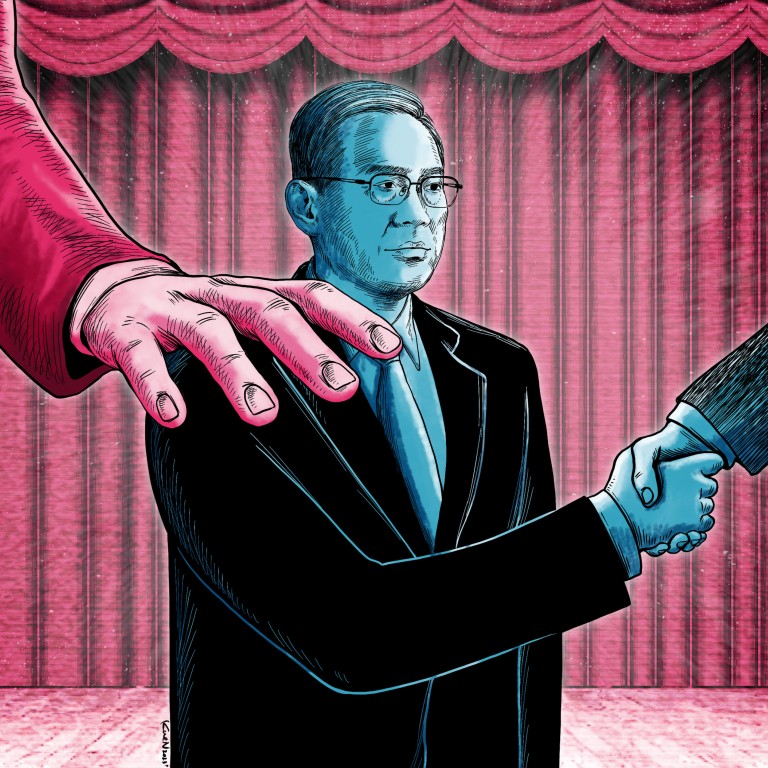

China’s ‘two sessions’ 2023: how will Li Qiang’s pro-business past and pragmatism help tackle China’s growing pains?

- Analysts say that holding the trust of President Xi Jinping will grant Li Qiang a higher degree of autonomy in economic affairs, allowing him to take bold actions

- Li’s expected elevation to premier would make him the first such Chinese leader in three decades to have no previous experience in the central government or in west China

With Li Qiang poised to take the premiership baton that will put him firmly on track to run the world’s second-largest economy, the onlooking crowd is already debating and dissecting the big questions over his would-be role, work style, policies and priorities.

Historically, the 63-year-old has shown himself to be a pragmatist with a strong business-oriented mindset, but his relatively low profile until recently has left the market scrambling for signs or indications of how he would manage far more sophisticated domestic issues while countering US decoupling pressure at the central-government level.

Li, as the most pro-business politician in President Xi Jinping’s inner circle, would shoulder the responsibility of shoring up the economy to previous levels of growth, defusing immediate risks, tapping into long-term growth potential and elevating China into a high-income economy during his tenure.

Many overseas analysts believed that Li, who was Xi’s de facto chief of staff in Zhejiang province from 2004-07, will mainly play the role of implementer, rather than be tasked with reshaping the country’s development course.

‘Two sessions’: can new premier stir market optimism in China reopening bets?

“His main strengths are his long work as a close adviser to Xi Jinping,” said Andrew Collier, a China analyst with Global Source Partners.

Domestic scholars believe that holding the president’s trust will grant Li a higher degree of autonomy in economic affairs, allowing him to take bold actions to address the most pressing issues, such as shoring up private confidence.

“He has the room to do something great, but this all must be done under Xi’s overriding thoughts or within his tolerance,” said an independent Chinese economist who declined to be identified given the politically sensitive nature.

In addition to lingering economic headaches such as high levels of local-level government debt, a property crisis and the uneasiness of both investors and consumers, the No 2 leader in the Communist Party will face an urgent need to prevent overseas orders from falling, while also considering contingency plans for if relations keep deteriorating with some of China’s top export destinations and sources of technological expertise.

“He was a strong advocate for further opening the market to foreign investors and urged local bureaucracy to create a business-friendly environment when he was at the helm of Shanghai,” said Wang Feng, the chairman of Shanghai-based financial services group Ye Lang Capital.

“He is likely to give businesses, from home or abroad, greater freedom in conducting cross-border trades while requiring government officials to further cut red tape to serve the companies.”

Analysts also suggest that the economic rebound from a post-Covid reopening will help alleviate the pressure on Li to stabilise the economy, allowing his cabinet to devote more effort to addressing pressing issues such as lifting investor confidence, curbing the high jobless rate among youth and reversing weak private spending.

As China’s white-collar staff fear firings, grads face unimaginable challenges

However, questions remain over how he might reconcile his policies with Beijing’s long-term targets of self-reliance and common prosperity, and how far he could push the reform of the fast-ageing and debt-ridden economy to bring back sustainable growth in the face of external headwinds.

“The defining question of 2023 will be whether the shift in policy and rhetoric is merely a short-term tactic by the Chinese government to shore up growth,” noted a report last month by China Pathfinder, a project launched by the Atlantic Council and Rhodium Group.

Chinese authorities, who have already shifted their work priorities from pandemic prevention to economic growth, are expected to set a GDP target of above 5 per cent at the National People’s Congress session this month.

As a native of Zhejiang’s Wenzhou city, which took the lead in the development of its private economy from the late 1970s, Li passed a variety of economic tests while helping lead rich eastern provinces.

He openly said that officials who only heed superiors’ advice to carry out work were not welcome

Long billed as a loyal enforcer of President Xi’s policies, Li displayed a can-do spirit in Shanghai, pushing local officials to react quickly to address companies’ needs, as a means to fire up the local economy.

To make Shanghai’s business environment more friendly to foreign and domestic businesses, he required that officials reduce the time needed for a new company to complete its business registration, obtain a manufacturing license and gain access to electricity.

“He openly said that officials who only heed superiors’ advice to carry out work were not welcome,” said one of the officials who asked not to be identified. “He told officials to be reactive to companies’ requests and to serve them wholeheartedly.”

Li was behind a series of hallmark events, including a broad upgrade in Wenzhou’s growth model, the rise of Zhejiang’s internet-based economy, the rapid building of Tesla’s super factory in Shanghai, and the establishment of the city’s science-tech board to fund the “new economy”. He had a decades-long commitment to a better business environment, to embracing the new economy and to unleashing entrepreneurship.

Young Chinese say real estate isn’t the nest egg it was all cracked up to be

Entrepreneurs who knew him in his early years were impressed with his “listening ears” and “down-to-earth and pragmatic” mindset, expecting more practical measures to be delivered over the next five years, such as further reduction in government approvals, easier market access, and greater financing support for small and private businesses.

Li’s transformation of Wenzhou, the country’s 27th-largest city economy, two decades ago provided some clues about his plans to break existing economic bottlenecks.

He put particular emphasis on improving the business environment, courting direct investment and making technological upgrades.

He gathered more than 6,000 local cadres at the Wenzhou Gymnasium in August 2003 to inaugurate his “efficiency revolution”, which tasked bureaucrats with cutting red tape and streamlining government approvals.

The first World Wenzhouese Conference, with a congratulatory message from Xi, then Zhejiang party boss, was held two months later to lure back overseas Chinese for investment.

The city pledged to offer brands local advantages while encouraging local firms to carry out technological innovation, striving for independent intellectual property rights, core technologies and a leap from “Made in Wenzhou” to “Created by Wenzhou”.

Two company bosses in Wenzhou, who asked not to be identified, said the incoming premier displayed the resolve and courage to bolster the development of privately owned businesses from 2002-04 when he was the top boss of the city.

“He knew how to inspire business owners to increase their investments in production and sales,” said one entrepreneur in Wenzhou. “It was, by all means, a bold move by a local party boss to give priority to non-state-owned companies in chasing economic growth.”

Wenzhou, known as the capital of private enterprise on the mainland, spawned thousands of super-rich individuals since the 1990s, as local businesspeople with high-risk appetites tapped into the breakneck economic growth to strike it rich by heavily investing in properties, coal mines and manufacturing.

We need to reduce the government’s intervention in microeconomic activities … retract the overstretched hands

Its controversial underground banking sector effectively propelled the local economy in the early 2000s until it was undermined by a series of frauds and defaults amid a lack of regulatory oversight.

When governing Zhejiang, the country’s fourth-largest provincial economy, he pledged to make it a province with the country’s fewest government approvals, highest efficiency rate and best investment environment immediately upon being elected as governor in early 2013.

Li’s vision of government, as disclosed in a 2013 interview with Caixin, is one with limited power, that is well-functioning and efficient, and which strives to shift from the role of housekeeper to servant.

“We need to reduce the government’s intervention in microeconomic activities, put the government’s hands back in place, put away the restless hands, retract the overstretched hands, and do what needs to be done,” he said at that time.

Li’s pro-business image is also regarded as vital to reviving the severely diminished private confidence.

China’s 50 million private firms need ‘continuity, stability’ to aid recovery

Private investment rose only 0.9 per cent last year, far below the 5.1 per cent growth seen in fixed-asset investments, suggesting that investors took heavy hits during the pandemic and remain concerned about the outlook.

During his tenure as a provincial leader, Li was a frequent speaker on occasions with entrepreneurs. He openly talked about his admiration of China’s top internet entrepreneurs, including Tencent founder Pony Ma and Baidu founder Robin Li. In the prologue for the book of Wang Jian, then chief technology officer of Alibaba, he also expressed appreciation for the chats with leading entrepreneurs and visionary technologists. Alibaba is the owner of the South China Morning Post.

Addressing the Zhejiang Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai in December 2014, Li said: “If entrepreneurs do their jobs well, life would become much easier for government departments. Therefore, I am here today to ask you all to do your job better. Of course, one of our responsibilities is to create a better environment for your work.”

Li’s appointment would make him the first such leader in three decades to have no previous central-government nor west-China experience. His predecessors – Zhu Rongji, Wen Jiabao and Li Keqiang – spent five years as executive vice-premier before being elevated to the top economic job.

China’s problems with slower growth, a free-falling property market and gradual decoupling may force Xi to accept modest capitalist reforms

His upcoming premiership comes as China’s exit from its zero-Covid strategy and the nation’s reopening have already lifted market estimates for the country’s economic performance. However, the market is also debating whether China’s current rebound is sustainable.

“The loss of confidence is likely to prove a more intractable problem that won’t be solved by simply lifting Covid restrictions,” said Enodo Economics, a macroeconomic and political forecasting company in London.

Speaking at the tone-setting central economic work conference in December, President Xi ordered senior economic cadres to “show clear attitude” over China’s pro-market reform and to institutionalise the equal treatment for private and foreign-funded enterprises. The Chinese leader also vowed to lure more high-quality foreign investment and to provide the best possible conveniences for visiting foreign executives.

“China’s problems with slower growth, a free-falling property market and gradual decoupling may force Xi to accept modest capitalist reforms in local jurisdictions, but the state model will predominate in Beijing,” said Collier with Global Source Partners.

Chinese firms try ‘decoupling’ from China as US business climate turns hostile

Fraser Howie, co-author of Red Capitalism: The Fragile Financial Foundations of China’s Extraordinary Rise, also warned that the alarm bells going off in the private economy haven’t abated because the regulatory framework around control of tech and the private sector remains very much in force.

“The worst may be over, but that doesn’t imply at all that we have wound back the clock,” Howie said.

The absence of young reformers also has some foreign investors concerned.

“Since politics is the driver, then I really worry about the direction of economic policy, not only in the framing of it, but also in the delivery of it,” he said.

Li’s expertise in fostering the new economy may be vital for the transformation of China into digital economic power.

Meanwhile, his bringing of the World Internet Conference, a Beijing-led platform on internet business and affairs, permanently to Wuzhen, Zhejiang, under Li’s leadership has bounded information technologies and the internet together with its deep-rooted private economy, and turned the province into a highland of the new economy.

Chips and EVs are bright spots in China’s tech funding slump

Li visited Microsoft, Boeing, Google, Tesla, Illumina and Qualcomm after the China-US Governor’s Meeting in September 2015, and he invited them to invest or cooperate with businesses in the eastern province, vowing to “align to international advanced levels, be problem-oriented and demand-driven, and accelerate the construction of an innovation system that leads future development”.

However, the ongoing US tech decoupling, with increasing restrictions imposed on high-end chips and other hi-tech goods, may thwart his ambitions, analysts said.

The US Department of Commerce has put hundreds of Chinese companies, including the widely watched telecoms giant Huawei, on its so-called Entity List, barring them from accessing American parts, technologies and markets.

“Li has rich experience in managing the country’s major local economies,” said Qiao Yide, vice-chairman of the Shanghai Development Research Foundation.

“He faces a difficult task of getting China’s economy back on track, and the business community is pinning hopes on his pro-opening attitude to fuel economic growth, particularly with detailed policies to support the development of privately owned businesses.”