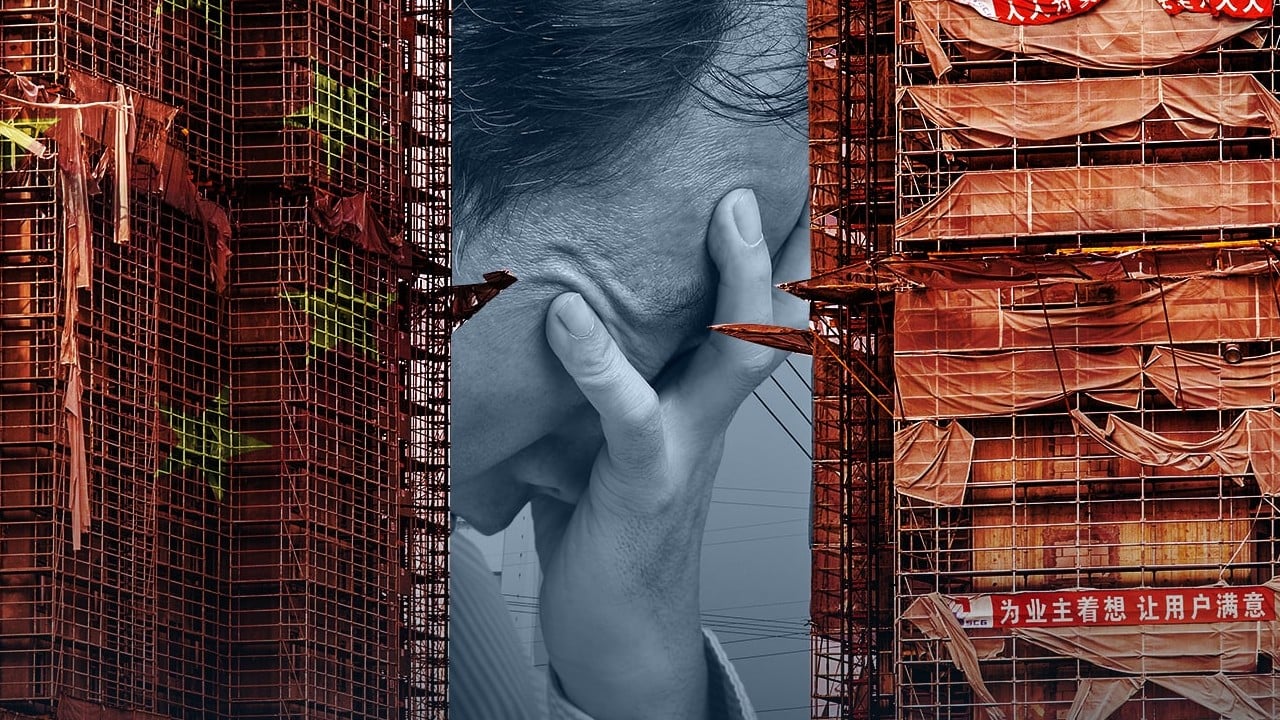

China’s paltry support for private sector leaves its economic backbone in more dire straits than state firms

- Beijing’s support for the private sector is increasingly being perceived as lip service in the absence of more action

- With state giants faring better than their private counterparts, an official charm offensive could be wearing thin, and it threatens to slow China’s post-Covid recovery

Despite receiving more orders than last year, a literal door maker in China’s southwest is struggling to open enough figurative doors to make ends meet.

Besides cutting labour costs, the company – a privately held industry leader in the region – has opted to cut profit margins to grab a bigger market share amid an uneven recovery of the world’s second-largest economy.

Though its revenue has been growing so far this year, the company’s profits remain extremely low, said a manager surnamed Liao.

“We’ve got no other option. The goal now is to survive,” she said.

In sharp contrast with these types of private plights, strong cash flow and greater loan capacity have helped state-owned enterprises (SOEs) recover relatively faster this year after Beijing put an abrupt end to zero-Covid controls in December.

Few private company peers can make such big concessions, which means they can’t compete for orders from such big customers

Jason Liang, who manages a state-owned trading company in Guangdong, pointed to a recent deal that illustrates how state firms continue to have a leg up on their private counterparts.

“A very simple example – we are now able to send more than US$10 million worth of products to the warehouse of a big buyer [a supermarket chain] in Australia, where they sell the products first, and then we collect the final payment after 90 or 120 days,” Liang said. “Few private company peers can make such big concessions, which means they can’t compete for orders from such big customers.”

Already this month, Zheng Shanjie, director of the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), has held two discussions with private entrepreneurs to “listen to the real situation [of private companies] from various sides”, including different industries and regions.

And in response to specific appeals and suggestions raised by enterprises, China’s top economic planner has vowed to assess the current policies and unveil new supportive measures to help the private sector.

German firms’ hot take on China business belies Beijing’s charm offensive

Meanwhile, from industrial output to investment totals and revenue, a recovery in the private sector has been slower than at the state level.

For the first five months of this year, fixed-asset investment by private firms fell 0.1 per cent from the previous year, in sharp contrast with the rise of 8.4 per cent among their state-owned rivals.

Profits of private industrial enterprises with annual revenues of at least 20 million yuan fell 21.3 per cent to 683.8 billion yuan in the first five months of this year, compared with a drop of 17.7 per cent to 962.5 billion yuan by SOEs.

According to the latest data from the State Administration for Market Regulation, the number of registered private enterprises in China surpassed 50 million in early April and reached 50.9 million by the end of May – a 3.7-fold increase from 10.86 million at the end of 2012.

And private enterprises now account for 92.4 per cent of all companies in China, the official figures show.

Experts and analysts say that only increased fairness in access to resources and financing, with certain and stable policies, are likely to quell the current confidence crisis among private enterprises. And in the absence of such measures, some say China’s recovery outlook could be delayed.

“The lack of confidence in private capital has been an issue of great significance that may lead to systemic impacts,” said Liu Yuanchun, president of Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, in an interview with the Finance 40 Forum think tank in late June. “In particular, we should pay attention to the existence space for the private sector, its availability to funds and whether it can enjoy fair competition.

“We should also aim to help SMEs effectively obtain orders and reverse the worsening of profits and balance sheets.”

Even in the most promising private sectors, such as new energy, investors are not immune to the effects of policy uncertainties.

Earlier this year, Billy Wang leased a piece of land spanning nearly half a square kilometre in Guangdong province, to install centralised photovoltaic power panels.

So now Wang is at risk of losing his nearly 20-million-yuan investment if the project ends up being axed.

Lin Caiyi, vice-president of the China Chief Economist Forum Research Institute, said the lack of resources and confidence are behind the disparity in a post-pandemic recovery, and that support for the private sector should not be merely lip service.

China warned of ‘big’ debt risks in drive to narrow urban-rural gap

“The most important thing is to ensure the rule of law. At the beginning of China’s reform and opening up, policies were very stable, thus giving people strong confidence, which led to prosperity in the private sector. However, in recent years, private enterprises have seen great instability and unstable policies,” Lin said.

“Funds flying into SOEs, such as in property financing, have been much more than those to private firms,” she added. “The private sector is underprivileged in obtaining resources. Despite pledges to treat them equally and fair, concrete moves are still lacking.

“On the other hand, SOEs can rely on state support as a last resort in difficulties, while entrepreneurs have to take risks and bear losses all by themselves. Only once they are confident will they be willing to invest. Currently, however, the general expectations are quite unsettling.”

According to a Fitch report released in early May, steady new contract signings and a large backlog of orders in water resources management, hydropower, renewable energy, environmental protection and municipal development have helped ensure that state-owned engineering and construction companies are achieving above-industry-average growth rates in 2023.

That will lead to private peers ceding more market share to state-owned enterprises, Fitch expects.

Zhang Wenkui, a researcher with the Development Research Centre of the State Council, warned that this imbalance in recovery will affect China’s overall economic growth and potentially hinder the nation’s long-term modernisation plans.

He said in an interview with Thepaper.cn in late May that the prolonged delay of payments by local governments to private companies become more severe during the pandemic.

“In addition, endless inspections and rectification conducted by some local governments, which were random but compulsory, would harm basic rights and interests of private enterprises and individuals,” Zhang said.

Market-oriented reform based on the rule of law should be the very core of China’s efforts to build a business-friendly market environment, he said.

Amid disparities in the business recoveries, coupled with a beleaguered property market and weak export outlook, many private entrepreneurs are bracing for fierce competition in the second half of the year.

“2023 is the most difficult year since I started my business,” said Joe Li, who has run an underwear-manufacturing business in Guangdong for 25 years. “Competition in the second half of the year will be fiercer.”

How will China’s SMEs shape up amid troubling return of triangular debt?

Despite bouncing back with their best performance since the first quarter of 2021, more than one-third (37.6 per cent) of small firms still closed or suspended operations in the first quarter of 2023, according to a survey of more than 11,000 micro- and small businesses by the Centre for Enterprise Research at Peking University.

The survey findings, released in May, said more business owners were confronted with high costs and fierce competition, while calls were on the rise for supportive policies to reduce costs.

“We had been very optimistic at the beginning of this year, expecting sales to at least double last year,” said Jeff Jiao, a sales engineer of Shenzhen-based consumer robots company, “but … there was no any growth in sales in the first half of the year.”

Zeng Zhao, who runs a Shenzhen-based tech company developing educational software, said the current state of China’s economy also affects innovation, as small tech firms find it “very difficult” to acquire financing.

“Domestic demand is no longer an attractive selling point to lure investors,” he said. “Private enterprises do not have enough qualifications nor collateral for bank loans, and it is not easy to get a loan, so the capital ends up going to state-owned enterprises.”

In his Finance 40 Forum interview, Liu with the Shanghai-based university called for a “redefining of fiscal policy” to directly subsidise the private sector while further cutting taxes.

“We should have new channels to directly inject lifeblood and subsidises into private sectors, in addition to indirectly aiding them,” he said.

He also suggested that authorities should place more orders with the private sector in government procurements, and be more innovative in setting laws and regulations.

David Fang, who runs a business making and exporting baking tools in Yiwu, Zhejiang province, said his business operations have “turned out to be harder” despite a strong inflow of potential buyers to the city this year and a rise in orders.

“Competition is fiercer, while profits are falling,” Fang said.

Like China’s most dynamic market players, Fang is trying to do his homework while weathering the headwinds. This includes cutting jobs, prioritising innovation, shifting away from low-profitability products, and turning inward with an eye on the domestic market.

“It is a market worth billions of yuan, and it’s worth taking great effort to explore and expand,” Fang said.

Additional reporting by Beata Mo