13:35

Migrant workers who transformed China now struggling to survive

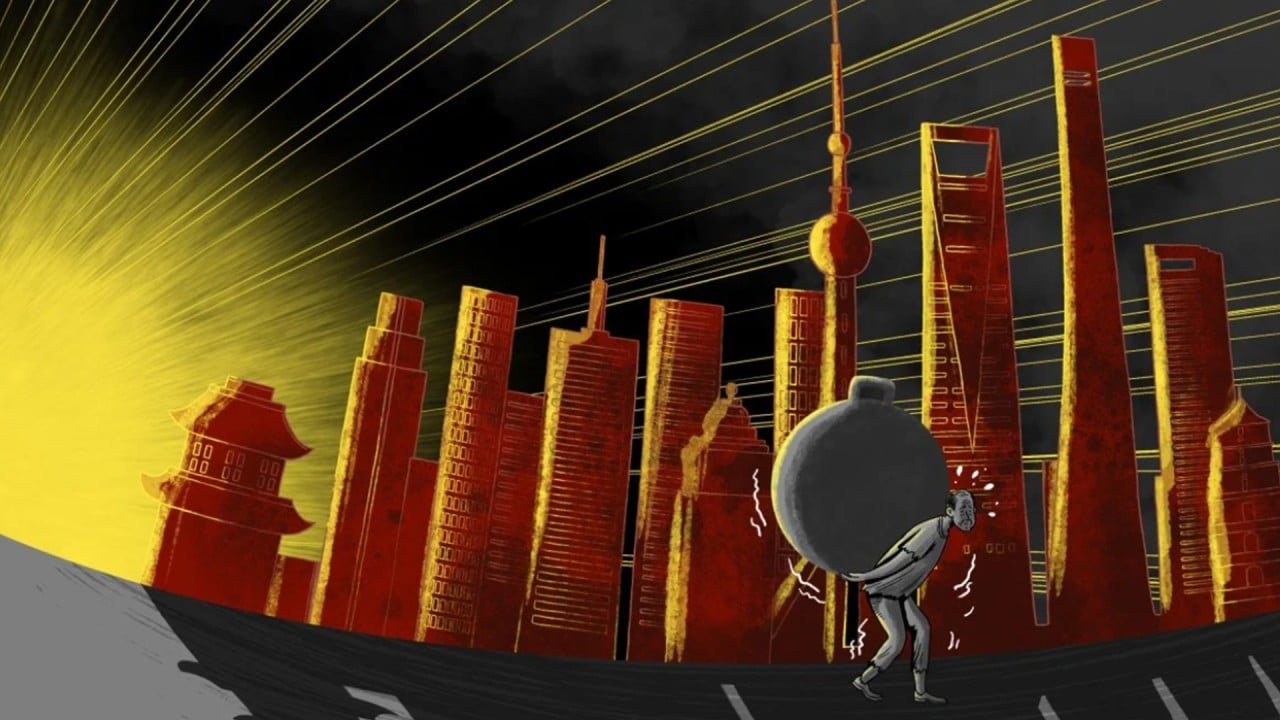

They made China’s economic dream a reality. Now, they struggle to survive

- Millions of migrants helped transform China from an agrarian economy into a manufacturing giant, but have yet to see major changes in their own living conditions

- Unequal distribution of benefits, precarious conditions mean most are working well past the statutory retirement age

When Geng Sheng stepped aboard a train bound for Shenzhen in 1982, it would have been impossible for him to imagine that he would take part in China’s economic transformation – the widest expansion of its kind in modern history.

But as their country has evolved into an economic powerhouse, many migrant workers like Geng are still waiting for the corresponding changes in their own lives.

Looking for a job in China

Geng, 68 and from a village in the central province of Hunan, now makes a living carrying light goods – and the occasional passenger – with an electric motorbike. He earns roughly 100 yuan (US$14) per day, which is enough to sustain his basic needs. He never married or received an education, so his expenses are low. But urgent medical bills threaten to push him into insolvency.

Geng’s story is not unique. Hundreds of millions flocked to coastal factories after former leader Deng Xiaoping opened up the country to foreign investors in 1979 and set up four special economic zones – Shenzhen, Zhuhai and Shantou in Guangdong province, and Xiamen in the neighbouring province of Fujian.

Low-cost Chinese products were shipped worldwide as masses of labourers worked hard to turn the nation from an underdeveloped agrarian state into a manufacturing centre dubbed “the world’s factory”.

This grew China’s economy at breakneck speed and lifted a record number of people out of poverty. In 2009, in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, “The Chinese Worker” was named by Time magazine as a runner-up candidate for its Person of the Year for helping shield their country from the worst effects of the meltdown and buoy the world’s economic recovery.

There have been plenty of success stories. Some migrant workers became entrepreneurs or lawmakers. A great deal were able to find their footing, either in their adopted homes or after making a return to their villages, as policies provided them with access to some public services and welfare.

More rich Chinese look to donate amid Xi’s ‘common prosperity’ call: survey

China has 290 million migrant workers according to the National Bureau of Statistics, including 86.33 million over 50.

A study released in June by Qiu Fengxian, an associate professor at Anhui Normal University, tracked the condition of first-generation migrant workers by sending out 2,500 questionnaires and interviewing 200 people.

About 60.7 per cent of older workers said they will “work until their physical health fails them” owing to the lack of stable pensions, and 76.1 per cent said they have worked past 60, or are currently.

As most of these workers are engaged in heavy physical labour or work in highly polluted areas, their health is generally poor and chronic injuries are common.

Geng himself suffered one such injury after an accident in 2002 damaged his leg and rendered him partially disabled. That, along with a lack of education, limited his opportunities and trapped him in lower-earning jobs.

Despite these hardships, he has become used to life in Shenzhen and is reluctant to go back to his rural home where he would be eligible for welfare, meagre though it would be. But employment prospects are bleak.

China’s migrants return earlier to major cities but find fewer jobs, less pay

“Since the easing of the pandemic, all the rural young people are seeking jobs in Shenzhen this year,” he said. “None of the factories want old workers like us.”

Pay differentials have also become more asymmetric. Per Qiu’s survey, from 1993 to 2005 the monthly wages of urban workers nationwide increased by 1,260 yuan, while the increase for migrant workers was only 68.

The study showed many first-generation migrant workers had less than 50,000 yuan of savings after working for 30 years. Societal expectations mean parents are forced to provide for their children well into adulthood, even going so far as to buy their houses. With these traditions, and a system which distributes the lion’s share of benefits to those with urban residency, this generation has been left out in the cold.

In China, social benefits are based on the hukou, an identity registration system that delegates access to education, healthcare and pension services.

For small illnesses we take medicine, for major illnesses we can only wait for death

Benefits for rural and urban registrants differ greatly. Urban workers often have a monthly pension of several thousand, depending on their region of residence and previous contributions, but the rural elderly only receive around 100 yuan per month.

Seventy-year-old Yan, who was reluctant to give his full name, is still working as a security guard in Zhengzhou, Henan province. He took the position to help his son, who lost his job during the pandemic but has a 1 million yuan (US$136,775) mortgage left to pay.

The job pays 2,000 yuan a month, far more than he could earn by tilting his plot of farmland, and Yan plans to continue working until his physical condition no longer allows it. Without city medical insurance, all he can hope for is not to get sick.

“We don’t receive a pension of several thousand yuan a month like city residents,” he said. “For small illnesses we take medicine, for major illnesses we can only wait for death.”

‘Factory jobs can’t teach you anything’: China’s migrants seek pastures new

In 2022, the number of people covered by basic pension insurance – where the rural population is most of payroll – was 549 million, and the fund’s expenditure was 404.4 billion yuan (US$56.15 billion), according to the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security.

Over 503 million people were insured in the basic pension insurance for urban workers, with expenditures of 5.9 trillion yuan (US$819.25 billion) – nearly 15 times as much as rural pensions.

First-generation migrant workers are mostly urban wanderers who do not have stable jobs or labour contracts. As such, they rarely have fixed pension accounts and consequently lose a number of benefits, said Zhao Xijun, a finance professor at Beijing-based Renmin University.

Susanne Choi, a professor of sociology at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, said rural migrant workers in some cities still receive different treatment, despite promises to widen access to local welfare through a points-based system.

“[It is unclear] whether these proposals will be accepted, and how they would be implemented,” Choi added. “And even if implemented, their impact on the lives of migrant workers is uncertain.”

Times are tough even for those who manage to get a job. Of the elderly migrant workers who were employed, Qiu’s survey shows one-fifth did not actually receive their promised salary.

Late pay and demanding work drives delivery worker protests in China

With little recourse, they tend to turn to friends or relatives for help. Around 13.5 per cent just give up.

“We migrant workers can only accept our fate when we are owed wages,” said Duan, a widower selling food on the street of Shenzhen.

Originally from northeast China’s Heilongjiang province, Duan did a variety of part-time jobs across the country over the past three decades, but none of them carried benefits that could help him contribute to social security and settle down.

“My last factory job was before the pandemic,” he said. “Many factories shut down during Covid. I had zero income in 2022.”

Duan has been struggling to pay social security as a flexible worker, and would need to pay in for another 100 months to qualify for a government pension.

“I don’t think I’ll live to see that,” he said.

But the pandemic and the strict zero-Covid policy that followed have hampered those efforts. After numerous businesses were forced to shut down, many of these first-generation migrant workers are right back where they started.

Edwin Lai, a professor of economics at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, said China has made historic achievements in reducing poverty, but the misery of migrant workers has exposed a weak spot in Beijing’s ambitious plans.

Has one philosophy student changed the face of migrant workers in China?

Progress in the push for greater equality must be made carefully, however, as rigid enforcement of the policy “does not just scare away the private sector, but also erodes [their] confidence,” he said.

Chen Zhiwu, chair professor of finance at the University of Hong Kong, said China currently lacks an information channel through which the central government can directly understand the living conditions of poor people, making it difficult for Beijing to judge the progress of poverty reduction efforts.

In addition, China still has enough fiscal room to improve basic protection for migrant workers and increase financial support, while a more transparent mechanism is needed for citizens to monitor the use of poverty elimination money, Chen added.

“[Without] institutional infrastructure to ensure that every dollar spent by the government is actually done in accordance with the common prosperity principle, the results we see are not surprising,” Chen said. “They need to let these migrant workers make their voices heard.”