China, South Korea battle population woes as ‘children are not a must’, adding to economic peril

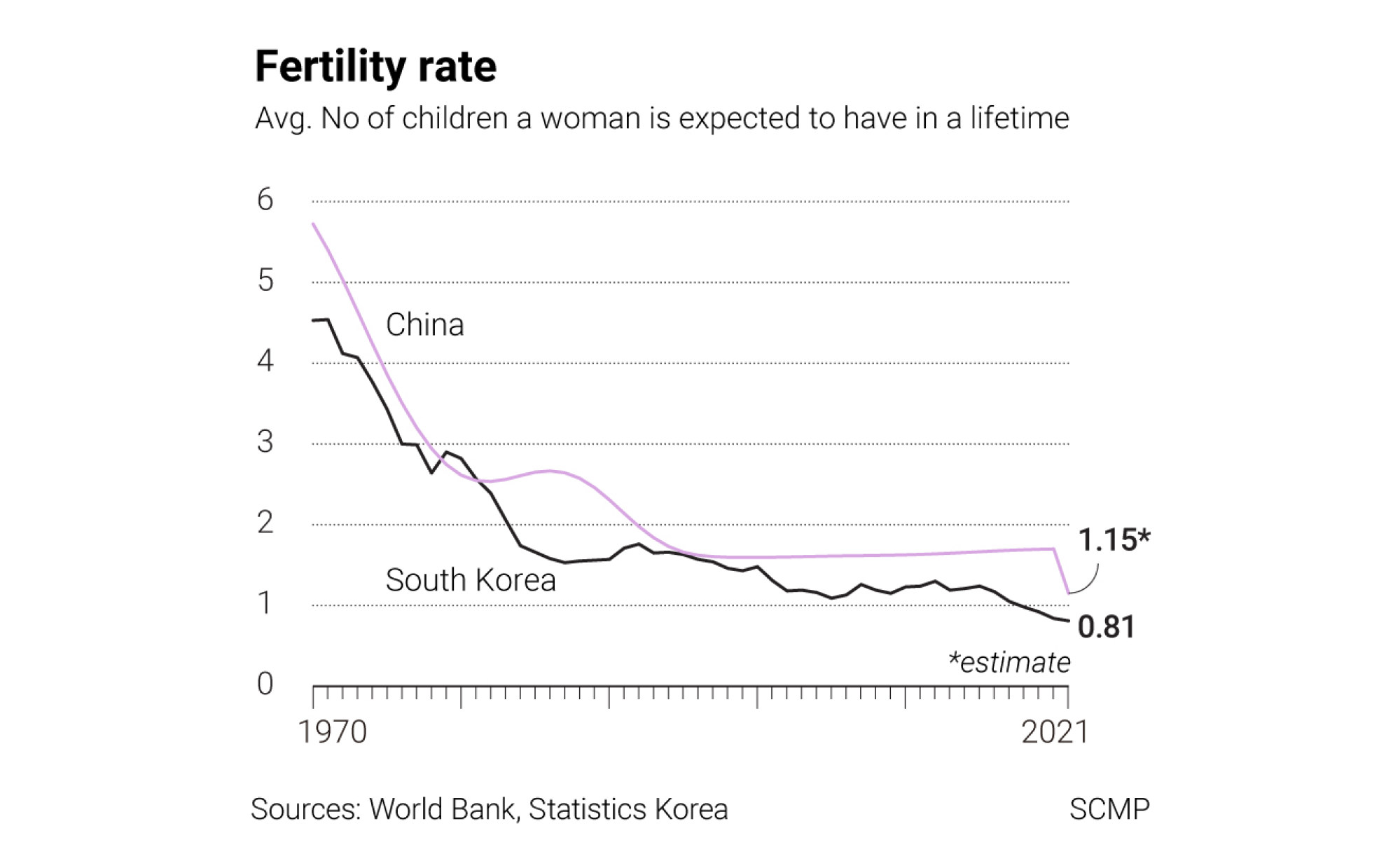

- South Korea’s fertility rate fell to a record low of 0.81 last year, increasing the pressures faced by its economy due to an already rapidly ageing population

- China’s fertility rate is estimated to have fallen to 1.15 in 2021, also adding to its problems of a tumbling number of births and an ageing population

Japan has long been the poster boy for population crisis, but South Korea’s fertility rate is now one of the lowest in the world, and China’s is not much better.

Last year, in a nation of over 51 million people, the average number of children a woman in South Korea was expected to give birth to in her lifetime sat at 0.81 – the lowest since Statistics Korea began compiling related data in 1970 when the figure stood at 4.53 and down from over 2 in 1983.

Economies faced with an ageing population are paying close attention to fertility rates as they reflect a trend that enables governments to make projections for longer-term changes in population.

My husband says having children will limit life choices

Lower fertility rates are expected in developed countries due to things like wealth, education and urbanisation, while the figure in undeveloped countries tends to be higher as families seek labour to earn money and carers for their parents in old age.

In stark contrast to South Korea and China, the landlocked country of Niger in North Africa – which is one of the least developed countries in the world – had one of the highest fertility rates last year with an average of close to 7.

“My husband says having children will limit life choices. For me, there are a number of factors, such as uncertainty about whether my child will have a happy future considering the deteriorating natural and social environment, but also because it will be difficult to continue working with a child,” said married 34-year-old South Korean interior designer Han Jia.

“Korea has improved its childcare leave system, and men are becoming more involved in the household, but there is still a long way to go.”

South Korea’s rapidly ageing population, driven by an increasing reluctance to have children as well as longer life expectancy, is putting the country’s economy in peril.

South Korea became an aged society in 2017, with more than 14 per cent of the population 65 and older, having become an ageing society in 1999, when more than 7 per cent of the population fell within the bracket.

The figure is projected to reach 37 per cent in 2045, which will make South Korea one of the oldest populations in the world.

Life expectancy at birth in South Korea also stood at 83.5 years in 2020, before the population started contracting for the first time the following year amid a falling birth rate.

This poses structural problems for the economy, as a smaller, aged population indicates a shrinking labour force and faltering domestic demand.

In Japan, concerns over its fertility rate started in the late 1980s. It eventually hit a low of 1.26 in 2005, and after marginally recovering to 1.45 in 2015, has slid for the last six years to 1.3 last year.

There were 811,604 births in Japan last year, the fewest since record began in 1899, while deaths climbed to 1,439,809, leading to an overall population drop of 628,205 to 125 million.

With also one of the fastest ageing populations in the world, the productivity from China’s vast labour force is also projected to fall as well.

Children are not a must-have in my life and I don’t have the confidence yet

“Children are not a must-have in my life and I don’t have the confidence yet. Because raising children is a complicated challenge – economically speaking, it’s a very costly process,” said Felizia Yao, a 27-year-old single woman based in Shanghai.

“With my current financial situation, the burden of raising a child will mean sacrificing my own quality of life. So currently, I don’t have a reason to have a child.”

“In East Asian culture, childbirth means more dedication and sacrifice from women, while men are less involved in childcare,” He said.

“Married women who have children are vulnerable to discrimination in the job market. Many women are forced to choose to have fewer or no children in order to achieve career advancement.”

Is a demographic turning point just around the corner for China?

Women in the region are “now more aware of gender inequalities”, said Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs research fellow Lee Sang-lim, with a social system that lags in facilitating childcare meaning that women are increasingly opting not to get married and give birth.

“It is difficult to even maintain my career with one child,” said 39-year-old medical professional Kim, who only wished to be identified by her surname. She is already raising a three-year-old daughter in South Korea’s capital of Seoul.

“Women are expected to play a key role in children’s upbringing, but where I work, women are also expected to deliver the same performance workwise.”

I did not entirely rule out having a second child, but after I took on the part-time job, I realised that it has become even more difficult to have another child

Lee Joo-yeon, 34, has been unable to return to a full-time office job after giving birth to her now four-year-old son and she finds herself working part-time at a shop in Pyeongtaek in Gyeonggi province.

“I did not entirely rule out having a second child, but after I took on the part-time job, I realised that it has become even more difficult to have another child, because I am tired after coming home from work but still need to take care of my son,” said Lee Joo-yeon, who initially stopped working after she got married as she moved to a different city.

Yuan Xin, vice-president of the China Population Association and a demography professor at Nankai University in Tianjin, said Confucian culture is behind the low fertility phenomenon of the region.

“Countries in the East Asian cultural sphere are known for sparing no effort for their children’s education,” he said, referring to the ancient Chinese belief system, which focuses on the importance of personal ethics and morality.

“The cost of raising a child, whether it’s a direct cost or an indirect cost, is very high compared to developed countries in the West, especially the indirect cost – which is the cost of time and care other than money, such as the time parents and families spend on cultivating the children, including tutoring.”

‘To have more children, we are asking Chinese women to get married early’

South Korea and China also face similar fundamental problems that are deterring people from having children – a tough job market and expensive housing costs.

“The shortage of stable jobs and subsequent difficulty young people face in the job market, high housing prices and expensive private education costs are behind the phenomenon,” research fellow Lee Sang-lim added.

Demographer He pointed out that the social stigma that conservative societies in East Asia impose on “unmarried mothers and illegitimate children” has resulted in a comparatively low proportion of children born out of wedlock.

He noted that in some developed countries in Europe, as well as the United States, the traditional model of marriage and childbirth is no longer the absolute mainstream.

“There are many economically independent women in these countries who do not want to be bound by marriage, but want to have their own children,” he added.

“In recent years, the proportion of children born out of wedlock in France and the Nordic countries has exceeded half of all births.”

South Korea’s falling number of marriages is also contributing to the declining birth rate, with the figure having continued to fall over the past decade with only 192,500 taking place last year compared to 327,100 in 2012.

Last year, South Korea saw a 4.3 per cent drop in births from the previous year – with mothers giving birth to just 260,500 babies, with a birth rate of 7.036.

This added up to a population decline from 51.84 million in 2020 to 51.75 million – a decrease of 0.18 per cent.

Having children will seriously limit my own future potential

“Having children will seriously limit my own future potential,” said Spike Jin, a 24-year-old Chinese man working in the blockchain industry.

“The financial burden [of having children] is part of the limitation, of course. Having more money means I have more options, namely more potential. Once you have a child, it would be much harder to refuse societal norms imposed on you. When you’re alone, you could justly do whatever you want without burdens.”

A growing portion of younger people also now value personal achievement and freedom over the traditional path of getting married and having children.

“I need time for myself to achieve my goals and fulfil myself first before raising a kid,” said Reona Ding, a 33-year-old married woman in China.

The reluctance of its younger generation to have children will prove to be a core challenge for China after its natural population growth rate fell to 0.034 per cent last year, which was the lowest since the great famine from 1959-61.

Last year, China saw an 11.5 per cent drop in births – with mothers giving birth to just 10.62 million babies, contributing to an overall population increase of just 480,000.

“A higher income may lead to a shift to spending more on self-development and pleasure, from spending on family and children,” the China Population Association’s Yuan added.

South Korea is the only country with a fertility rate of below 1 per cent among the 38 member states of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, which includes Japan and South Korea but not China.

The total fertility rate for the first quarter of 2022 rose to 0.86, but was still the lowest first quarter figure on record.

The government has dealt with the low fertility rate as a separate issue, instead of addressing it with an integrated policy approach

It had begun devising policies decades earlier to tackle the demographic changes, with attention focused on facilitating and expanding parental childcare leave, increasing day care centres and childcare services and providing allowances for child birth and childcare.

But these have evidently proven to be ineffective, given they do not accompany effectively addressing more fundamental problems such as the tough job market, skyrocketing housing prices and high costs of raising children.

“The policies have not offered support to the extent that these cancel the effects of the increasing burden of housing or private education costs,” Lee Sang-lim said.

“The government has dealt with the low fertility rate as a separate issue, instead of addressing it with an integrated policy approach. There needs to be efforts to tackle the issue with a macro-perspective.”

China’s three-child policy: why was it introduced and what does it mean?

Central and local governments in China have also been stepping up efforts to encourage the young generation to have children by expanding paternity leave and introducing tax benefits.

But experts agree that the measures need to go beyond monetary incentives to address fundamental reasons that hinder child birth.

“To increase the fertility rate, it is necessary to eliminate gender discrimination in the job market and ensure women’s right to fair employment,” demographer He said.

“The second is to appropriately shorten working hours. Working hours in East Asian countries are too long. The long working hours have affected the people’s willingness to have children in these countries to a certain extent.”