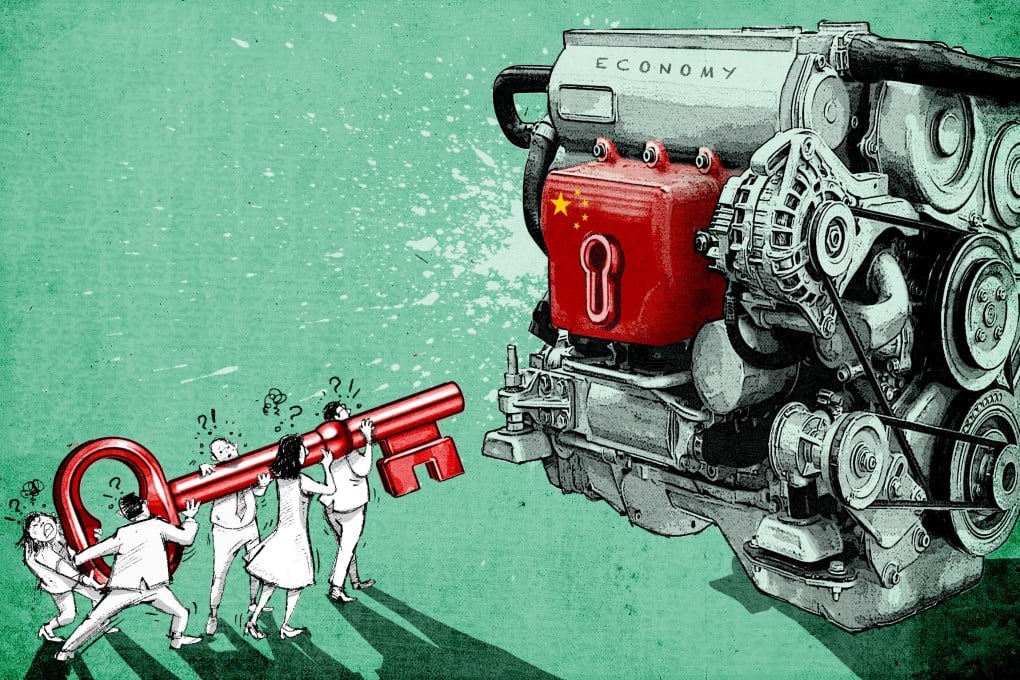

From consumption to tourism, China’s middle class holds the key to revving up economic engine, but can they turn it?

- Ahead of China’s quarterly GDP release, survey figures reflect how difficult times have been for half a billion Chinese people, and where their priorities now lie

- Even economic bright spots such as EV manufacturing have cast a long shadow of uncertainty, shrouding an outlook already marred by property and spending woes

First they came for Zibo’s barbecues. Then they returned in droves for the stunning ice sculptures of Harbin. After that, numbing noodles put Tianshui’s hotpot on their radar and palates.

Now Chinese tourists are flocking to Chengdu to catch a glimpse of cherry blossoms and rapeseed flowers in full bloom.

How much those efforts have been paying off remains to be seen, but some insight should come from China’s expected release of its quarterly gross domestic product (GDP) on Tuesday. And data on retail sales and property investment may offer additional clues into whether consumer confidence has shown signs of recovery.

Since last year, Beijing has stepped up measures to boost spending in the automobile, real estate and tourism industries as leadership tries to fuel an economy that has sputtered since the pandemic.