Explainer | US-China relations: is there still a trade war under Joe Biden’s presidency?

- Former US president Donald Trump instigated the trade war with China in July 2018, and their phase-one trade deal was eventually signed in January 2020

- Joe Biden took over the presidency at the start of 2021, saying his administration would review the trade war and other actions taken against China

How did the trade war start?

During his 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump promised to reduce the trade deficit with China. He claimed it was based in large part on unfair Chinese trading practices, including intellectual property theft, forced technology transfers, a lack of market access for American companies in China, and an uneven playing field caused by Beijing’s subsidies for favoured Chinese companies.

China, meanwhile, believed that the United States was trying to restrict its rise as a global economic power.

The US and China are the two largest economies in the world, and Chinese foreign trade grew rapidly after its ascension to the World Trade Organization in 2001, with bilateral trade between the US and China totalling almost US$559 billion in 2019.

When did the US-China trade war start?

At its peak at the end of 2019, the US had imposed tariffs on more than US$360 billion worth of Chinese goods, while China had retaliated with import duties of its own worth around US$110 billion on US products.

What is the phase-one trade deal?

Trump and China’s chief negotiator, Vice-Premier Liu He, signed the agreement at the White House. As part of the deal, China agreed to buy an additional US$200 billion worth of American goods and services over the following two years, compared with 2017 levels.

Those additional purchases would be made up of around US$77 billion in manufacturing, US$52 billion in energy, US$32 billion in agricultural goods and US$38 billion in services. The latter includes tourism, financial services and cloud services.

China also pledged to remove barriers to a long list of US exports, including beef, pork, poultry, seafood, dairy, rice, infant formula, animal feed and biotechnology, according to Trump.

The deal also resulted in the US suspending a planned 15 per cent tariff on around US$162 billion of Chinese goods, with an existing 15 per cent duty on imports worth around US$110 billion halved to 7.5 per cent. China also suspended retaliatory tariffs.

What is the status of the phase-one trade deal?

The report said China’s imports of goods covered by the phase-one deal were 13 per cent higher in 2020 than in 2019, although this was partly the result of a low base from one year earlier, due to China’s retaliatory trade war tariffs on US goods.

China’s purchases of manufacturing goods covered under the deal met just 57 per cent of the target in 2020, with cars, trucks and parts meeting just 40 per cent of the target, while aircraft, engines and parts met just 18 per cent of the target.

Semiconductors and semiconductor manufacturing equipment, though, exceeded the target by 27 per cent, although the report said this was due to Chinese buyers, including Huawei Technologies Co., stockpiling supplies in anticipation of the US restricting exports of certain products on national security grounds.

Sales of medical products to China also hit 111 per cent of the target due to demand caused by the coronavirus pandemic.

Agricultural exports fell 18 per cent short of the target in 2020. Significant purchases of goods such as pork, corn, cotton and wheat helped, but declines in soybeans and lobsters dragged the figure down. Also as part of the deal, China lifted import restrictions on a raft of American farm goods, including poultry, pork, soybeans and barley.

China’s imports of energy products met just 37 per cent of the commitment, the report said. Liquefied natural gas hit 89 per cent of the target, but coal hit just 14 per cent and crude oil 45 per cent. This may have been in part due to historically low oil prices over much of 2020.

How will a Joe Biden presidency impact the US-China trade war?

In an interview with The New York Times published at the start of December 2020, Biden said the “best China strategy” was to get all traditional US allies in Asia and Europe “on the same page”, which will be his major priority “in the opening weeks” of his presidency.

Biden said his trade policies would focus on “China’s abusive practices”, including “stealing intellectual property, dumping products, illegal subsidies to corporations” and forced technology transfers.

04:07

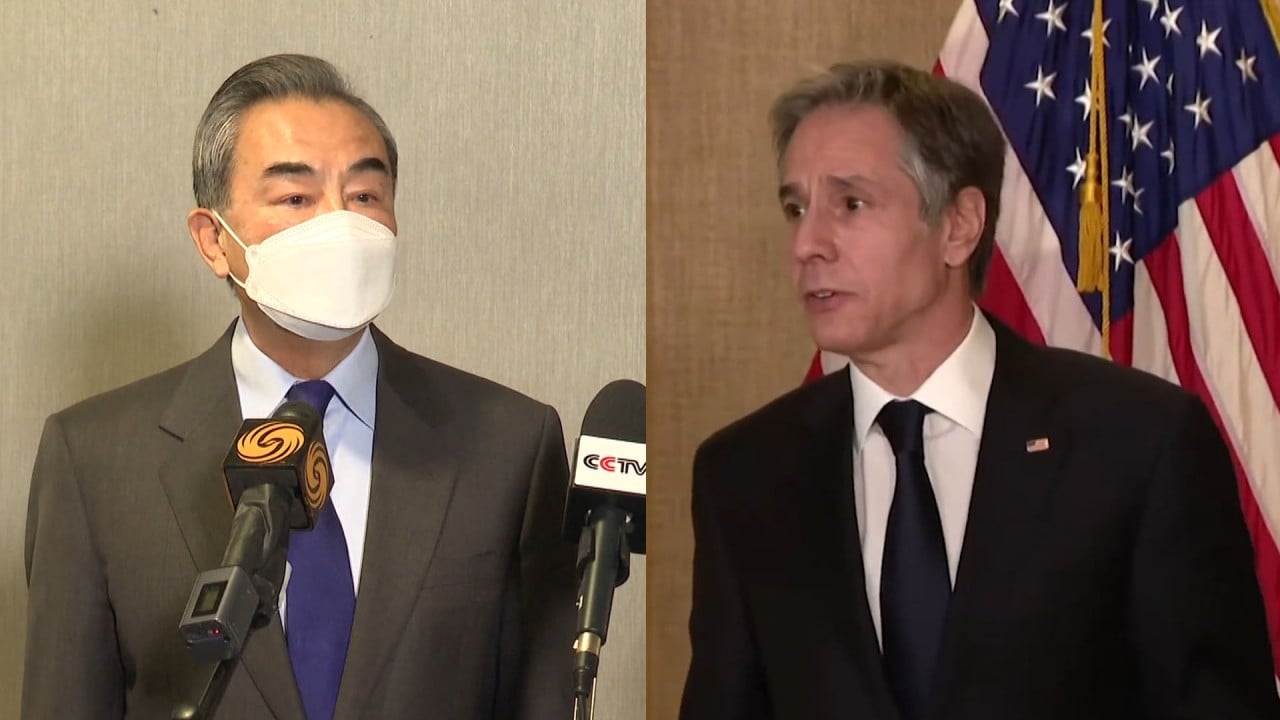

Alaska summit: China tells US not to underestimate Beijing’s will to safeguard national dignity

A “top-to-bottom review” of China’s trade policy by the Biden administration is set to include how to approach Trump’s phase-one trade deal with Beijing that expires at the end of 2021.

A statement from the USTR’s office said that Tai had discussed the guiding principles of the Biden administration’s worker-centred trade policy and her ongoing review of the US-China trade relationship, while also raising issues of concern.

The statement was issued by Tai, US Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo and European Commission executive vice-president Valdis Dombrovskis.

What is the ‘targeted tariff-exclusion process’?

This marked Tai’s first public statement since assuming her role at USTR on a significant policy area, but she did not share much information on what US-China trade policy will look like over the coming year and did not signal a shift in the overall trade policy towards China.

US stakeholders are typically permitted to petition for an exclusion if punitive tariffs placed on foreign products cause domestic commercial harm. Since former president Trump slapped tariffs on imports of Chinese goods, companies have been filing requests to exclude certain Chinese products from punitive tariffs. Although there are three criteria for such an exemption, the process has come under scrutiny for not being transparent enough.

Want to know more about the US-China trade war?

.JPG?itok=J8tgfPmW&v=1659948715)