China ‘supplementing’ South Korean industrial development model as tech sectors catch up

- Trade between China and South Korea previously operated on a win-win basis as displays and semiconductors flowed across the Yellow Sea

- Competition has intensified in the chemical, general machinery, automobiles, electricity and machinery industries sectors within the middle and hi-tech industries

As China’s industrial structure is advancing and catching up to South Korea, many have been pointing out that relations between the two Asian heavyweights are gradually transforming from being complementary to competitive.

But in recent years the two countries have begun to compete in middle and hi-tech industries, with the once complementary dynamic now on the decline and China’s hi-tech industry becoming increasingly important.

According to the Institute for International Trade at the Korea International Trade Association, competition has intensified in the chemical, general machinery, automobiles, electricity and machinery sectors within the middle and hi-tech industries.

In terms of cutting-edge technology industries, competition has intensified in aerospace and medical and precision optical equipment, the research showed.

China is seen to be going through a similar industrial structure progression that South Korea went through, although it is not following the exact footsteps in terms of industrial policies, economic experts from both countries said.

It is instead “supplementing parts that are lacking in the Korean developmental model” and “benchmarking various countries’ successes and failures”, said Kim Kyung-hwan, a China analyst at Hana Securities.

China’s industrial upgrading process before 2010 was very similar to that of Korea between the 70s and 90s, which was represented by the development of heavy industries

“China’s industrial upgrading process before 2010 was very similar to that of Korea between the 70s and 90s, which was represented by the development of heavy industries – such as large-scale automobile, shipbuilding, semiconductor, etc based on export manufacturing – and the state-led growth process,” Kim added.

Zhang Monan, the deputy director of the Institute of American and European Studies at the China Centre for International Economic Exchanges, said that Seoul’s policies played a major role in developing various industries in South Korea.

“South Korea has implemented many industrial policies, especially in industries such as steel, petrochemical, shipbuilding, automobile, semiconductors and electronics, aerospace and culture, and the government has made great efforts to promote it,” Zhang said.

The big conglomerate companies in South Korea – referred to as chaebol in Korean – greatly expanded in the 1970s, in part benefiting from the Korean government’s industrial policies that sought to transition from labour-intensive light industry to heavy and chemical industries.

The chaebol, which include the likes of Samsung, Hyundai, LG and SK, still play an oversized role in driving the Korean economy, with their combined assets accounting for nearly half of the country’s gross domestic product, while they are also very successful internationally.

In 2021, Samsung was the leader in semiconductor sales worldwide, accounting for 12.3 per cent of the total market with US$73.1 billion, according to American technological research and consulting firm Gartner.

The shipbuilding industry in South Korea is very strong as well, ranking second worldwide in 2021 in terms of total global orders and ranking first in terms of high value-added and eco-friendly ships.

“China and South Korea have different national conditions and cannot fully learn from relevant experiences. [However, one lesson] is that industrial policy must be matched with the market and other macroeconomic policies,” Zhang added.

“It is necessary for the government to optimise the allocation of resources through industrial policies.”

South Korean economists said that although government policies did play an important role, there were many other elements that were vital. These included the entrepreneurship of private companies, human capital, competitive industrial structure and the tendency of enterprises to not only have the domestic market in mind.

“When you look especially at the case of Samsung and its most representative product semiconductors, there was very strong dissent within the company initially when it started nurturing semiconductor production, because many thought it was such a dangerous big scale investment,” said Lee Doo-won.

“So semiconductors was really not an industry that developed in Korea because of governmental support, but was rather something that Samsung’s [founder] Lee Byung-chul and [former chairman] Lee Kun-hee bore all the risk for. There really is a limit to nurturing an industry purely based on full governmental support”

Kim added that while the past Korean administrations generally fostered a policy environment that was friendly to conglomerates, it has not really been the case in the past five to 10 years.

There has also been a question mark in recent years when it comes to whether there is a good environment for such entrepreneurial spirits to flourish, Lee Doo-won added.

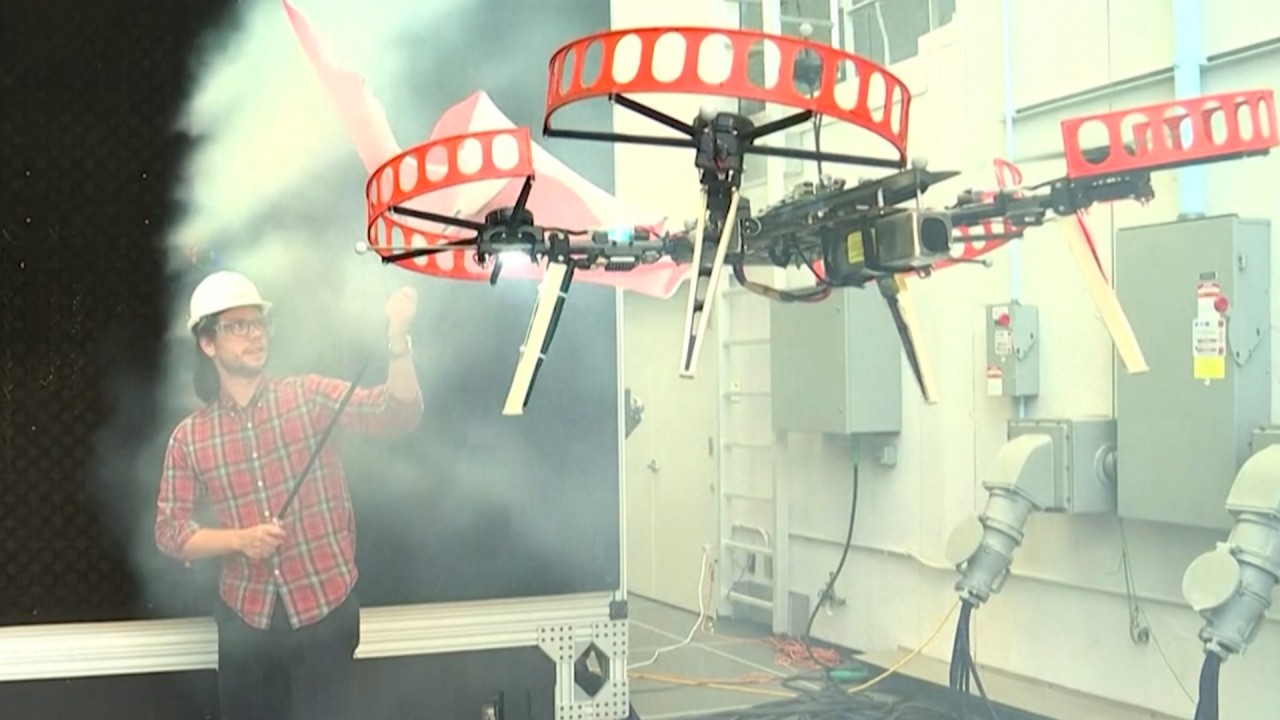

The Chinese government seems to be more enthusiastic about nurturing new industries, such as solar power, drones, AI, and electric vehicles, than the Korean government.

“There are a lot of concerns within Korea that new enterprises cannot take off, especially in the service and new industries, if the government keeps regulating private companies. One recent example is Tada, a car sharing service that shut down business because of government regulations,” Lee Doo-won said.

“In this regard, the Chinese government seems to be more enthusiastic about nurturing new industries, such as solar power, drones, AI, and electric vehicles, than the Korean government.”

DJI, the biggest drone manufacturer in the world from China, took up 76 per cent of the global market share in 2021 with sales volume estimated to be up to US$3 billion.

South Korea, on the other hand, is a latecomer to the industry and insiders predict that the domestic drone market will grow up to US$589 million by 2024.

Another sign of China’s push for developing new industries is its research and development spending, which grew by an average of 14.8 per cent annually from 2010 to 2016, far exceeding the global average, according to Zhang.

In fact, China’s R&D investment in 2020 increased by almost fourfold compared to 2000, and the number of international patent applications in China surged from 276 in 1999 to 58,990 in 2019, achieving a rapid development of nearly 200 times in 20 years.

China’s industrial advancement model – as it has upgraded its industry from mid-low end to the mid-high end and also developed its hi-tech manufacturing industry – is still seen to be similar to that of South Korea in that there were strong government industrial policies supported by good human capital, and flourishing domestic competition.

Lee Doo-won, though, pointed out some of the differences between the two development models, including an environment in China that is less conducive to entrepreneurship of private companies.

Stronger governmental control, zero-Covid policies, regulatory crackdowns and the tightening of political control are some of the factors often cited as hurting entrepreneurial spirit and the dynamism of the private sector.

In the past decade, China has also been implementing its unique industrial development model that the government seems to have devised from taking reference from other countries’ various plans.

In the past three years, it seems like the Chinese government’s industrial policy has changed to the German, Korean, Singaporean and Taiwanese-style model

“In the past three years, it seems like the Chinese government’s industrial policy has changed to the German, Korean, Singaporean and Taiwanese-style model, where the proportion of the manufacturing industry is kept high, while creating employment, income and added value,” Kim said.

“It seems like there will be various attempts to adjust to new crises – such as the current omnidirectional American regulation in the technology sector, retreat of globalisation, supply chain dispersion and the energy crisis – instead of simply following the Korean advancement model.

“I believe there are not many areas that China can emulate the Korean development model other than in special fields such as hardware, semiconductors and shipbuilding.”

Zhang added that another important lesson Beijing could learn from the Korean model is the importance of giving the market its full competition.

“With the continuous development of the industry, the government should gradually reduce its direct intervention in the development of the industry and instead create a better environment,” Zhang said.