China, Australia ‘natural partners’, ex-diplomat says, but are ‘rebalancing the equation’ after 50 years

- Career diplomat David Ambrose, who took his first diplomatic posting to Beijing in 1975, believes that China and Australia should seek to ‘build on’ their relationship

- President Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Anthony Albanese met last month, just ahead of the 50th anniversary of diplomatic and trade ties between the ‘natural partners’

As China and Australia enter the 50th year of diplomatic and trade ties, both of which have been strained in recent years, a former Australian diplomat believes the most important quality in sustaining mutual understanding and trust is “objectivity” at a time of a “rebalancing of the equation”.

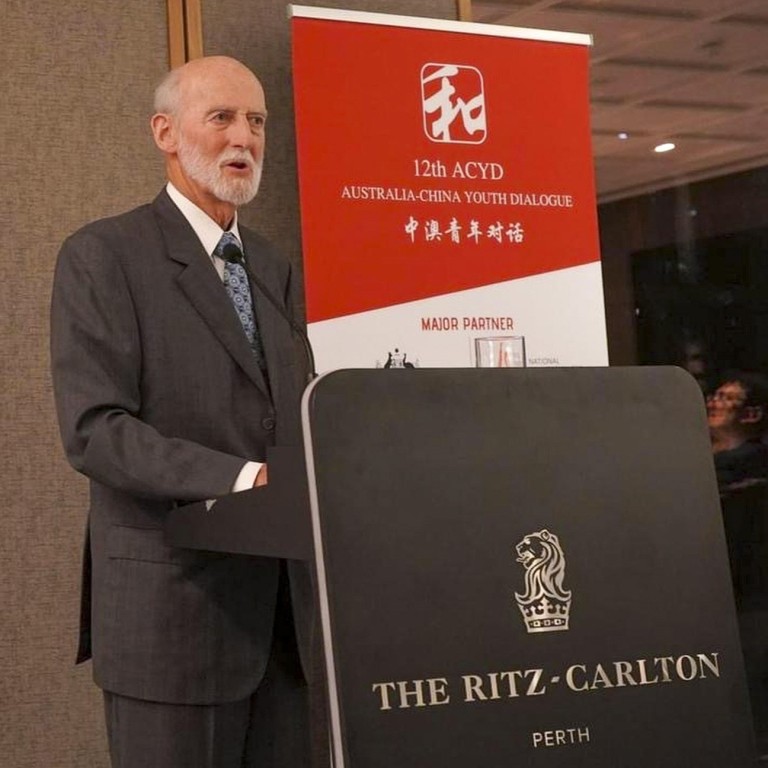

Career diplomat David Ambrose, who took his first diplomatic posting to Beijing in 1975, believes that China and Australia are “natural partners” with complementary economies and no natural conflicts of interest, while both should seek to “build on” their relationship instead of just “restoring” ties.

Ambrose cited the projection from the Australian government, which forecast that China’s contribution to global gross domestic product (GDP) as a percentage of global output by 2035 will be at 25 per cent, compared to 14 per cent for the United States.

[Being objective] means at least detaching yourself from both your own interests and your own biases sufficiently

“[Being objective] means at least detaching yourself from both your own interests and your own biases sufficiently to actually look at the other side and try to understand its positions,” Ambrose explained in an interview with the Post on the sidelines of the 12th Australia-China Youth Dialogue in Perth at the end of last month.

“My own view for a very long time has been that the Americans cannot be objective about China because it’s communist, and they have a visceral dislike and distrust of communism.”

According to Ambrose, an unrecognised influence that can damage the development of a relationship is ideology, which he added that it “in a sense distorts the way you look at your so-called opponents”, because sticking to certain beliefs will influence policy and will lack objectivity.

Ambrose, who has also served in Hong Kong, Belgrade, Vanuatu and Shanghai, believes that trust plays a big role in maintaining an amicable bilateral relationship, but the relationship has now suffered a “a breach of faith” that needs to be rebuilt.

“The Chinese are not going to drive the Americans out of the Western Pacific,” he said.

“But there has been a shift in preponderant wealth and power and one that confronts Australia with choices.”

China is, Ambrose added, “a huge part of national incomes”, pointing to iron ore and liquefied natural gas, which comprise the largest part of Australia’s exports.

After 2.5 years of tension, China and Australia’s relationship seeks new energy

Official figures up to October from the Government of Western Australia’s Department of Jobs, Tourism, Science and Innovation showed that the mining industry accounted for nearly 50 per cent of the state’s GDP in 2020 and 2021.

Western Australia, as Australia’s largest state, also contributed 17.5 per cent of the overall national GDP.

In terms of helping China get on the path of successful modernisation, however, Ambrose believes that the US has probably done more than any other country through foreign investment, technology transfer and academic exchanges over the past decades.

“It’s a problem now of the US having codified its ideology and characterised the whole relationship with China as a clash between ideologies – democracy and the rule of law against autocracy,” added Ambrose, the one-time supervisor of former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd and current Australian ambassador to China Graham Fletcher

“There’s a kind of arrogant assumption that China would transform itself progressively to look more like us.”

Ambrose was appointed as national assessments officer responsible for the communist Asia, including North Korea, China, Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos for the Office of National Assessments, which was set up by then-prime minister Malcolm Fraser in 1977 to provide intelligence on political, strategic and economic issues.

China and Australia had only established diplomatic relations five years earlier when Gough Whitlam was elected as Australian prime minister in 1972.

The two countries enjoyed their “sunshine years” between the 1980s and 2000s, according to Ambrose, as China’s steel industry took off due to its economic development.

In 1984, with Ambrose now head of the China section at the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, then-premier Zhao Ziyang agreed with then-Australian prime minister Bob Hawke for Chinese investment in the Mount Channar joint venture iron ore mine located in the Pilbara region of Western Australia.

China and Australia signed the US$170 million joint venture in 1987, which was China’s biggest overseas investment at the time.

Ambrose said cooperation between the two countries represented China’s “commitment to sourcing a basic strategic raw material from the offshore and marking the end of China’s policy of self-reliance”.

The relationship eventually soured nearly three years ago at the start of 2020 as the previous Morrison administration called for an investigation into the origins of the coronavirus having earlier banned Huawei Technologies Co. from Australia’s 5G network.

The meeting between Albanese and Xi on the sidelines of Group of 20 (G20) in November came after regular and formal top-level interactions between the two governments had been halted for nearly three years.

The previous government consistently portrayed China’s actions as unilateral, unprovoked and inexplicable behaviour from China and completely incorrigible

“The previous government consistently portrayed China’s actions as unilateral, unprovoked and inexplicable behaviour from China and completely incorrigible,” he said.

“How can you have problems solved if you can’t get any ministerial contact?”

China has employed a relatively assertive attitude on diplomacy over the past few years when dealing with its international partners, but Xi also met with a number of foreign leaders at the G20 as a signal to maintain China’s connection with the world.

Ambrose said that Xi’s remarks at the G20 were an “encouragement” to move the relationship with Australia forward instead of just simply stabilising and restoring ties.

Australia must ‘entrench’ role as China’s key supplier after trade bans ‘fail’

“I think Foreign Minister Penny Wong has been a quiet and persistent pioneer in detaching ourselves from the old formulations, but knowing that she could only change those attitudes and the language slowly and gradually to make it more balanced and moderate,” Ambrose said.

High-technology development and building innovation are key focuses for China, but it needs foreign investors to help advance the economy.

Ambrose, though, thinks that there is a “wait-and-see” moment because foreign investors will in general be more cautious before putting money into China amid current uncertainties.