Taiwan wants to be bilingual by 2030, lifting English proficiency to take ‘another step’ to aid economy

- Taiwan has rolled out a plan for NT$30 billion (US$982 million) of spending until 2027 to help meet its goal of increasing English proficiency by 2030

- It is out to compete with Hong Kong, Singapore, India and the Philippines where English is used in the government and by the legal, professional and business sectors

David Feng, a 23-year-old bilingual student, embodies where government officials want Taiwan to be by 2030 to help boost the island’s competitiveness internationally.

Feng can communicate fluidly with foreigners, enjoys smooth travels overseas and can read information that would be off limits to a large number of his compatriots.

“A bundle of valuable information uses English as the primary language, which allowed me to cultivate some specific knowledge vaguely known in Taiwan,” said Feng, who will pursue a master’s degree in Asian studies at George Washington University in the US capital later this year.

Taiwan announced its plan to increase English proficiency in 2018 and in March rolled out a plan for NT$30 billion (US$982 million) of spending over the next five years, as well as specific targets for compulsory education as it seeks to compete with the likes of Hong Kong, Singapore, India and the Philippines.

We believe it will help to improve Taiwan’s attractiveness and competitiveness as an investment destination

A boost in English in Taiwan, where Chinese is the official language, is expected to help domestic companies seek more business overseas, while also making the island more attractive to investors and tourists.

If government regulations, policies, tenders and websites can be found in “legally binding English”, foreign businesses could save the trouble of translating documents into Chinese, said Freddie Hoeglund, chief executive officer of the European Chamber of Commerce in Taiwan.

“The [chamber] welcomes the government’s goal of becoming a bilingual nation as we believe it will help to improve Taiwan’s attractiveness and competitiveness as an investment destination,” Hoeglund added.

Hong Kong is already officially bilingual, with both Chinese and English widely used in the government and by the legal, professional and business sectors.

English proficiency already affects the ways people “compete in the international market” and how companies screen for new hires with sufficient language skills to “convey what the company is doing” to outsiders, said National Taiwan University journalism graduate student Luo Ssu-han.

“The government’s promotion of a bilingual policy is to prepare local people with an international level of English and raise by another step the competitiveness of Taiwanese talent and enterprises,” Taiwan’s cabinet said in a statement last month.

As components of the 2030 plan, 210 of the schools in Taipei should be bilingual by 2026 and all schools in New Taipei City – the island’s largest municipality – will have a full English-plus-Chinese curriculum by 2030.

Smaller cities have also been set goals for numbers of schools that should be equipped to operate in both languages within the next seven years.

The government has not mentioned translating official documents into English or using it as a legal language in venues such as courts or parliament, but it has called for raising the levels within the civil service.

The government’s elevation of English could inspire more people to study it, according to Thitinan Pongsudhirak, director of the Institute of Security and International Studies and associate professor of the International Political Economy within the Faculty of Political Science at Chulalongkorn University.

Thailand’s Ministry of Education set out a plan in 2016 to equip all primary schoolchildren with sufficient English by 2026 to handle everyday situations.

[An official second-language effort] could really open the gates to learning, self learning, and spillover effects for all kinds

An official second-language effort in Thailand or Taiwan “could really open the gates to learning, self learning, and spillover effects for all kinds,” Thitinan added.

Taiwanese people typically study English formally from as early as seven, but students often complain that teachers focus on preparation to pass written exams rather than fluency in speech or for the writing of documents.

A focus on reading and listening gives students enough English to pass classes, but leaves many afraid of speaking in public, Luo added.

Private so-called cram schools for English – used to train students to achieve particular goals – cost between NT$70,000 (US$2,293) to NT$130,000 per semester, which is sometimes tough for middle-class families to afford.

Most of the population in Taiwan doesn’t even speak English, and students who learn the language lack the environment to practise with their family or friends

Jason Hou, vice-president of the Kojen English Centres network of 27 private schools in Taiwan, said students normally reach a “set level” of proficiency by ages 13 to 15 with an aptitude for speaking – something not every peer in Asia is so able to attain.

Hou places Taiwan “in the middle” among regions in Asia, below the level of English of Hong Kong, Singapore or India, but ahead of most other places.

Feng finds that most standard English courses in Taiwan “focus on exams and specific questions” rather than everyday use and overall ability.

“What’s worse is that most of the population in Taiwan doesn’t even speak English, and students who learn the language lack the environment to practise with their family or friends,” he said.

Taiwan’s 2030 plan also covers English in higher education and through digital learning.

Taiwan’s next generation will be equipped with better international competitiveness by adding bilingual capabilities to their professional expertise

“Taiwan’s next generation will be equipped with better international competitiveness by adding bilingual capabilities to their professional expertise,” the government’s National Development Council said.

Last year, mainland China finished behind the likes of Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia and Philippines in global rankings for English proficiency.

The 2022 English Proficiency Index by EF Education First ranked China at 62, a “low proficiency” nation, down from a “moderate” ranking of 49 in 2021. The index does not cover Taiwan.

Singapore retained English as its main language after its independence in 1965 as a way to seek economic prosperity.

The Philippines learned and retained English due to the use of the language in schools dating back to the US colonisation of the archipelago through the mid 1900s.

Most signs in the Philippines appear in English, and even in remote rural areas, it is understood, offering a boost to the tourism sector.

English in India, also a former British colony, is seen to endure largely as a way to ensure communication among states where populations do not speak Hindi.

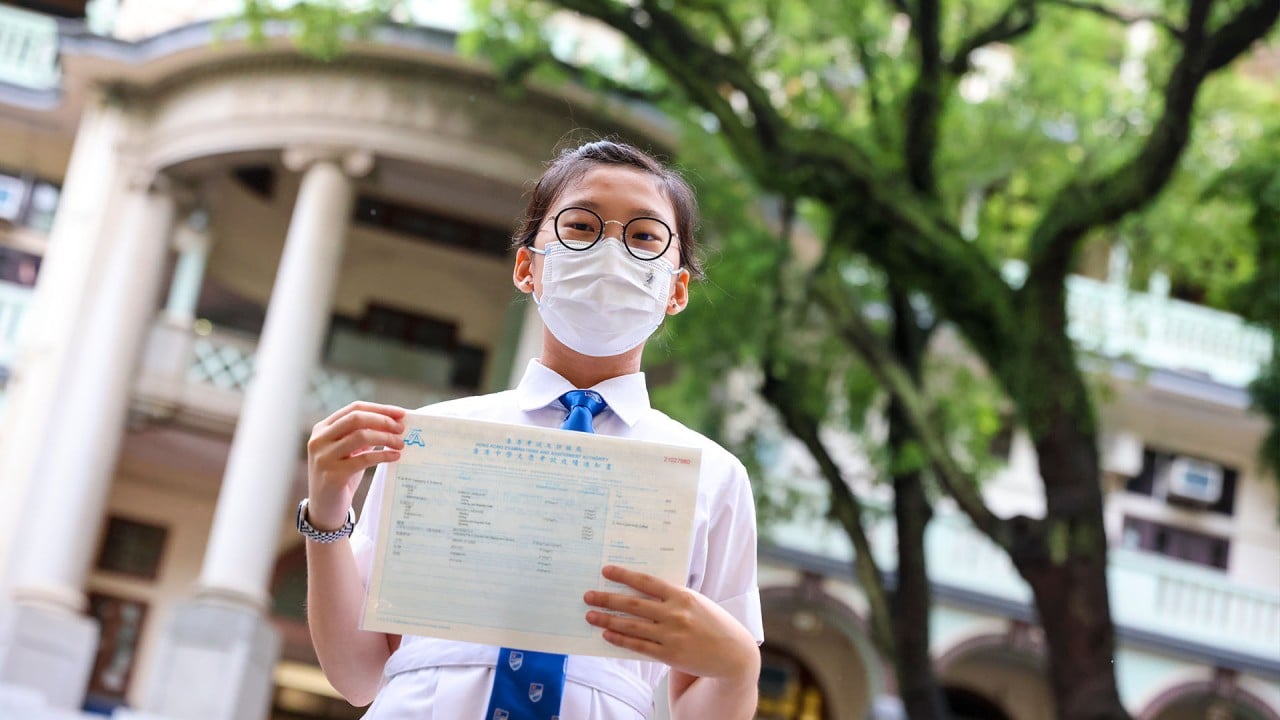

And in Hong Kong, the Education Bureau requires students in government-run schools to be able to write in both Chinese and English and speak English, Cantonese and Mandarin.

Hong Kong’s 29-year-old Language Fund added HK$5 billion (US$636 million) in seed money in 2014 for the long-term development of language education.

The number of students in Hong Kong achieving the level of English required to study at a local university via the Diploma of Secondary Education – which is administered at the completion of a three-year senior secondary education – increased from 50.1 per cent in 2012 to 53.2 per cent in 2022.

In last year’s world competitiveness rankings released by the International Institute for Management Development, which considers language education as one of its criteria, Singapore was behind just Denmark and Switzerland at the top of the rankings, with Hong Kong fifth.