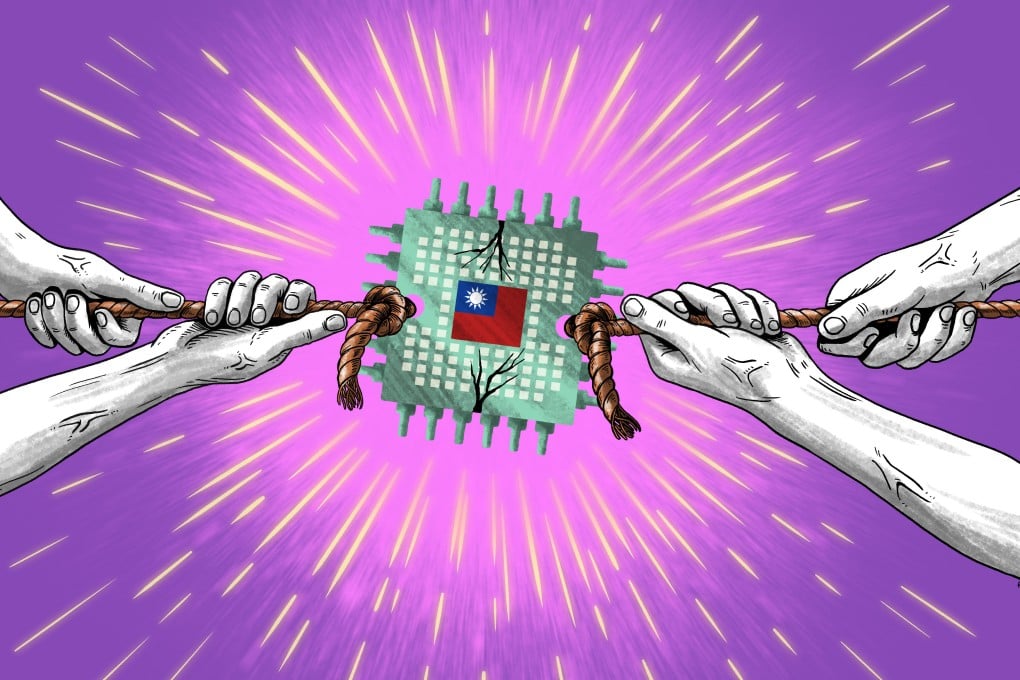

Taiwan’s prized semiconductors not unbreakable ‘silicon shield’ they once were as mainland China, West develop own bargaining chips

- Cross-Strait tensions are said to be chipping away at Taiwan’s long-held dominance in the hi-tech industry where onshoring and reshoring efforts are becoming commonplace

- Threat of conflict with mainland China and sanctions from the West have industry on edge, underpinning a rapid diversification of semiconductor supply chains

A sharp decline in Taiwan’s ties with mainland China could extend to the very devices being used to transmit and read this story.

The far-reaching implications from what has been a geopolitical tug of war are ultimately likely to bolster mainland China’s standing as a dominant supplier of older-model semiconductors while ramping up the need for Western allies to rely more on themselves for cutting-edge chips – a scenario that industry insiders say threatens to erode Taiwan’s formidable “silicon shield” that has long afforded the island a privileged position in the global supply chain.

The island’s continued production of nine in 10 of the world’s advanced chips at factories is unmatched anywhere, and it helped earn Taiwan that defensible sobriquet around the turn of the century.

But in recent years, mainland China has invested heavily to move up the value chain for critically important chips that power everything from cellphones and other consumer devices to electric cars and applications for AI and quantum computing.

And now, mounting tensions across the Taiwan Strait – which intensified following the inauguration of William Lai on Monday as Taiwan’s leader – are pushing the West to diversify advanced chips away from Taiwan and to their own homelands in case any cross-Strait conflict threatens to end the island’s economic advantages.

Lai represents a Taiwanese political party that is cold to mainland China. He said in his inauguration speech that mainland China’s effort to “swallow up” Taiwan would “not disappear” until the island gave in.

The fate of Taiwan’s ‘silicon shield’ is uncertain as economic interdependence encounters obstacles