Hongkongers’ prejudices persist even as mainland Chinese migrants become better educated, speak Cantonese and English, and hold good jobs

- Nasty stereotypes create a hostile environment for new immigrants to assimilate, population expert says

- ‘Loss for whole society’ if some in Hong Kong refuse to recognise strengths of mainland arrivals

Xie Qiongling has never forgotten how she waited five years in her native Fujian province, in mainland China, for permission to be with her husband in Hong Kong.

A Hong Kong resident, he was working as a waiter at the time. She applied in 1999 to join him under the one-way permit scheme introduced by China in the early 1980s to allow mainlanders to move to the city, mainly to reunite with family members.

The approval from the mainland authorities only arrived in 2004. After she moved to Hong Kong, the couple lived in a subdivided flat in Sham Shui Po.

“I could speak basic Cantonese, but my accent was an issue. People at the market liked to mock my accent. Some would just ignore me, saying they did not understand what I said. I knew some called me ‘that mainland woman’ behind my back,” recalled Xie, now 46.

“I did not care what other people said about me. After all, I had settled in Hong Kong and I considered myself a member of the community. I felt I should be a contributor, not a troublemaker.”

The couple have two children, a son, now 22, and a daughter, 14, who were born in Hong Kong.

Xie found part-time work as a restaurant cleaner and office janitor to help support the family, and did not think they should rely on public help.

She also attended classes organised by welfare groups in her neighbourhood to improve her Cantonese and brush up on Hong Kong culture.

The family now lives in a public housing flat in Kwun Tong. Xie’s son is graduating from university this year, and her daughter is in Form Two.

“In Hong Kong, as long as you work hard, your effort will pay off, unless you choose to give up,” she said.

Since 1995, authorities across the border have allowed up to 150 mainlanders a day to move to Hong Kong.

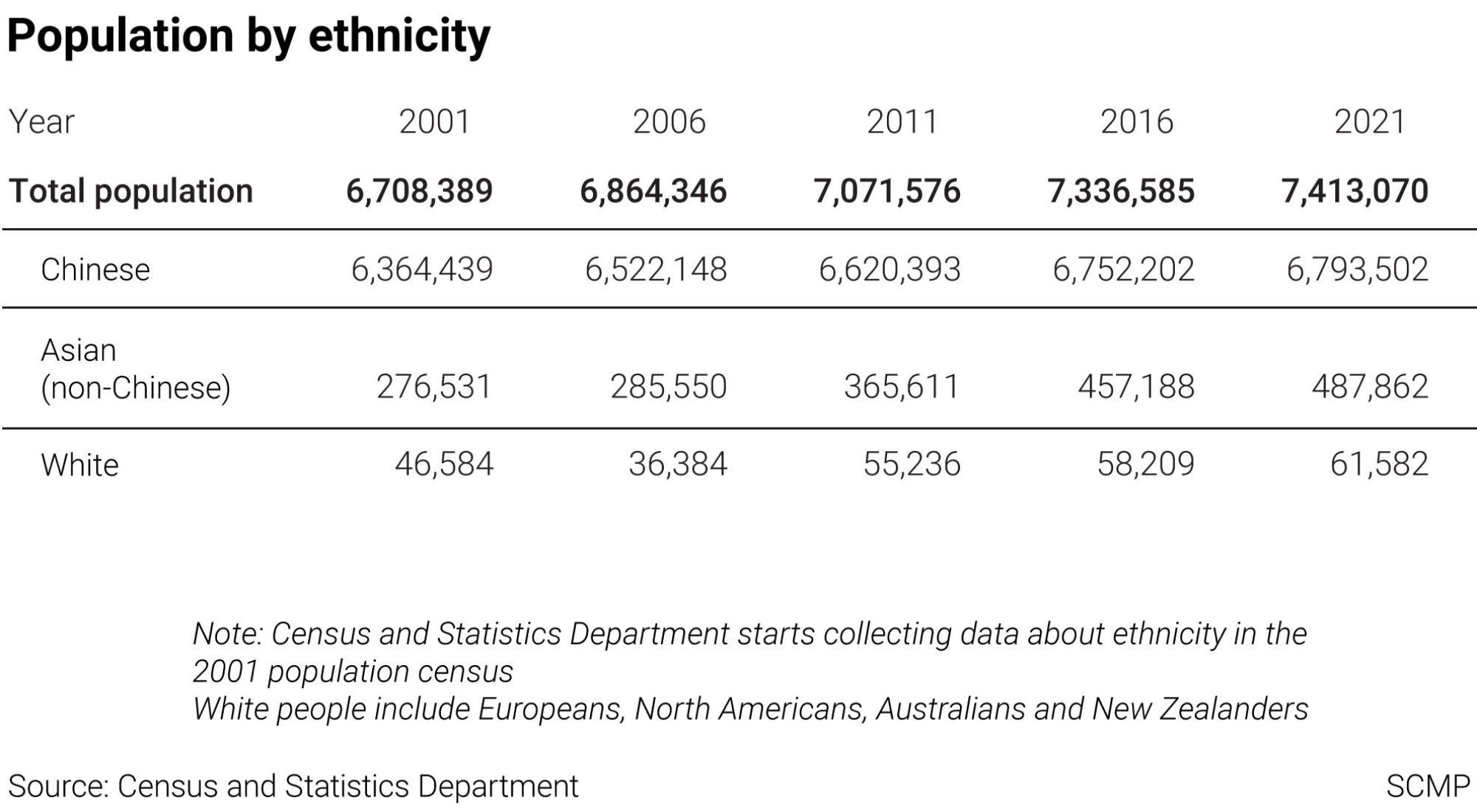

As of the end of last year, about 1.1 million mainlanders had settled in Hong Kong under the scheme since the city returned to China in 1997, official data shows.

The number of arrivals fluctuated over the first decade, reaching a post-handover peak of 57,530 in 2000 before falling to 33,865 in 2007. The number rose again to 57,387 in 2016 before falling steadily to 46,971 in 2017, 42,331 in 2018, and 39,060 in 2019.

Because of the Covid-19 pandemic, only 10,134 arrived in 2020 and 17,900 last year.

At different times over the years, mainland arrivals have been made to feel unwelcome in Hong Kong.

“Migrants coming via the one-way permit system have been stereotyped in many ways – they are thought to be uneducated, lazy, and unable to speak Cantonese,” said Professor Paul Yip Siu-fai, an expert in population studies at the University of Hong Kong’s faculty of social sciences.

“Some people wrongly think they are big consumers of welfare, without being aware that the vast majority of these stereotypes are just plain inaccurate.”

Although those arriving on one-way permits have become better educated over the decades, with more speaking Cantonese and English and holding jobs, old prejudices persist.

“These stereotypes create a hostile environment for new migrants to assimilate,” Yip said.

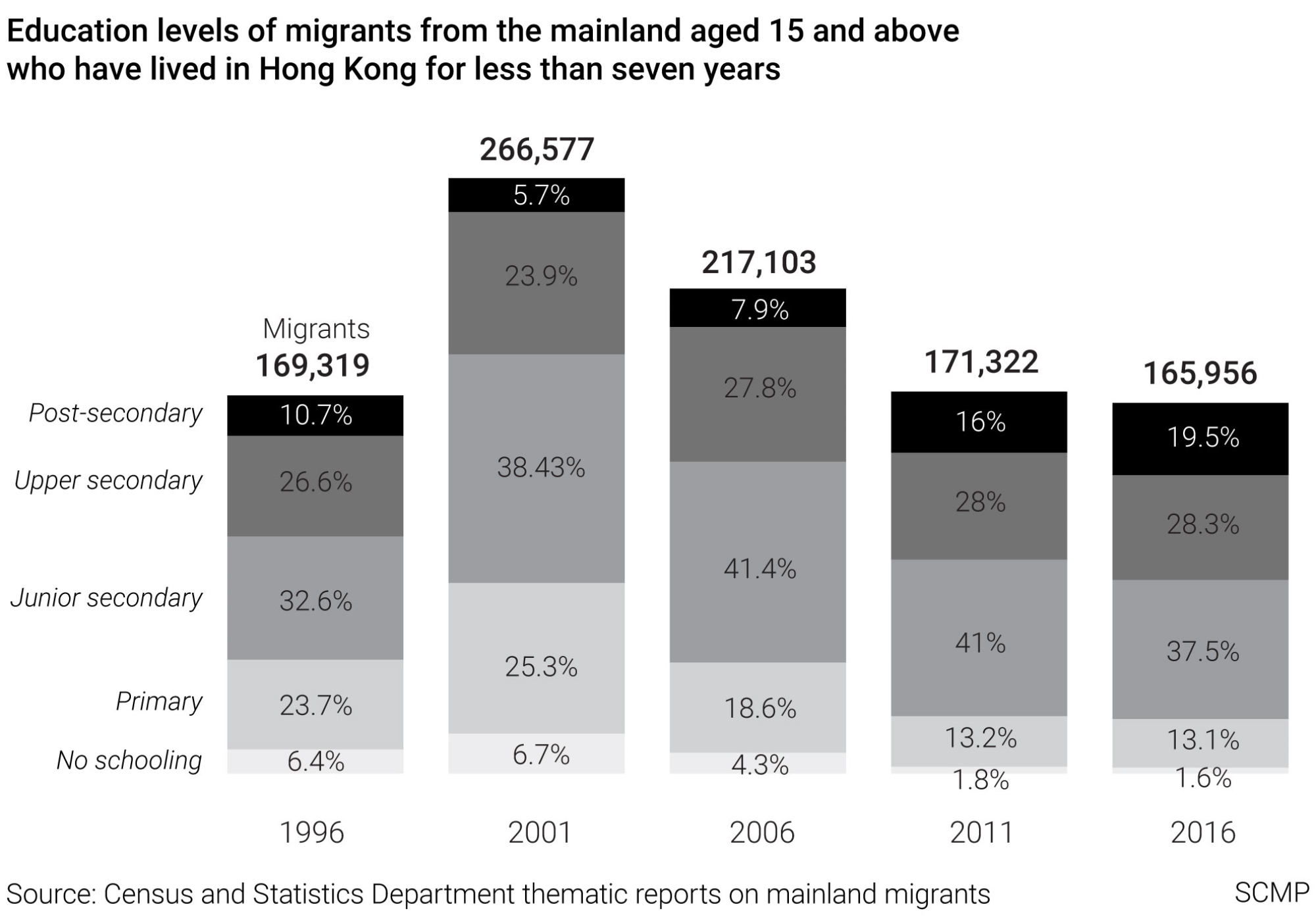

About 25.3 per cent of mainland migrants in 2001 were educated up to primary level at most. This figure fell to 13.1 per cent in 2016, according to the most recent official data available.

Meanwhile, the number with postsecondary qualifications rose from only 5.7 per cent in 2001 to 19.5 per cent in 2016.

In terms of the languages they could speak, almost all mainland migrants – about 95 per cent – could speak Cantonese, while those able to speak English rose from 13.9 per cent in 2001 to 35.9 per cent in 2016.

The labour force participation rate for new migrants also rose from 44.2 per cent in 2001 to 54.2 per cent in 2016. But, like in many other places, new arrivals tended to take up less skilled jobs.

In 2001, more than a third of new migrants worked in “elementary occupations”, according to Census and Statistics Department figures. That referred to jobs such as street vendors, cleaners, messengers, freight handlers, and construction and other labourers.

Only 3.9 per cent were “managers and administrators” or “professionals”.

A gradual upwards shift occurred in recent years, with the proportion in “elementary occupations” falling to 30 per cent in 2016, while those working as “managers and administrators” or “professionals” rose to 8 per cent.

Mainland Chinese immigrants suffer deep-rooted discrimination in Hong Kong

Baptist University sociologist Adam Cheung Ka-lok said it was a loss all round when some in Hong Kong did not recognise the migrants’ strengths.

“The failure of some employers to recognise the new migrants’ work experience or qualifications leads to underpayment, if not unemployment, and that, coupled with the high living cost here could lead to a status downgrade,” he said. “This is not just a problem for the migrants, but for the whole society.”

A study released last year by the Society for Community Organisation (SoCO), an NGO advocating for the rights of mainland migrants and the underprivileged, found that nearly half the 531 new migrants polled said they had experienced some form of discrimination as immigrants.

Some said they had been ignored or ridiculed while shopping or eating out, or discriminated against by employers, colleagues or schoolmates.

SoCO deputy director Sze Lai-shan attributed that state of affairs in Hong Kong to the rise of anti-mainland sentiment and “localism”, or an identity-driven movement, over the past decade.

“New migrants became scapegoats for social problems that the government failed to solve,” Sze said. “Some claimed the new migrants used up the city’s resources.”

In the early 2010s, mainlanders were dubbed “locusts” by those who felt they were gobbling up the city’s scarce resources, and there were “anti-locust” protests led by some localist activists and lawmakers.

The anti-mainland sentiment was first triggered largely by an influx of visitors and women who came from across the border to give birth in Hong Kong, mainly for their children to have the right of abode and access to social services in the city.

In 2003, after Hong Kong’s economy was devastated by the Sars health crisis, mainland authorities allowed residents of major cities to visit Hong Kong on an individual basis. Before that, they could only visit in group tours or on business visas.

Some mainland women took advantage of the relaxed rule to have their babies in Hong Kong.

The number of babies born to non-local parents leapt from only 620 in 2001 to 16,044 in 2006 and kept rising to a record 35,736 in 2011, or about 37 per cent of all births. This resulted in overcrowding of maternity wards at local hospitals.

To allay Hongkongers’ concerns, then leader Leung Chun-ying banned mainland women from scheduling births in the city’s hospitals from 2013.

That year, former localist lawmakers Gary Fan Kwok-wai and Claudia Mo Man-ching and other activists took out advertisements in newspapers, demanding the government cut the number of new migrants, saying Hong Kong could not afford to take in more people.

Coincidentally, the city’s top court, the Court of Final Appeal, decided in 2013 that a government rule requiring new migrants to be resident for seven years before they became eligible for social welfare benefits was unconstitutional.

The government was forced to reinstate its previous policy of a one-year residence before new migrants could apply for Comprehensive Social Security Assistance (CSSA).

Unwelcome mat: Hong Kong’s loss if mainland Chinese leave

“The ruling somehow reinforced the stereotype about new migrants being here to abuse social welfare benefits, although it was not supported by facts,” said Sze, whose group backed the migrants in that legal battle.

At the end of 1999, 23,140 CSSA cases involved new migrant recipients, or about 10 per cent of the total, according to official data.

That rose to 41,571, or 14 per cent of the total, in 2004 before falling steadily to 17,921 (6.2 per cent) in 2009 and 9,540 (3.7 per cent) in 2013.

After the court ruling, the number of CSSA cases involving new migrants rose to 13,551 in 2014, or about 5.4 per cent of the total. It declined after that, with 10,709 cases (4.7 per cent) in 2020.

The government’s annual poverty situation reports also suggest that migrants are not a major source of the city’s deprivation problem.

In 2009, there were about 37,800 new arrival poor households, or 7 per cent of the city’s overall poor households. That declined over the years to 21,900 in 2020, or 3.1 per cent of the total.

The government defines new arrival poor households as those with at least one member who is a one-way permit holder and has lived in Hong Kong for less than seven years, with a household income less than half the median by household size.

Noting the facts did not back up the criticisms of the newcomers, Sze said: “Migrants lack a collective voice. Academics can perhaps play a role in collecting and using accurate, objective data to help win over xenophobes.”

She said there was a tendency for people to leap to conclusions that because there were more migrants, some locals would lose out or make less money in the competition for jobs.

“But migrants also increase the population size and the size of the economy,” she added. “If migrants grab jobs from locals, then school-leavers entering the job market also do so. If this logic holds, Hong Kong’s economy should have been much better off when its population was only 4 million [in the 1970s].”

Over the years, anti-mainland sentiment became a political rallying call for activists.

It shifted focus, from mainlanders giving birth in the city to targeting visitors from across the border as their numbers surged over the years to reach 51 million in 2018, out of a record 65.1 million arrivals.

Localist activists said they snapped up goods, flooded the streets and were a nuisance.

Debate about mainland migrants and the pressure on public services heated up again in 2019 after some local doctors claimed the one-way permit scheme was a source of overcrowding at hospitals. They claimed many mainlanders visited public hospitals for services after they arrived on one-way permits.

Baptist University’s Adam Cheung said China’s rise in recent years also contributed to the conflicts between locals and mainland migrants.

“In the past, new migrants had to learn to speak Cantonese if they were to assimilate into Hong Kong society because Hong Kong culture was regarded as superior,” he said.

“But in recent years, with the rise of mainland China, mainland culture is becoming more influential. Some new mainland migrants do not necessarily need to learn to speak Cantonese. They can simply use Mandarin and many Hongkongers can also understand them.

“As such, the mainlanders are becoming more visible and Hongkongers are more aware of their presence.”

Professor Eric Fong Wai-ching, an expert in migration and urban sociology at the University of Hong Kong, agreed that the socio-economic status of mainland migrants had risen in recent years.

He noted that the decline in Hong Kong’s birth rate posed a greater problem than the influx of mainlanders and, in fact, the city had to come up with policies to attract and retain talent.

“As new migrants get more educated, they are also more mobile. They have more choices,” said Fong, head of the university’s sociology department. “If they cannot find satisfaction here, they will go somewhere else to find it. That is going to be a challenge for Hong Kong as all countries are now competing for high quality migrants.”

The number of live births in Hong Kong dropped steadily from 59,300 in 1997 to about 47,000 in 2003.

It rebounded to 95,000 in 2011 mainly because of mainland women having their babies in the city, but began declining again after the government banned them from coming to give birth. Total births sank to a low of 37,000 last year, according to official data.

Since 2020, Hong Kong has recorded more deaths than births and the population shrank 0.4 per cent that year and 0.9 per cent in 2021.

Research on new migrants commissioned by SoCO last year found that many better educated migrants did not stay long in Hong Kong.

Among male migrants who arrived from 1997 to 2001, 28.2 per cent held a bachelor’s or more advanced degree in 2001. Their percentage almost halved, to 14.6 per cent within five years, and continued to fall in later years.

Hong Kong legislator Gary Zhang Xinyu is less pessimistic. He grew up in Shenzhen and came to Hong Kong to attend university, then stayed on and became a permanent resident.

“People come and go. What’s most important is to maintain the attractiveness of Hong Kong to mainland or overseas talent,” he said.

“Many overseas students study at Harvard University and many of them will return to their home countries after graduation. We have never heard Harvard complain that they are helping other countries train talent. Instead, Harvard is very proud that the university can attract so many talented students from across the world.”

Agreeing, SoCO’s Sze said Hong Kong needed to build a “discrimination-free, migrant-friendly” environment.

Nearly two decades after arriving, Xie Qiongling, who fought discrimination to raise her family in Hong Kong, said: “Even today, I do not feel I am 100 per cent a Hongkonger.

“Many locals do not see new migrants as people coming to start new lives. They still regard us as outsiders, even though we also have Hong Kong ID cards.”