More Hong Kong heritage being saved, but critics question uses it’s being put to

The government has taken a less passive approach to preserving old buildings, but legal and financial hurdles to saving heritage remain, and then there’s the issue of what to use the buildings for

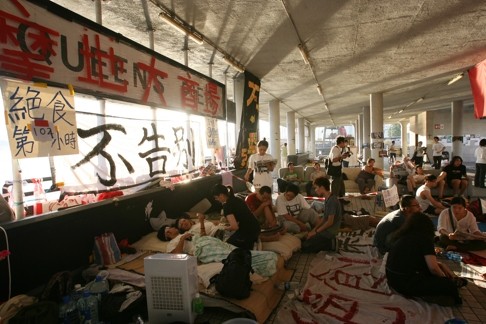

Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor, then Secretary for Development, responded to the fact that young people chaining themselves to the pier were obviously desperate to inherit some pieces of old Hong Kong. The Commissioner for Heritage’s Office was set up the following year; new infrastructure projects would have to assess their impact on heritage; and non-profit organisations have moved into vacated government properties under the Revitalising Historic Buildings Through Partnership Scheme or, simply, the Revitalisation scheme.

SEE ALSO: The different fates of two heritage buildings Hong Kong government saved

The legal and financial challenges in saving older buildings are daunting, and sometimes insurmountable. The government failed to save Ho Tung Gardens, built in 1927 by Sir Robert Hotung. Hotung’s granddaughter Ho Ming-kwan had asked to be paid HK$7 billion to keep it out of developers’ hands, a sum that the government deemed too high. The main building was demolished for development in 2013 and Ho sold the site in 2015 for HK$5.1 billion.

These are issues that have been in the news a lot recently. Carrick, the 128-year-old European-style mansion at 23 Coombe Road, has been taken over by the government for preservation after it cut a controversial land exchange deal with the owner, a Li Ka-shing-controlled company. A new batch of properties under the Revitalisation scheme have been earmarked for unconventional uses and are still awaiting approval from the Legislative Council after the Public Works Subcommittee gave the initial green light.

Each property has its own sensitivities: the plan to transform the former Fanling Magistracy into a youth leadership training centre has been criticised for being either too commercial or a potential political tool. The long-term financial sustainability of a news museum planned for the Bridges Street Market has been questioned. As for plans to make Haw Par Mansion into a music school, concerns have been raised over public accessibility and the fact that the school is linked to Sally Aw Sian, the original owner who sold the site to Cheung Kong Holdings for redevelopment in the first place.

Yam says he is glad that his office managed to convince the Lands Department and the Town Planning Board to recategorise a piece of green belt land opposite Carrick to “residential use”, making it an acceptable alternative site for development to Juli May, the company that was going to tear down the historic building.

“With our assistance and support the developer was able to get approval from the Town Planning Board to rezone a plot of land [and save] this grade one historic building,” he says.

Concern groups wanted the Town Planning Board to reject the application, saying the rezoning of a green belt site for development is detrimental to the environment and against public interest.

“Local residents are not opposing this because they are anti-development, but the government needs to strike a balance. I will continue to oppose this,” says Joseph Chan Ho-lim, the Liberal Party district councillor for the Peak constituency.

There is also concern over how the building will be used following the furore over 27 Lugard Road, another beautiful Peak mansion. Residents and hikers objected to plans to turn it into a boutique hotel, which would have created more traffic in the area.

Unlike 27 Lugard Road, there is public parking by the playground next to Carrick and a minibus drop-off point within easy walking distance, making it relatively accessible.

Now in its seventh year, the Revitalisation scheme has allocated properties to 15 NGOs that have come up with satisfactory proposals. Seven of those are in operation.

The uses that these have been put to arevaried. Lui Seng Chun, a former home of the Lui family, is now the Hong Kong Baptist University Chinese Medicine and Healthcare Centre. The former North Kowloon Magistracy has become the campus of the Savannah College of Art and Design. Mei Ho House, one of Hong Kong’s oldest public housing blocks, has been transformed into a swish youth hostel. None of them resembles a museum.

Yam says the government’s old way of preserving buildings was “too passive”. By turning Kom Tong Hall (formerly owned by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) and Flagstaff House into the Sun Yat-sen Museum and Museum of Tea Ware respectively, the buildings are simply museums displaying artefacts, he says, rather than being reused actively by the community.

Now, the government is asking local NGOs to come up with more “organic” ways to use the buildings, he adds.

“First and foremost, my aim is to turn historic buildings into good, adaptive reuse. It just so happens that such a great proposal came up.” The government is going to let News Expo display anything it wants “as long as it’s legal”, he says. “We really don’t want to micro-manage.”

Yam also says he is not familiar with the details of the revitalised Central Police Station on Hollywood Road – due to open late next year – because the government has handed running of the ambitious project to the Hong Kong Jockey Club.

This model of outsourcing has its advantages. For example, a government-run news museum would certainly go against the basic tenets of an independent press. But it also means that there are different degrees of accessibility to these tax-funded, publicly owned properties, as well as different visitor experiences.

“To assess whether a heritage revitalisation project succeeds or not, we can look at whether the social agenda behind it is fulfilled. A very bad example is the Sun Yat-sen Museum located in Kom Tong Hall,” Lee says.

The museum has been criticised ever since it opened in 2006 for being a waste of space. The number of visitors last year fell 4.3 per cent to just over 60,000, much lower than the more than 200,000 people who went to the tea museum. Lee says Sun Yat-sen is simply a bad subject matter.

“Linking Sun Yat-sen to the building was far-fetched. They say Sun and the first owner studied in the same school, but they studied in different periods. A much better option would have been Bruce Lee, whose mother was one of the owner’s wives,” he says.

Finding the right use for buildings is not easy. The government has more or less given up on the idea of finding a charity to run King Yin Lei (see sidebar). But Lau Kwok-wai, executive director of The Conservancy Association Centre for Heritage, says Hong Kong people should give the scheme more time to prove itself.

“It’s too early to tell whether the Revitalisation scheme is the right way of approaching Hong Kong’s preservation efforts. “There aren’t many properties open yet and they are all in their early days. We will need to wait a few more years before we discover whether they are sustainable.”